Proper welding training could solve youth unemployment

It takes thorough practical training to master using high-end machinery to weld joints. PHOTOS / ABDUL-NASSER SSEMUGABI.

What you need to know:

- The welding industry across the world faces shortages in skilled labour despite the rising demand for welding products. Yet in Uganda, welding is mostly a resort for the semi-educated, whose brains or funds could not earn them a university degree, writes Abdul-Nasser Ssemugabi.

When Sulaiman Mugejjera had just ventured into 3D metallic metal graphics in 2013, he struggled to convince potential clients on the uniqueness of the new technology and why it cost more compared to conventional graphics.

“Their closest imagination was that of a metallic door, which was not so fancy,” he recalls, painting the narrow view Ugandans have of the welding industry. However, seven years later, after mastering sheet metal welding, Mugejjera is one of the few go-to persons in 3D metal graphics, all thanks to welding.

“Nowadays, clients look for us basing on our works elsewhere,” the young entrepreneur says.

Welding is basically fusing separate pieces of metal together, using intense heat and pressure. But if you contextualise the notion of metal joinery, you appreciate the importance of the profession in this world run by metals. From communication gadgets to transport vehicles and medical equipment to ammunition that guard us; construction equipment and all sorts of machinery, are all works of the welder’s gifted hands.

Without the welder’s input, you cannot have that luxurious jewellery you flaunt or crave; that fancy phone, Bluetooth headsets, laptop. That dream bike or car.

In advanced economies, welders are reaping big from the petroleum exploration industry. According to Grand View Research, a US based market research and consulting company, the global welding products market size was estimated at $ 14.49b in 2019. Factors such as design flexibility, reduction in the overall weight of the building structures, and the ease of modification are projected to promote the demand from construction and industrial application segments.

Yet in Uganda, welding is mostly a resort for the semi-educated, whose brains or funds could not earn them a university degree.

“The jobs are there but the youth have not yet appreciated the skilling agenda. We have got to find ways of marketing and rebranding (Technical Vocation Education and Training) TVET because this is the way to go if you are to get out of poverty. After Senior Six, everyone is thinking about joining the university, and not sure what exactly to do,” said state minister for Higher Education, John Chrysostom Muyingo, last year.

Sector players believe Uganda can also increase its share of the global market, if attitudes are changed to view welding as a vocation richer, more important and more diverse than mere joining of metals. The first step, they say, would be changing the education model.

Ideal model

In developed countries such as the USA, Netherlands, China, Japan, welding technology is a serious vocation with learners graduating from certificates to degrees.

Ronald Ssezibwa, the CEO of Seb Engineering Services, in Gombe, Hoima Road, says even in Uganda it is possible. “But it begins with priority, developing sustainable policies, funding and supervision.”

This is what inspired him to establish Seb Institute Of Welding And Technology (Siwet) to exclusively impart practical and theoretical welding skills to trainees at all levels. According to courseseye.com, there are three colleges and universities offering certificate in welding and fabrication in Uganda: Ntinda, Kiryandongo Technical Institute and Daniel Comboni Vocational Institute in Gulu. But Siwet could be Uganda’s first welding-only institute.

“We the stakeholders know what should be done, and are ready to help in this long road to transformation,” says Ssezibwa, who concurrently studied electrical engineering and computer maintenance at Masaka Technical College after his A-Level at Bishop’s Senior School Mukono.

Most welding courses emphasise safety; knowing how to use the proper personal protective equipment and safety protocols to avert danger and accidents; welding basics; everything about correct power voltages, metals, and consumables; interpreting blueprints and welding symbols; welding processes, to determine the best welding method for the job. What joins bridges is different from what is used to make computer motherboards, among others.

Mugejjera says prioritising welding is a brilliant idea and suggests the Education Ministry should make sure it is accredited by the Welding Institute of Cambridge, UK so that trainees get certified skills recognised all over the world. Doing this means widening the horizon of job opportunities.

Ssezibwa also emphasises the need for a dual training system in which welding and all vocational courses are spearheaded by the respective companies in the trade.

“Government should establish several centres of excellence specialising in several technical skills such as tailoring, welding, carpentry, et al, where learners train practical skills instead of bringing them for internship,” he suggests.

This, Ssezibwa says is the best model of training because it not only helps the trainee learn the skills hands-on, but also exposes the learner to the realities and dynamics of the industry, creates the all-important employer-employee link and enables a cost-sharing relationship between the sector players and the state.

Harriet Kagezi, the principal of Ntinda Vocational Training Institute, says the training system could work but for it to thrive, it would require stakeholder policies to be in place and implemented as highlighted in the 2019 Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Policy, which was benchmarked from developed economies such as United Kingdom, France, Germany and South Korea. She adds that Ntinda VTI will pilot the system from 2021-2023.

Viable venture

TVET programmes are still widely perceived as a preserve for dropouts or under-performing students. But Hon. Muyingo wants this narrative to change because of the role technical and vocational skills play in reducing unemployment among youths.

Welding is still perceived as a male only profession although females too can thrive as already shown by some female trainees that have done the short course at Siwet.

Mugejjera, the 3D metal designer, adds that as much as welding is almost a virgin goldmine, full of opportunities, it is also easy to start as a job.

He says a starter welding machine costs about Shs700,000 and the skills are easy to acquire. “You only need to be innovative to stand out,” he says.

Assortment of careers

The welding industry is a pool of countless job opportunities. Some are identifiable by the names of their specifications; metal fabricator, master jeweller, master plumber, auto body welder, structural iron and steelworker, tool and die maker, pipefitter, oil rig welder and industrial boilermaker, among others.

