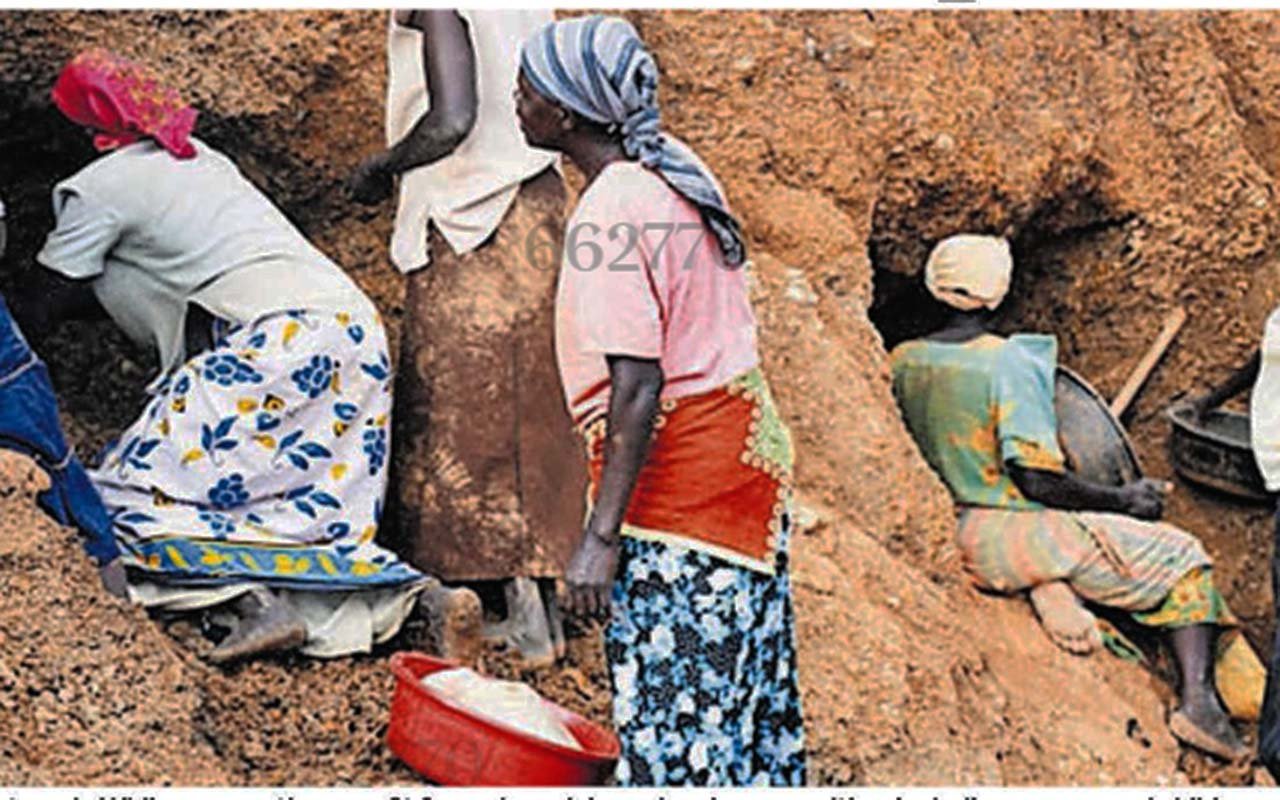

Miners at work. While corporations profit from cheap labour, local communities, including women and children, often bear the hidden costs of unsafe conditions and poverty. Photo/File

Imagine a mining company in Uganda, nestled in a rural community. It builds a top-tier hospital for its workers, but when a child from a nearby village is hit by a car, it’s the only hospital that can save her. Does the company have a duty to treat her, even though she’s not an employee? The answer is yes. The company, as the only option, is the gatekeeper to her right to healthcare.

If 20 kids were injured in a bus crash, the company would likely still be responsible—unless there’s another hospital nearby. But should the company also light up the roads or provide free healthcare? Some argue it should, seeing as the kids are vulnerable and the danger is recurring.

