Prime

Ssezibwa, the village mechanic who became welding wizard

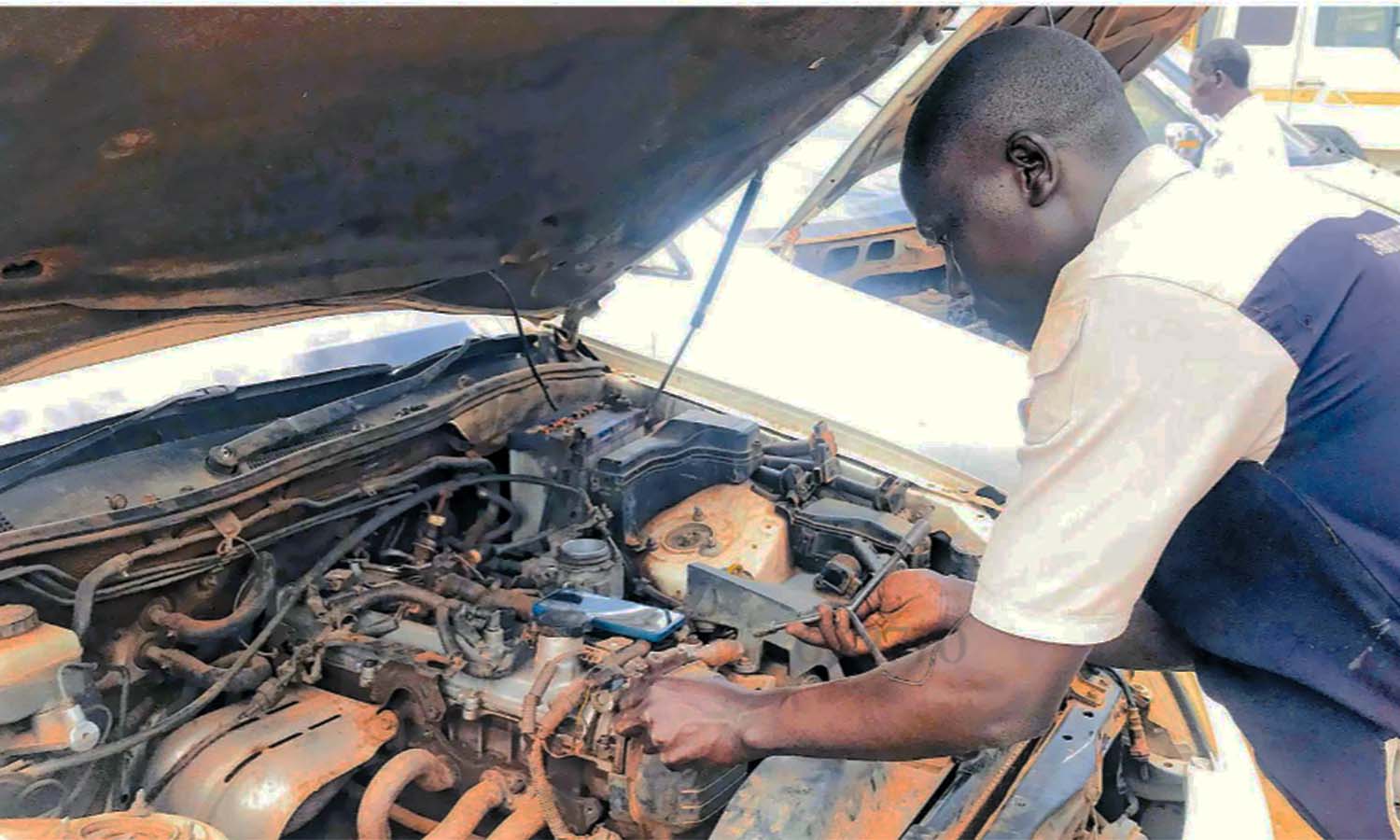

Mr Ronald Ssezibwa, the CEO and senior welding technician at SEB Engineering Services,

ABDUL-NASSER SSEMUGABI

By the 20th anniversary of his company, Ronald Ssezibwa, the CEO and senior welding technician at

SEB Engineering Services, promised himself a cheque of $10m.