There are welding inspectors, who ensure that weldments and welding-related activities comply with quality and safety criteria by; verifying that the material is correct and in order, watching weather conditions, monitoring repair work in accordance with procedures, ensuring each weld is marked and identified. According to Salary.com, in the U.S. by May 2021, such professionals made between $49,000 (Shs175m and 234m) $66,000 in salary annually.

Innovations

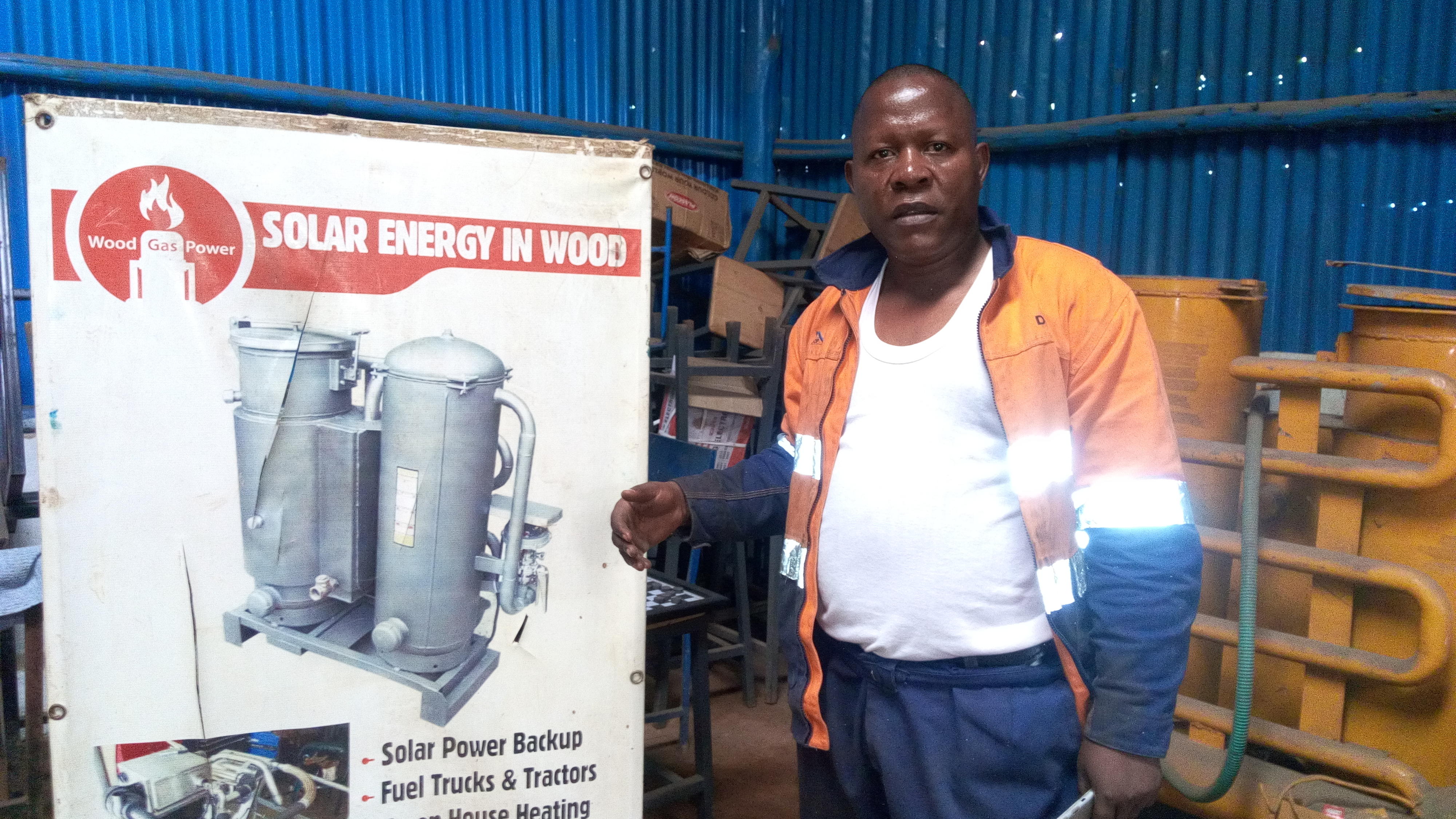

As much as creatives impress us with novel ideas, they also revive old trends. Ssezibwa, whose company manufactures agro-food machinery and farm implements, general construction and engineering equipment, is also developing automated car parking systems.

But he is also joining other technicians in reviving wood gas generators to address the fuel shortage and the overreliance on electricity, charcoal and firewood as the sources of energy.

These generators were popular in the 19th and 20th centuries and especially during the oil shortage after the Second World War.

Challenges

The welding industry across the world faces shortages in skilled labour despite the rising demand for welding products. That partly explains why all students trained at Ntinda and Siwet and most training stations are absorbed in the industry.

However, Kagezi and other trainers find welding a very expensive vocation to train mainly due to expensive materials such as argon gas, stainless steel, aluminium steel, yet parents still despise vocational training and are hesitant to pay the adequate fees.

For instance most course text books cost a lot of money. Basic books such as the Jefferson’s Welding Encyclopedia 18th Edition costs about Shs3m.

The stakeholders hence ask the government to invest more into subsidising the welding sector to make training more affordable and viable .

Kagezi also admits that few girls enroll in welding courses. For example, by June there were only three female welding trainees at Ntinda VTI, in a class of 21.

It is obvious that treating welding as a more serious vocation would create numerous jobs and solve the unemployment burden mostly among Uganda’s majority youth population and promote import substitution in the long-term. But as Ssezibwa asserts, it begins with giving it priority.