But how far does this responsibility go? Should the company provide food, build schools, or supply water? If it has the resources, it might be expected to do more—but only within its capacity. If other companies are around, the burden could be shared. If one company falls short, should others step in? The answer, as supported by South African human rights researcher, Prof Bonita Meyersfeld, is yes.

In her September 2024 paper, Corporations and Positive Duties to Fulfill Socio-Economic Rights, Prof Meyersfeld argues that corporations have a legal duty to fulfil socio-economic rights, regardless of what other companies are doing. If a corporation fails to meet these obligations, regulations should enforce compliance. Without such regulations, the burden could unfairly fall on other companies, forcing them to take on more responsibility than they should.

Prof Meyersfeld, from the University of Witwatersrand, believes that corporations benefit from structural poverty, where widening wealth gaps lead to higher profits at the expense of human rights. In her view, businesses should not profit from this inequality but instead play an active role in addressing it.

“While corporations adopt public corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes, this does nothing to break the cycle of poverty. If corporations fail to alleviate poverty in the areas in which they operate (ie host states), and if that status quo is one that fails the human rights of millions of people, then we must ask whether the current status of international human rights law is fit for purpose. I argue that it is not,” she writes.

Relying on corporations to act responsibly is like trusting a fox to guard the henhouse—when they fail, human rights take the hit. Local laws often don't hold companies accountable for perpetuating poverty, so international law must step in to impose clear duties, especially to support socio-economic rights.

Prof Meyersfeld argues that international law should hold corporations accountable for fulfilling socio-economic rights, though not equally for every company—size and resources matter. Big corporations profit from cheap labour, directly perpetuating poverty, and that triggers their responsibility.

Currently, corporations only have to avoid violating rights, but this "negative obligation" is outdated. Researchers like Prof Meyersfeld advocate for "active positive obligations," meaning companies must do more than just avoid harm—they should actively improve situations.

International human rights law outlines four duties: protect, respect, promote, and fulfil rights. The "fulfil" duty means corporations should take specific actions to realise those rights—even at a financial cost. Avoiding harm can also be seen as fulfilling rights, especially when exploitation is involved.

Structural poverty

Structural poverty is a harsh reality in developing countries like Uganda where it deprives people of basic resources and violates socio-economic rights. It’s not just about low income; it also includes poor health, education, and living conditions.

The traditional income-based poverty measure has been replaced by the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which accounts for factors like nutrition, child mortality, education, housing, and access to utilities.

Poverty leads to instability, hunger, and homelessness, eroding dignity. Over 21,000 deaths daily worldwide are linked to poverty and inequality, with children suffering the most from malnutrition, poor sanitation, and lack of clean water. The cycle is relentless—children born into poverty face a lifetime of poor health, limited education, and limited economic opportunities, making escape from deprivation difficult.

Prof Meyersfeld’s research shows that structural poverty in sub-Saharan Africa is deeply embedded in the global economic system, rooted in historical exploitation and the persistent inequalities between the Global North and South.

As she writes, “The rules of international trade and economic law were created by Global North states at a time when most Global South states were still under colonial rule. These rules have allowed the economic legacies of colonisation to perpetuate the stratification of the global economy along the Global North/Global South line.”

Scholars from Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) argue that international economic law has institutionalised global poverty by reinforcing the power dynamics set up during colonialism. International financial institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Trade Organization (WTO) exacerbate these issues by imposing structural adjustment programmes on poor countries, prioritising austerity and market liberalisation, which often hinder local poverty alleviation efforts.

The policies of wealthy nations—such as subsidies, protectionism, and exploitative trade practices—further skew the global economy in favour of the Global North.

Colonial relics

Unfair trade agreements, intellectual property rights on essential goods, and discriminatory policies continue to cost developing nations billions of dollars annually. And there are examples to it. The European Union coffee subsidies mean Uganda’s beans are priced like bargain-bin goods, patents make life-saving drugs costlier than a luxury car for many Ugandans, in 2007, Uganda fought pharma giants to make cheaper ARVs—big pharma wasn’t having it. And Monsanto’s seed patents keep Uganda’s farmers locked out of affordable, reusable crops.

Beyond economic exploitation, racial and gender inequalities continue to shape global labour markets. Jobs in mining, cleaning, caregiving, and teaching—typically filled by marginalised groups—are undervalued, despite their societal significance. This injustice, a relic of colonialism, persists in devaluing labour based on race and gender.

