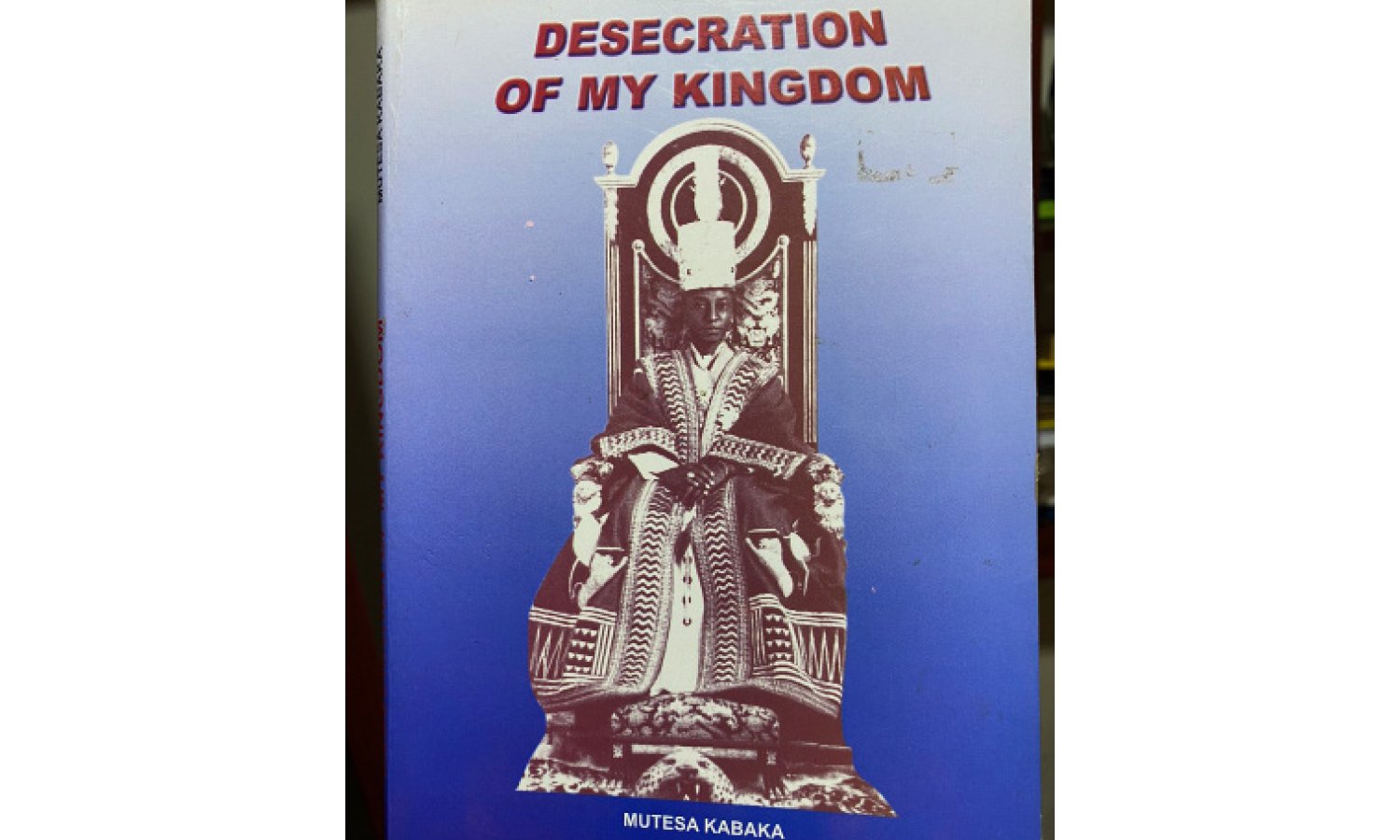

Book Review: Buganda’s darkest hour recollected by its victim

What you need to know:

- Book title: Desecration of My Kingdom

- Author: Sir Edward Mutesa

- Where: Amazon

According to popular literature and film, “Reverse chronology is a narrative structure and method of storytelling whereby the plot is revealed in reverse order. In a story employing this technique, the first scene shown is actually the conclusion to the plot.”

Gandhi, the 1982 epic biographical film based on the life of Mahatma Gandhi, follows this narrative type. The film begins with Gandhi, played by British actor Sir Ben Kingsley, quietly exclaiming, “Oh, God!”, before he falls dead.

