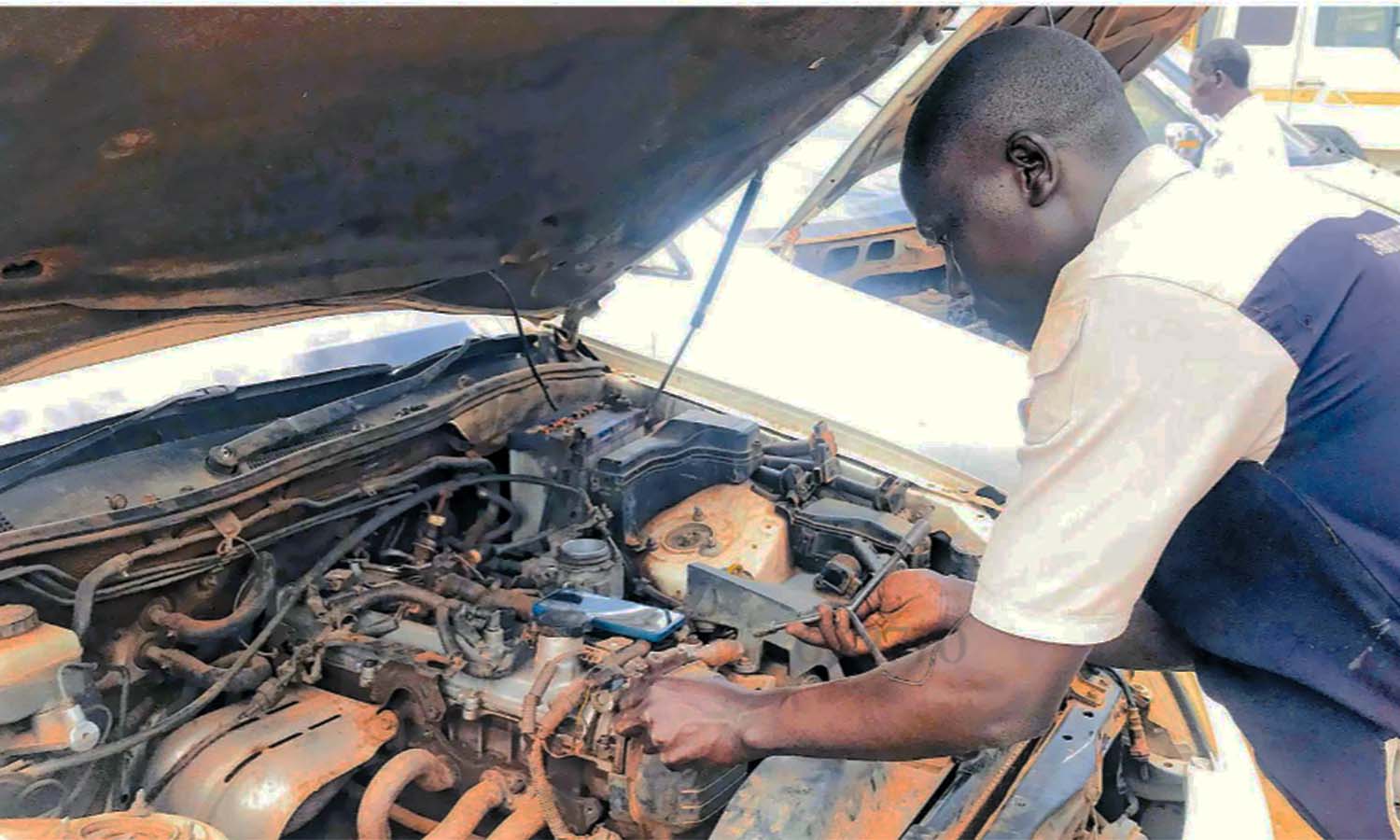

When he had just bought the Cooper at a price he shies away from sharing, Kabali’s 57-year old Mini Cooper was not in a roadworthy condition. Photo/s by Michael Kakumirizi

In the mid-1990s, Geoffrey Kabali set out to buy a vintage car. He was sure he needed a Mini Cooper of any model or year of manufacture. His love for Mini Coopers is something that stretches from as far back as the 1960s when his father owned and often drove him and his siblings to different places in the car.

