Prime

Busy but ‘unemployed’

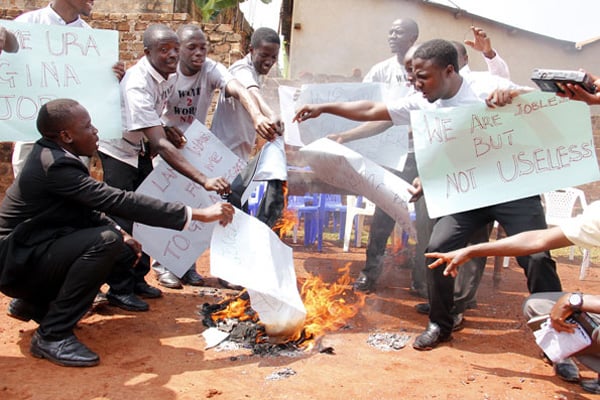

In this file photo, members of National Association of the Unemployed burning placards after addressing journalists in Kampala in 2014. There is an army of mostly young Ugandans who are effectively unemployed. WB data shows that among youth, three out of five work in unpaid occupations, contributing to household enterprises. FILE PHOTO

For six days a week, Paulo Ssegirinya is in his half-acre garden before sunrise. He then tills the land, taking a break when it gets too hot and humid with the sun overhead, before returning when it becomes cooler.

A few kilometres away but what feels like a world away from his garden, Sarah Kansiime spends hours on her feet. Her job is to go from one office to another, shop to shop, collecting lunch orders, which she delivers, then returns to collect the dishes.

For each plate delivered, Ms Kansiime is paid Shs200. It is hard to tell whether Mr Ssegirinya, a master of his destiny who eats what he grows, is better or worse off.

While both live hand-to-mouth, they are far apart in the world of counting jobs. Mr Ssegirinya would be considered ‘employed’ in agriculture, while Ms Kansiime would be counted among ‘wage earners’. Strictly speaking they are both in disguised unemployment.

Ms Kansiime has to deliver at least 20 plates of food to crawl past the UN poverty line of $1.20 (Shs4,458) per day, and about 50 just to earn Shs10,000 a day.

Mr Ssegirinya is hardly better off; he is perpetually broke and the food he grows is largely for home consumption. While both are busy, hardworking and technically ‘employed’, they are part of a large army of unemployed but busy Ugandans.

Unemployment

According to World Bank data, access to employment is high, at 77 per cent of the 15 to 64 age group compared to an average 70 per cent in low-income countries.

But, as a recent World Bank (WB) report on jobs notes, “most Ugandans work because they cannot afford not to”. The quality of jobs is poor, with only one in four employed Ugandans in wage employment. The majority work for themselves or for their families.

Dino Merotto, author of the World Bank report, says the widespread belief that many of these are entrepreneurs running their own small businesses (Uganda is routinely listed as one of the most entrepreneurial countries in the world) is incorrect.

“This statistic should not continue to be misinterpreted as meaning that most workers employed outside agriculture are self-employed. They are not,” Mr Merotto notes. “Half of off-farm work in Uganda is not ‘subsistence entrepreneurship’ but waged-work, mostly in low productivity, informal micro enterprises, and there is not enough of it.”

There is an army of mostly young Ugandans who are busy with this and that but who are effectively unemployed. WB data shows that among youth, three out of five work in unpaid occupations, contributing to household enterprises.

Working hours are irregular with nearly half of all workers working fewer than 35 hours per week.

Most of this reflects dependence on rain-fed subsistence agriculture where labourers, on average, work for fewer than 30 hours a week and earn less than Shs130,000 per month.

According to the 2016/17 Uganda National Household Survey, 65 per cent of the working population was engaged in agriculture.

The same survey estimated the total employed population at nine million out of 15 million ‘working’ people. The ‘missing’ six million are probably people in unpaid work – the ‘busy but unemployed’.

Vulnerable employment

This category is often characterised by poor earnings, productivity and working conditions. The household survey noted that 57 per cent of all employed persons aged 14 to 64 are in vulnerable employment. About a third are in agriculture, forestry and fishing, followed by sales, maintenance, repair of motor vehicles and personal goods.

Further pervasive features of the Ugandan labour market are underemployment and working poverty. Overall, weekly hours worked are below the international standard of 40 hours per week. Agriculture, the largest employer, also has the lowest average working hours per week, for both men and women. The services sector, however, averaged 49 hours per week.

An employment diagnostic report from 2018 by the Ministry of Labour found that only 34.5 per cent of all employed people were wage earners. But even wage earners had little to write home about, with a median monthly wage of Shs200,000.

Self-employed and contributing family workers accounted for 52.8 per cent and 9.8 per cent respectively, meaning more than six out of every 10 workers are in vulnerable employment. Eight out of every 10 people employed outside agriculture are in the informal economy.

Only eight per cent of employed Ugandans are in manufacturing and about six million had not sought work because of discouragement.

“In view of the less-than-satisfactory labour market outcomes and in accordance with the mandate of the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social development under the Employment Policy 2010, an employment diagnostic analysis was commissioned,” Mr Martin Wandera, a director in the ministry, said.

High-sounding words for a high-priority problem.