His state funeral is then shown; the procession attended by millions of people from all walks of life, with Edward Murrow, the celebrated American broadcast journalist, saying: “Mahatma Gandhi was not a commander of great armies nor ruler of vast lands. He could boast no scientific achievements or artistic gift. Yet men, governments and dignitaries from all over the world have joined hands today to pay homage to this little brown man in the loincloth who led his country to freedom.”

The same narrative form is used for “Desecration of My Kingdom”, the autobiography of Sir Edward Frederick William David Walugembe Mutebi Luwangula Mutesa II, the thirty-fifth Kabaka of Buganda.

Attacked

In Chapter One, the book begins with May 24, 1966, the date of the attack on the Lubiri by soldiers loyal to Milton Obote. It is not raining but pouring, pandemonium has taken root as Mutesa’s party Kabaka Yeka’s misalliance with Milton Obote’s Uganda People’s Congress has gone to seed.

So Mutesa must decamp, in pain of death. Part of his escape route takes him to Bujumbura, Burundi, hitchhiking with two confederates. They are nothing but “vagabonds” when received by the Burundian royal family. In a tragic turn of events, that same year King Ntare V Ndizeye was deposed by Prime Minister and Chief of Staff, Colonel Michel Micombero, who abolished the monarchy and declared a republic following the November coup d’état.

At any rate, a cabinet meeting is held by the Burundi government and it is decided that Kabaka Mutesa must be helped to reach London.

He has lunch with the British ambassador, “surviving the meal only by constant doses of gin and tonic, which doubtless made a bad impression, I staggered back to the house where I was staying.”

Absolute monarch

In Chapter Two, the book takes us back in time to when Mutesa I, the 30th Kabaka, first encountered the British.

“In 1862, [the Baganda] were the most advanced people south of the Sahara,” Mutesa writes before telling us how the Kabaka personified the Baganda and, indeed, Buganda.

The structure of government lent itself to the shape of a pyramid, with the commoners at the base. The saza chiefs were civil servants who attended the Kabaka’s court frequently and were ex-officio members of the Lukiiko or Buganda’s parliament.

Mwanga revisited

In Chapter Three, Mutesa II attempts something of an apologia when examining the Kabakaship of Danieri Basammula-Ekkere Mwanga II Mukasa, the 31st Kabaka of Buganda who ruled from 1884 until 1888 and from 1889 until 1897.

Mwanga is likened by some to Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the notorious Roman emperor who fiddled when the great fire of Rome broke out and destroyed much of the city on July 18 in the year 64. However, Mutesa II is more sympathetic, casting Mwanga as a victim of circumstance.

Meeting Nyerere

After that impasse was resolved in 1955, he writes about his journey home: “On the way, we met Julius Nyerere, who had been inconspicuously at Makerere with me. I asked him what he was up to, and he replied, ‘I am a political agitator.’”

It is interesting that he used the word “inconspicuously” to describe Nyerere’s time at Makerere.

The story goes that when Nyerere was asked to distinguish between the political ambitions of Ugandans and Tanzanians, he reportedly said: “In Tanzania, when one asks for a leader, people shy away. In Uganda, when one asks for a leader, everybody stands up.”

Thus Nyerere, while at Makerere, might have preferred the backseat in order to accommodate the outsize egos of political Ugandans.

Obote versus Mutesa

Mutesa II saw few redeeming defects in Obote. He casts him as an excellent manipulator who had some legislative ability, but was not respected by his peers. This is in stark contrast with Mutesa II, who was born to be respected.

Obote’s problem with the monarchy, then, was arguably more a product of an inferiority complex in the face of Mutesa II’s superiority complex. Thus, a clash was inevitable.

As you might be aware, Buganda kingdom was effectively a sub-imperialist utensil at the table of colonial rule and this is why its influence on Uganda, as a whole, is marked.

This brings us to Chapter Thirteen, the Allocation of Official Posts in Kigezi, 1908-1930 by Denoon, and how the Bakiga replaced Baganda in supplying a colonial bureaucracy in Kigezi. It is noted in this chapter how a British imperialist, Major Jack, found the Bakiga to be a mixed bag. Some were “truculent and offensive” while others were “mild-mannered, inoffensive people.”

This dual estimation of Bakiga is a big departure from the singular and popular description of Bakiga as truculent and aggressive.