Yet his biggest dream since, high school is establishing one of the best vocational centres across Africa. Unlike his pessimistic colleagues, Ssezibwa strongly believes it is just a matter of time, inspired by the small beginnings and giant leaps over the last 13 years.

What started in 2007, in a container in Kasubi, Hoima Road, designing forex bureau interior, is now an industrial enterprise sitting on a half an acre, with modern welding staff and technology, hired by multinational clients to produce tanks, structures, warehouses, bridges, and more.

The baby steps

Ssezibwa was already the village technician by Primary Four, fixing radios and television sets.

Reading his father’s science books gave him an edge over others and his science teacher nicknamed him Socrates [the great Greek philosopher].

After his A’ Level at Bishop’s Senior School Mukono, Ssezibwa studied electrical engineering at Masaka Technical College on government sponsorship. Concurrently, he sponsored himself for a certificate in computer maintenance.

Ssezibwa’s hero is his father, Charles Mugera Bbaale, a hardworking farmer and welder, who trained his children several ways of sustenance: poultry, brickmaking and more.

His father told him he wouldn’t support him beyond college and after achieving his a diplomas in 2004 with some mechanical engineering knowledge, Ssezibwa worked with Electrical Energy Accessories, a now defunct company, where he got vital experience and exposure.

He fixed three-phase generators, among other tasks, earning Shs100,000 a month of which he saved Shs15,000 for six months.

“But I was a target worker,” Ssezibwa says. “I was determined from the onset that no matter how comfortable I would be, I wouldn’t be employed beyond two years.”

He quit in 2006, to try the uncharted waters of self-employment, towards his cardinal dream of entrepreneurship. “It was a hard decision because I had even got a family,” he recalls.

From his small savings, he rented a container in Kasubi, Kampala, where he established a library.

At the college he had helped tutors in practical electrical lessons and now sourcing for capital, he did everything from burning CDs to repairing electronics to electrical installation in Kampala and suburbs. But Ssezibwa needed a hand for his bigger dream of starting a company and vocational institute. His colleagues dismissed the idea as “too big and unrealistic.”

Ssezibwa did not give up. From the library he got Shs250,000, and hired a lawyer who guided him through forming SEB Engineers Services Ltd. (SEB means: Surveyors, Engineers and Builders, premised on the American Welding Society module of surveying a problem, building awareness and engineering a solution). In August 2007, he formalised the company.

He bought tools and upon bidding for a government contract in 2008, he registered for tax, which many businesses avoid. His bid failed, but in 2009 he got a breakthrough.

A friend connected him to a job of designing Dahabshil Forex Bureau in Arua for Shs19m. “We camped there for three months,” he retells. “My target was to make a name to attract more such contracts.”

Out of the Shs4m profit he bought more equipment: a computer, a drill, and a cutter.

Deals started flowing in. In 2010, the same client gave him another job worth Shs150m to design another branch bureau on Bombo Road. From the handsome profit, he bought more tools and a piece of land—according to plan—in Gombe-Kayunga, Wakiso, where he later built a home and the company’s headquarters.

He had won the client’s trust as he recommended him to many others. “That trust is the biggest wealth on earth,” he says.

In 2011 Ssezibwa bagged $24,000 (about Shs60,000,000) and a bonus of $2000, from another client from UK, to design a forex bureau on Luwum Street in Kampala. He designed many more on Kampala Road, and the Nigerian High Commission in 2013. He also worked for Spedag Uganda.

Setback

In September 2013, sponsored by Chamber of Crafts in Cologne (HWK), Ssezibwa went to Germany to upgrade his mechanical engineering skills, especially in welding and fabrication. (He has been to Germany twice more and Finland, mainly to benchmark).