There is clear evidence that wealth is still being transferred from poor to rich countries, perpetuated by political and economic structures, with multinational corporations (MNCs) playing a central role. Research in the Political Economy Journal reveals that since 1960, rich countries have drained $152 trillion from the global South—a legacy of imperialism, now taking a new form.

MNCs directly profit from structural poverty in developing countries, exploiting cheap labour, lax regulations, and low taxes. These companies target impoverished nations to avoid the higher operational costs of developed economies. While they claim to create jobs, the wages they offer are insufficient to meet basic needs, leaving workers in debt rather than improving their lives.

The connection between corporate wealth and poverty is further entrenched when communities effectively subsidise corporate profits. In mining, for example, unsafe working conditions often see women providing unpaid labour to care for injured workers—an unacknowledged subsidy that lets corporations profit while contributing little to local welfare. As corporate profits soar, they often do so at the expense of the poor, with companies complicit in violating socio-economic rights.

While MNCs may not always directly cause poverty, they benefit from systems that perpetuate inequality, aligning with the "beneficiary pays principle"—those who profit from injustice should compensate the victims. This means corporations should be held accountable for their role in reinforcing poverty.

Illicit financial flows

MNCs also contribute to illicit financial flows (IFF), draining resources from developing nations through corruption, smuggling, tax evasion, and trade mis-pricing. Africa alone has lost over $1 trillion in illicit financial flows in the last five decades, stifling governments' ability to invest in social welfare, according to the Tax Justice Network Africa.

The corporate claim that investments create jobs and lift the poor often rings hollow. For example, in Uganda, the Auditor General’s 2022/2023 report revealed that 22 of 36 companies receiving tax incentives failed to meet employment targets, raising red flags among lawmakers and economists. This gap between corporate promises and reality highlights a broader issue of corporate complicity in global poverty.

Despite claims of regional development, major corporations still prioritise profit maximisation, reinforcing global economic inequalities that sustain poverty. The UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights may sound ideal, but they fail to hold corporations directly accountable for human rights violations, leaving it to states to enforce regulation. In poorer countries, this creates a "race to the bottom," where weaker laws attract businesses, but at the cost of human rights and environmental standards.

With companies "self-regulating" in such environments, it’s time to stop hoping they will play fair and make them directly accountable. The failure to hold corporations directly accountable under international law creates a glaring gap in enforcing global justice for socio-economic rights, particularly in the poverty-stricken Global South.

Unlike traditional models, this approach holds corporations responsible even without direct relationships with affected communities, arguing that their profits from inequality make them complicit in human rights violations. It challenges the idea that positive duties should be rare, asserting that such obligations should be widespread, especially given the rampant exploitation in poorer regions.

While poverty is often dismissed as a long-term issue, Prof Meyersfeld argues that poverty-related violations—like hunger, homelessness, and hazardous living conditions—are a relentless, ongoing crisis. Structural poverty creates continuous deprivation, making intervention urgent at all times. The gatekeeper principle complicates this further, as corporations controlling access to basic rights must consider their capacity to fulfil them.

Key questions include whether a company can allocate enough resources, whether it has the expertise to address specific rights, and whether fulfilling those rights is financially feasible without risking operations.

The definition of "affordability" is subjective and often skewed toward profit over social responsibility. To address this, a more objective standard is necessary, incorporating factors like liquidity, tax rates, and the financial health of parent companies.

Prof Meyersfeld suggests that collaboration between human rights experts, corporate lawyers, and economists is crucial to ensuring a fair assessment of corporate duties to uphold socio-economic rights.

Budgeting

Budgeting for socio-economic rights might seem tricky, given the uncertain and often unquantifiable costs, but corporations already handle similar uncertainties—think insurance companies predicting claims or businesses accounting for market fluctuations. These established practices can be adapted to include socio-economic rights in their budgets.

While resource allocation is a debated issue, the uncertainty around it shouldn’t be an excuse for corporations to avoid their duties.

“Just as companies prepare for unpredictable risks, they should factor socio-economic rights into their financial plans, ensuring they meet these obligations just like any other business expense,” writes Prof Meyersfeld.