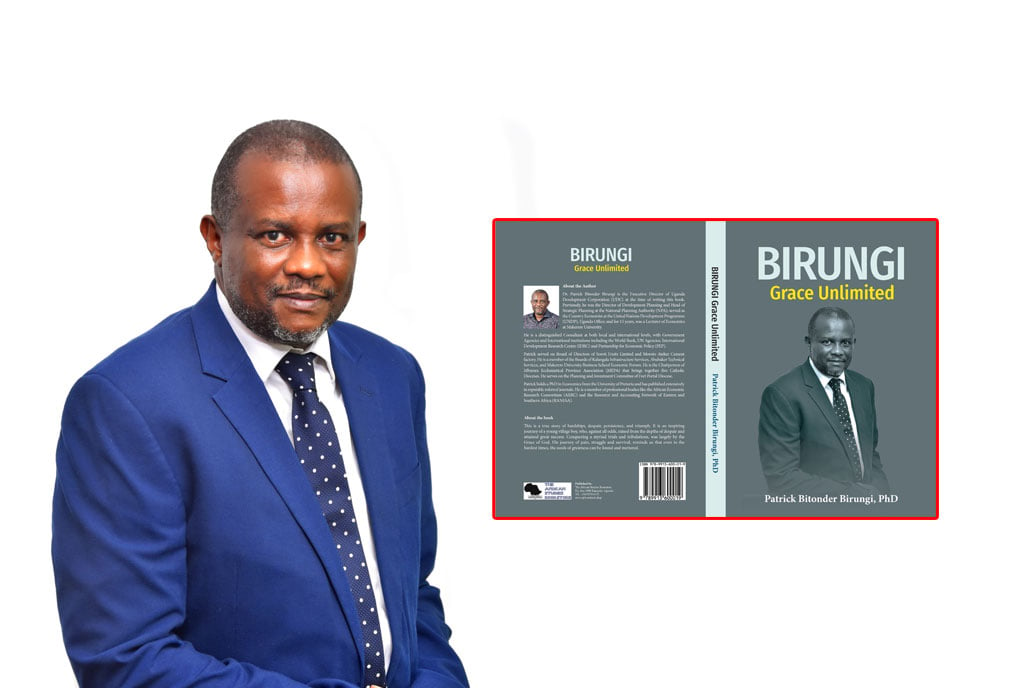

Heights the Preacher recites a poem at an event. The poet uses street languages in his poetry. PHOTO/PHILLIP MATOGO

Street poetry is an art form slowly replacing traditional poetry in Kampala. It is doing so with the unfiltered dialect of urban life, whose poetic expression emerges from the concrete jungle to highlight the lowlights of the city, the struggles of city slickers, and the uncommon hidden in the commonplace.

Still, this is only happening at the level of language; and not at the level of performance. In other words, Uganda has street poetry but no street poets.

In this vein, Kampala, and other cities in Uganda, have not witnessed their streets being invaded by poets in the same way they are populated by street preachers whose itinerant ministries take them everywhere in service of their faith. Despite Ugandan poets not performing on the streets, their language is largely from there.

So why the disconnect, you ask? Well, to understand that, we must realise that street poets outside Uganda, like street preachers inside Uganda, are possessed of a heightened degree of boldness. Ugandan poets are still a little diffident, unwilling to go the whole hog in service of poetry.

Origins

All said, where did street poetry come from? A quick Google search turns up some interesting results. One states: “Street poetry traces its roots back to ancient oral traditions, where bards and troubadours wandered through marketplaces, taverns, and alleyways, reciting verses that spoke of love, loss, and the human condition.”

It proceeds to add: “Fast forward to the modern era, and street poetry finds its home in bustling metropolises, where poets scribble their verses on subway walls, abandoned buildings, and city sidewalks. It’s a rebellion against the sanitised confines of traditional poetry, a refusal to be confined within the pages of a book.”

Street poetry is punctuated by the rhythm of everyday conversations. So you will find it seasoned with slang and vernaculars, which help the poet connect with the audience in a raw and authentic way.

Ugandan performance poets ranging from Ssebo Lule to Heights The Preacher use this street language in their poetry. So they play fast and loose with the formal rules of language as they employ colloquialisms, code-switching, and nonce words (also called an occasionalism—is any word (lexeme), or any sequence of sounds or letters, created for a single occasion, an example of which is Togikwatako—“Don’t you dare touch [the Constitution]”).

This approach, unbound by verbal rectitude, democratises the art form. It doesn’t require a literature degree, just the poet’s finger on the pulse of the city.

Global phenomenon

Street poetry thrives worldwide. In São Paulo, Brazil, the Beco do Batman (Batman Alley) is adorned with colourful murals and poetic lines. In New York City, US, the Nuyorican Poets Cafe has been a hub for spoken word artists for decades. And in Cape Town, South Africa, the vibrant street art scene includes powerful poetic messages about identity and history, according to Wikipedia.

In Uganda, however, we don’t see poets stomping the streets with defiant turns of phrase, which designate the streets as the poet’s natural habitat. As a result, poetry in Uganda is elitist. Sure, it might employ the everyday language of everyday Ugandans, but if that language is not rendered directly to the average Ugandan, through poetry, its poetic form is removed from our collective consciousness.

Obviously, a poet, once the transition to performing on the streets is made, will have to commit class suicide. That’s because poetry is usually performed in the kind of deluxe establishments that the ordinary Ugandan identifies as unfriendly to one’s pocket.

To be sure, poets favour such venues because not only are they poetically-compliant, with their plush interiors and well-heeled clientele, they also mirror the poet’s self-image as a cultured person of style.

No money

The irony here is that although such expensive establishments are haunts favoured by those who can buy a beer at three times the Kafunda price, the poets gather very little moss here. While in such an establishment, the poet is expected to perform a poem or more. If that poet partners with the establishment to bring in more patrons, a percentage of the bar sales or a nominal fee will be paid to the poet at the show’s end. This can range from Shs10,000 to Shs300,000, the latter representing a hugely successful show.

If the poet brings their own team and equipment, only using the venue for utilities, while charging an entrance fee, the financial gains are even more marginal.

So why can’t poets introduce more people to poetry by performing freely on the streets?

This way, poetry is popularised to the average person and is imbued with a marketplace appeal, previously reserved for musicians and comedians.

To be sure, stand-up comedians used the streets to reach a mass audience and parlay such access into better pay when these audiences proved to be steppingstones to more remunerative venues.

Becoming Dave Chappelle

In the late 1970s to early 1980s, a public park called Washington Square Park in New York City, was the staging ground for some of the most crowd-pulling stand-up comedy. The street comedian Charlie Barnett would jump up onto a park bench and shout: “It’s show time!” and do a 20-minute stand-up set that left the whole parking lot laughing its hindquarters off. Barnett quickly saw that his comedy was better suited to street performances than the comedy clubs.

One day, Dave Chappelle, who was due to play Barnett in a 2005 biopic that was never made, was booed off the stage of the Apollo Theatre. Chappelle was only a teenager when Barnett took him under his wing and showcased him to the crowd in the park.

After watching Barnett, Chappelle cried and said: “I’m never going to be as funny as that guy.” But Barnett mentored Chappelle and “kind of advanced me, skill-wise. Just exponentially. Charlie taught me how to be fearless working outside.”

With Chappelle widely considered as stand-up comedy’s greatest performer, we see the role street comedy played. Street poetry can do the same for Ugandan performers.