By then he had shifted into a bigger office, across the road in Kasubi, but in November fire gutted the premises and he lost equipment worth Shs300m. “I almost went back to zero. But my strategic plan and passion helped me to recover.”

In 2012, he had hired Simon Senkaayi, a business consultant to draft a 10-year business proposal of $13m. (about Shs47bn).

All that revenue would be generated from selling the company’s products and services, not borrowing. And even after the tragic fire, Ssezibwa bought the equipment, gradually, without acquiring a loan.

He also specialised in mechanical engineering, as the company’s niche, and seven years later, the fire is history.

He attributes this success to strategic: planning, management and implementation.

“And if you want success, never be selfish,” he adds. “Share the things you cherish and God will bless you with more.”

Grand plan

By 2010, the company had accumulated a seed capital of $100,000 (nearly Shs250m, according to the exchange rate then).

And in 2026, the company is projected to have capital of $19m.

In the 2012-2022 strategic plan, the company listed ROKO Construction, Nexus, New Plan, Gentex, Tirupati and some vocational institutions as its serious competitors.

But SEB believed its technology, unique manufacturing and education concept and a self-contained facility, would capture a large market share.

The company also has a target of acquiring high-end machinery worth $1.4m by 2021, which can help in manufacturing smaller equipment like metal sheet rollers.

Eight years on, Ssezibwa rates the progress at 60 per cent. “Getting $13m is just a matter of time.”

SEB has trained about 250 professionals, some working in the United Arabs Emirates. The company will soon build its dream facility on a new site, which will also accommodate the vocational institute, to fully champion its education and manufacturing model.

Sacrifice and dedication are key: “I promised myself a cheque of $10m after 20 years, but to achieve it, I must respect the company and work for it as if it’s my boss.”

He adds, that to help the company build a legacy for future generations, he reduced personal desires and increased company desires. “So even if I get personal money from, say consultancy, I invest it in the company targeting return on investment,” he says.

Strides and challenges

The wooden wall facing the office door is plastered with papers detailing several company policies, regarding health, safety, environmental safety, ethics, grievances, and quality, among others.

This has greatly helped SEB even attract international clientele and partnership.

When we visited the workshop, Ssezibwa was welding the four nine-metre steel poles for the suspension bridge in Kasese. SEB was contracted by Bridges To Prosperity, a US–based non-government organisation partnering with the government of Uganda to build 11 bridges in Sironko, Bulambuli, among other hard-to-reach areas.

It takes SEB a month to manufacture one bridge, using highly sophisticated technology.

Work is shared in specialised shifts but the welding part is entirely Ssezibwa’s duty. “Because I know the lives of the bridge users depend on the strength of the joints.,” he notes.

However, corruption has cost the company some deals. “Give me the job on merit, but I can’t bribe you,” Ssezibwa says with a stern look.

He is also selective. “Nowadays, we only deal with those who respect and appreciate our integrity and professionalism.”

The lack of competent and committed human resource has also tempted him to procure robots to execute some tasks.

The Uganda Business and Technical Examinations Board assessor adds: “Our education system should also change to expose learners to more industrial practice.”

Coming innovations

The company manufactures agro food machinery and farm implements, provides renewable energy solutions (bio gasification and electricity), apprenticeship industrial training and general construction and engineering.

Guided by market research and creativity, each product version must be better than the previous one, without necessarily increasing the price.

Say, if the first version of the eco-friendly stoves emitted 75 per cent less smoke and used 50 per cent less charcoal, the 2021 version can emit 80 percent less smoke and use 65 per cent less smoke.

Innovative

SEB is developing automated car parking systems, which can accommodate six to 24 cars, one above the other, in a space that would accommodate only two cars.

They manufacture car jerks, ramps, and are planning to venture into manufacturing trailers.

Next year, they plan to intensify the manufacturing of wood gas generators as alternative energy for forklifts, trucks, industrial stoves, among others.

SEB is planning to produce up to one megawatt of power from agricultural waste.