Later as an adult, when he could afford it, Kabali embarked on a manhunt for a Mini Cooper to buy. When he could not find one on the road to buy in 1995, 1996 and 1997, he cast his nets wide to far flung places such as Gulu and Arua districts in northern Uganda and West Nile in search of an abandoned Mini Cooper he could buy and restore. It was until 1998 that he chanced on one in Kayabwe on Masaka Road that he bought from one of the local artistes whom he recalls sold it to him handsomely because they highly valued the car.

“During inspection and the price negotiation process, I discovered that the car was manufactured in the same year I was born. I did not hesitate to conclude the deal and after a few days, I had it transported on a car carrier to my home in Bulenga, Kampala. I have owned it since 1998,” Kabali says of the 1967 model.

Restoration process

When he had just bought the Cooper at a price he shies away from sharing, Kabali’s 57-year old Mini Cooper was not in a roadworthy condition. He replaced the radiator and made a few repairs on the engine and gearbox. As he carried out test drives in his home compound, he realised the old engine and gearbox would be problematic along the way. He imported a new engine and gearbox, which came into his possession in 2021, shortly after the second Covid-19 lockdown.

“Being an old model car, it is hectic and challenging to source for spare parts. I got most serviceable parts from the United Kingdom via eBay and Amazon. I buy part by part because the wear and tear takes place at different times. It uses size 12 tyres but they are also not readily available. I visited almost every spare parts centre in Kampala until I found them in the Industrial Area. Each tyre cost Shs270,000,” Kabali recalls.

Photo by Michael Kakumirizi

Gearbox delay

To date, Kabali has not yet fixed the new gearbox and engine he imported at approximately Shs12m. He has taken two years without driving the Cooper because he is still saving money to remove the old engine and gearbox for the new ones, but also rework the car body, all at once.

All this is expected to be complete by October, so that the car can participate in the annual classic and vintage drive. However, he sometimes checks on the functionality of the car by driving it around his compound. The longest distance he has driven it since 1998 when he acquired it was from Bulenga to Kajjansi when the Entebbe expressway had just been opened for public use.

“I service it myself because most mechanics do not understand the old technology of vintage cars. I am not a mechanic but I use knowledge and experience I gained over the years from driving vintage cars. It doesn’t require any expertise. I change the engine oil and plugs and a few serviceable parts and lubricants,” Kabali says of the car that runs on a manual transmission with four gears, with the fifth being the reverse gear.

Specs

Designed with a seating capacity of five, the Mini Cooper runs on a 1100cc petrol engine. On average, he spends approximately Shs150,000 to Shs200,000. Unlike most cars that are serviced after covering 5,000km, Kabali services the Cooper before it goes on the road because it is parked most of the time. Because of its low ground clearance, he has never driven the two-wheel drive car off-road for fear of causing damage. It is also a car he argues can accommodate motorists of any height because of its ample leg room, much as it is small.

“Do not talk about selling this car. I cannot attach any monetary value to it. Someone once tempted me with a bag of Shs30m cash but I turned down the offer. Many people thought I was crazy. It is the most treasured vintage car I have owned,” he says.

Advice

Kabali says if you intend to buy any vintage car, not just the Mini Cooper, be ready to spend on it because they are cars one buys, restores, maintains and drive out of passion. Most, if not all vintage vehicles, are historical cars that will never be in production again, the reason he urges the government and institutions such as the Uganda Tourism Board to work with private vintage car owners to ensure they are preserved for generations of enthusiasts to come.

“As a country, we are not good at preserving history. It is time the government starts looking at old vintage cars as items to attract tourists to this country. If the car in which former leaders such as Idi Amin drove were preserved, many tourists would pay to see the car but we just crash historical collectibles like they never existed. It’s the country that loses, not individuals,” Kabali concludes.