China in Africa: Beijing adds ‘strings’ to cement influence

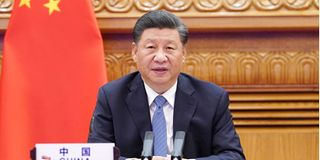

Chinese President Xi Jinping.

China’s influence in Africa may yet go beyond infrastructural development, a result of Beijing’s vision to prevent negative perceptions about its rise in the Global South.

A study by the Atlantic Council, a US think-tank, says sub-Saharan Africa, like most of the Global South such as Middle East or Latin America, have generally been amenable to China due to its ability to fund and build infrastructure in the region, a contrast from the West where Beijing is viewed in negative glasses.

This favourable view, the study known as ‘China’s discourse power operations in the Global South’ says, has been boosted by China’s expanding trade with the continent that has had both a scarce presence of good roads or railways, and mostly traded with the West before.

In sub-Sahara, Beijing has invested a cumulative portfolio of $23 billion since 2003. In 2020, Beijing was building about a third of all infrastructure projects on the continent, worth about $50 million or more, according to an analysis by audit firm Deloitte, compared to just under 12 percent by the Western firms.

Also Read: Kenya's debt to China hits Sh797bn in May

According to China’s General Administration of Customs, trade with Africa grew by 35.3 percent in 2021 to reach $254.3 billion.

In the first three months of 2022, the department says trade with Africa has risen by 23 percent from 2021 figures. China’s continual lockdowns and reduced port operations have probably kept the figure lower than expected.

Yet China is not only about trade and infrastructure. In fact, the Atlantic Council report says Beijing is just as keen to protect its image and prevent a negative influence about its elevated ties, by the West.

“As China’s military and economic power has grown, so too has its investment in propaganda and influence operations,” say the researchers in the report.

“Following Xi Jinping’s rise to power and China’s adoption of a more confrontational foreign policy, the country saw a need to sway global public opinion in its favour. Beijing refers to this as “discourse power”.”

This strategy, they say, seeks to have pro-China narratives promoted while criticising rivals with the goal of shaping the world to be more perceptive of China’s standing.

And one way of doing that is expanding attachment to the Global South where it has adopted Two pillars of using state-run media with offices abroad and using international platforms to sell its image including at UN forums.

Beijing rejects the idea that it has coerced new allies to toe its line. Instead it accuses Western countries like the US of “patenting” coercion.

“China never coerces others, and we firmly oppose coercion by other countries. One of the traditions in China’s diplomacy is that we believe all countries, big or small, are equal,” argued Zhao Lijian, spokesman of China’s Foreign Ministry at a recent press briefing.

“China never threatens other countries with force. We never form military coalition or export ideology. We never make provocations at others’ doorstep or reach our hands into others’ homes.”

However, the researchers observe that China is in fact pushing for influence beyond trade and infrastructure by selling its own principles to the Global South which could ultimately ensure its interests are protected.

For example, Beijing’s non-interference in the internal affairs and the concept of human rights as coming second to economic development, are a subtle push against Western narratives.

“It is meant to stand in opposition to a Western human rights framework that China criticises as having been used for interventionist ends, for example, in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“Beijing also sees control over the media environment as critical for enhancing its discourse power so that it can spread a positive “China story”. In doing so, it is better able to promote its image as a responsible power and gain support for China’s model of international relations,” the report says.

Such a model will privilege sovereignty, economic development and control over civil liberties.

In addition, Beijing has been expanding the role of multilateral and regional organisations including the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Africa, the Forum of China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (China-CELAC Forum) in Latin America, and the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF) in the Middle East.

As they often bring together countries from particular regions, Beijing is able to enhance its engagements with each one of them, enabling it to market ambitious projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and still build the organs as arenas for equal discussions.

This strategy may invariably be known as the “subcutaneous injection” meant to win friends and isolate spoilers.

The researchers say that eventually, China’s story will be retold by the new friends for a more “immediate and quick” dissemination of own priorities.