Prime

1980 General Election: The controversies, highs and lows

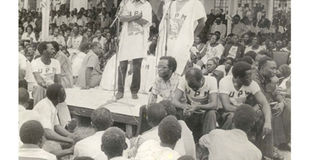

Museveni addresses a rally in Mbale in 1980. Besides using the 1957 electoral law, there were a number of flaws in the process that forced a UPM candidate, Mr Bakulu Mpagi Wamala, to go to court. FILE PHOTO

What you need to know:

- The 1980 general elections were filled with a number of twists and turns that nearly derailed the election.

- The committee recommended a total of 146 constituencies, and one ballot box instead of a box for each party, with all candidates on the same ballot paper, and votes to be counted at the polling station after voting. Party agents were to be present at each polling station.

The post-Idi Amin 1980 general election was hoped to reset the country on a democratic path. It had been mapped out during the Moshi Conference in Tanzania, convened by Ugandan exiles, forced out by the misrule under Amin.

Then President Godfrey Binaisa is quoted to have pushed for a no-party election under the umbrella Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF).

“Binaisa too had repeatedly insisted that no-party elections would be held, so as to enable the country settle down under the leadership of a popularly-elected government,” wrote Richard Posnet, British High Commissioner to Uganda, to the Foreign and CommonWealth Office on August 14, 1979.

But in preparation for the elections, the ruling Military Commission, which had ousted President Binaisa, set up an inter-party committee to make electoral law amendments.

The committee recommended a total of 146 constituencies, and one ballot box instead of a box for each party, with all candidates on the same ballot paper, and votes to be counted at the polling station after voting. Party agents were to be present at each polling station.

However, the government did not implement any of the committee’s recommendations.

Government’s decision

It instead gazetted 126 constituencies and insisted on using the 1957 electoral laws.

Ill at ease, on November 14, the Democratic Party (DP) sent a delegation to Dar es Salaam to ask President Julius Nyerere to press the Military Commission to implement the inter-party recommendations.

Writing in Origins of Social Violence in Uganda 1964-1985 A. Kasozi says:

“(Tanzania President Julius) Nyerere insisted that he did not wish to interfere in Uganda’s internal affairs.

He advised (DP leader Paul Kawanga) Semwogerere to speak to (Military Commission chairman Paulo) Muwanga.”

Mr Muwanga appointed a five-man Electoral Commission chaired by Kosiya Kikira.

The other members were S. Egweu, Anania Akera, who had been Obote’s teacher at Gulu High School, and M. Matovu.

Vincent Sekkono was the commission’s secretary.

Nomination of candidates was a half-day exercise on November 25, starting at 8am to midday.

UPC had a candidate in each of the 126 constituencies.

By the end of the exercise, UPC had 14 of its candidates elected unopposed, with seven of them from the Lango sub-region.

Among the unopposed candidates were Apac South constituency candidate Henry Makmot.

“Mr Adoko Nekyon, the DP candidate did not show up for nomination,” says former deputy Finance minister in the Obote II regime.

Others in the race were Mr Stanley Omodi Okot, and Ms Teddy Odongo Oduka, Dr Obua.

But some opposition candidates point to sseveral tactics at play that had worked to deny them nomination.

Mr Israel Mayengo, who was a candidate for Masaka South on the Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM) party ticket, claims he was one of those who never made it to the nomination centre.

“On my way from Kampala to Masaka for nomination, I was held at a roadblock in Katonga for an hour. I reached the returning officer’s office Isaac Muwanga who was also the District Commissioner at 12.05pm, and he just told me I’m time-barred.”

Three days before elections, the Electoral Commission cancelled the nomination of three DP candidates in Kasese District. It instead declared UPC candidates as unopposed winners, increasing UPC‘s unopposed tally in Parliament before elections to 17 members.

The chairperson of Commonwealth Observer Group, E.M Deborah, sent a letter to Muwanga, protesting the Kasese declaration.

The former president of Uganda, Godfrey Binaisa. He is said to have supported the no-party election. FILE PHOTO

At the time of elections, the Military Commission-led government was broke to fund the elections.

Britain offered not only to pay for the printing of the ballot papers, but also paid for their transportation from UK to Uganda and also ensured their delivery in all parts of the country.

Nevertheless, the 1980 general election were conducted under the colonial law passed in 1957.

Under this law, the district commissioners were the returning officers for all constituencies in their respective districts.

They were also responsible for the hiring and supervision of the electoral staff in their respective districts.

In November, the Muwanga-led government dismissed 14 of the 33 district commissioners.

Their replacements were appointed by the Military Commission. No reasons were clearly advanced for the action.

