Prime

When cricketers put their heads in the firing line

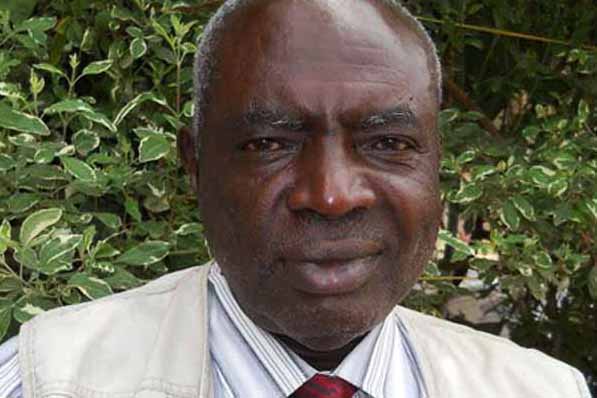

Wanderers captain and batsman Dennis Musali goes for a shot as Suleiman Abdelamid (R) keeps the wickets for Tornado in last year’s 50-over Multiple Industries National League decider. Both players are seen here without any head protective gear. PHOTO BY Eddie Chicco.

What you need to know:

The cricket ball is almost as hard as a stone and can hit someone to death. But some Ugandan batsmen and wicket-keepers continue to play without protective gear. Yet, just last year, a South African player lost an eye during a match

Safety is quite an essential aspect in sport for athletes, officials and fans.

The topsy-turvy matters of security at Sunday’s Boston Marathon bombings are perhaps a gruesome reminder that there will never be 100 per cent safety and security for anyone involved at sports events.

From the Munich massacre at the 1972 Olympics and the Centennial Park bomb at Atlanta 1996 to fan violence at football games, the stabbing of tennis player Monica Seles and attacks on Togo footballers and Sri Lanka cricket players, there is always a limit to what state authorities can do.

Yes, security is just a core element of safety for sport to go on anywhere. Whereas its that much inevitable, some things are out of touch - sportsmen are also always liable to injuries at the expense of earning success while either on track, course, oval, pitch or courts. Some are avoidable and the rest remain part of the package.

Talk of cricket, the gentleman’s sport. There is no much contact like in rugby, basketball or

football but the game can be quite dangerous.

Cricket balls, weighing between 155.9 and 163.0 grams, are known for their hardness and for the risk

of injury involved when using them.

Their danger was a key motivator for the introduction of protective equipment. No wonder batsmen and wicket-keepers wear pads, gloves, glasses, jockstrap, abdomen guards and helmets among others while facing bowlers on the crease. Helmets are very vital for head protection. It’s very rare to see a batsman in international cricket go onto the crease without a helmet. But for some players in Uganda, wearing the head gear seems to be a burden.

“The helmet is kept off for comfort,” opines batsman cum wicket-keeper Lawrence Ssematimba. In most cases, while playing for the national team, Ssematimba squats behind the stumps with a helmet lying just besides him on the ground. He has done this for years despite the risks involved in playing his position without protection. Just last year, Mark Verdon Boucher’s career ended prematurely due to the severity of an eye injury.

The former South African wicket-keeper was not wearing a protective helmet nor glasses when his left eye was struck by the bail after leg-spinner Imran Tahir bowled Somerset’s Gemaal Hussain.

Boucher’s lens, iris and pupil were all damaged and his life has never been the same. Following surgery to the eyeball, Boucher was ruled out of the rest of the tour. Due to the severity of the injury, Boucher—who had planned to retire at the end of the tour—retired from International Cricket on July 10, 2012.

There was no damage to the retina but he had to undergo two operations. With such incidents, it’s a clear message to players that protective gear is a must.

Ssematimba’s elder brother Frank Nsubuga, explains that he knows when to do away with the helmet.

“Of course I keep my helmet off when the bowlers are slow paced,” he tells SCORE. “Other times, I wear it because I would not want to get my eyes injured. Any batsman should always wear the helmet irrespective of the circumstances.”

But irrespective of the bowler’s style whether its slow, pacy or spin, you rarely see Nsubuga walk onto the oval with a helmet.

During last year’s 50-over league, Nsubuga had to nurse a swollen eye after getting hurt by Daniel Ruyange’s delivery. He endured lots of pain and was lucky not to lose the eye. His head was also slightly hurt.

But even after that, Nsubuga usually wears a cap rather than having his head in the cage. And that was much notable during the ICC Africa Division One Twenty20 Championship at Lugogo and Kyambogo ovals in February and even the recently concluded National Twenty20 League.

“We were wearing new helmets (received from India’s Kolkata Knight Riders and Mehta Group) for that tournament,” Uganda’s national team captain Davis Karashani said of the continental tournament. “They were tight. Most guys kept them off for the case of spin bowlers because they feared missing the

ball,” he explained. National team all-rounder Richard Okia only wears the helmet depending on the nature of the wicket in an innings. “If its a slow wicket, I will not wear it,” he says. “I will wear the helmet If I am going to face spinners or if the deliveries are bouncing,” Okia notes.

But things seem different when bowling. A bowler always ensures he puts up the toughest conditions for any batsman without a helmet.

“The bowler will come hard at the batsman (without headgear). He will bowl clinically and force you to wear the helmet,” Okia adds.

Kenyan legend Steve Tikolo, who has been Uganda’s batting coach for one year, says it’s difficult to ‘force’ players to protect their bodies. “Whatever the players decide to do with their gear while on the oval is their decision which I cannot influence,” Tikolo says.

“But If a tournament or particular game has no fast-paced bowlers, then there is no threat,” Tikolo, a former Kenyan batsman - the first player outside Test playing nations to cap 100 (One Day Internationals) ODIs, adds.

Nonetheless, other national team batsmen like Deus Muhumuza, veteran Benjamin Musoke and Arthur Kyobe, all Tornado players, stick to the basics and keep the gear on while at the fulcrum.

“I need to have guaranteed protection,” Kyobe says. “I do not want to keep risking.” Kyobe is often hit by balls especially against left-arm bowler Charles Waiswa while practicing in the nets at Lugogo.

Cricketers known to have died as a result of on-field injuries after being hit while batting include George Summers of Nottinghamshire (hit on the head by the ball at Lord’s in 1870), Karachi wicket-keeper Abdul Aziz (hit just above the heart in the 1958-59 Quaid-e-Azam Trophy final), and Ian Folley of Lancashire (knocked by the ball in the face in 1993). In 1998, Indian Raman Lamba died when a cricket ball hit his head in a club match in Dhaka.

Lamba was fielding at forward short-leg without wearing a helmet when a ball struck by batsman Mehrab Hossain hit him hard on the head and rebounded to wicket-keeper Khaled Mashud.

Four years ago, a cricket umpire died in South Wales after being hit on the head by a ball thrown by a fielder.

If a flying six can injure a fan in the stands far away from action on the oval, then what of the batsman or wicket-keeper who are the first recipients of deliveries from a bowler? Fortunately, such accidents have not happened in Uganda but its important to take caution.