But within the period, The Uganda Times of November 29, 1980, quotes UPC party president Milton Obote as warning that “civil servants should stop frustrating the UPC election efforts.”

The 1957 electoral law allowed for “the use of multiple ballot boxes and the counting of ballots at a central place in each constituency.”

But some parties opposed the use of multiple ballot boxes and a central counting centre in each constituency.

DP then warned that unless this was changed, they would boycott the elections.

Quoting Francis Bwengye, the DP Secretary General, The Times newspaper of November 4 wrote: “Multi-boxes will facilitate malpractice as was the case in the past when the UPC used to emerge victorious even though it had no support in the country.”

But the Electoral Commission stood its ground on the use of multiple ballot boxes.

However, with only five days to the voting, the EC agreed on having the counting done at the polling centre, not at a central place in each constituency

Besides using the 1957 electoral law, there were a number of flaws in the process that forced a UPM candidate, Mr Bakulu Mpagi Wamala, to go to court. But Justice Jermyn Peter Allen said: “He did not wish to stop the elections preparations since doing so would be extremely inconvenient and expensive.” (whose statement is this?).

Among other things that were being challenged were that the constituency boundaries had not been approved by the National Consultative Council (NCC), which was the substantive Parliament at the time, and that notice for voter registration was never gazetted.

Other complaints were about the choice of EC chairman, Mr Kikira, being a founder member of UPC, a party that was participating in the election.

The Commonwealth Observer Group threatened to leave the country before the elections.

Their concern was government’s refusal to separate the ballot boxes. The group had come under strict instructions to judge whether the elections had been free and fair.

The minister of Information, Dr David Anyoti, did not have kind words for The Commonwealth Observer Group.

“I hope you are here to observe but not to pass judgment on Uganda. Ugandans alone have the right to choose their government,” he said.

But Muwanga conceded, just three days before the polls were due, and agreed that the count would be done at each polling station.

On December 10, 1980, more than four million registered voters went to polling stations to do their civic duty.

It was supposed to be a one-day exercise, but the polling was extended to the next day because of late delivery of voting material even within some places in Kampala.

When the announcement was made for the extension of the voting to the next day, party agents offered to spend the night in the same room with the ballot boxes to protect their votes.

In the afternoon of the extended polling day, excitement of a DP victory started trickling in at the party head offices in Kampala.

Mr Makmot of UPC party candidate, who had been elected unopposed then residing on the flats above Shell Capital on Kampala Road recalls:

“At about 2pm, a large group of DP supporters had collected in the middle of Kampala Road, opposite the DP headquarters. Through the window, I saw a tall dark-skinned man in the middle of a swelling crowd, all chanting DP slogans at every announcement of the DP purported victories. In Tororo district all constituencies were taken by our candidates the man bellowed… in the West Nile region we have won all the constituencies except the one robbed from us by Dr Moses Apiliga.”

Talking to this paper in 2013, Samwiri Mwigusa, now deceased said: “I stood on the UPC ticket in Mubende North East constituency.

On the evening of the polling day, as the counting of the ballots was going on, we heard that DP supports were in the streets in jubilations.

By the time the counting ended that evening I had won the constituency.”

By the evening of December 11, given the agitation among DP fans, Mr Muwanga made a proclamation forbidding anyone besides him from announcing the electoral results.

The results’ authenticity had to first be verified and announced by him.

The observer team protested the directive, and Muwanga reversed it three days later.

But the EC was already in disarray. Its secretary was in hiding and the results it announced were presented to it by Mr Muwanga after he had verified them to be true, free and fair.

In the final announced results, UPC had secured 74 seats, against 51 for DP and 1 for UPM.

On top of the directly elected members, UPC had the chance to increase it numbers after the addition of 10 presidential nominees to Parliament and another 10 army representatives.

The COG team did not observe the tallying of votes at the constituencies, as they retreated to Kampala by the evening of the announcement.

But even before the official announcement of the results, they had issued an interim report offering a qualified endorsement, of the exercise.

The military commission used the COG’s interim report to announce that “the British government was satisfied that the elections were free and fair.”

At his swearing in ceremony, Dr Obote rode in a UK-registered car, escorted by a police Land-Rover marked ‘British Aid.

At the ceremony, Mr Muwanga asked DP to accept defeat as the people of Uganda had spoken through the votes, saying: “In the name of democracy and for respect for our country to respect the wishes of the people of Uganda.”

However, this was not something DP was going to take quietly. Writing in The Agony of Uganda, Francis Bwengye, a former DP secretary General, wrote: “Many countries, several multinational companies and some international organisations such as the Commonwealth Secretariat and the ‘Communist International’ as well as religious organizations played a big role in the Uganda elections and assisted Milton Obote to come to power fraudulently.