Book Review: Book offers lowdown on kings of Buganda

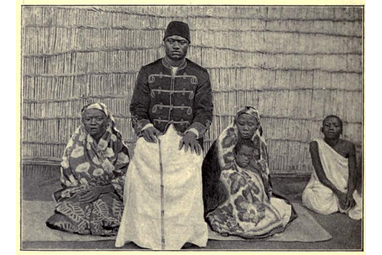

Sir Apollo Kaggwa. Photo/Courtesy

What you need to know:

- Book title: The Kings of Buganda

- Author: Sir Apollo Kaggwa

- Price: Shs30,000

- Where: Aristoc Bookshop

“The case of Apollo Kaggwa is instructive, for he was no ordinary native official. The Colonial Office file on the subject recognises that he ‘rendered’ invaluable help to the British during the perilous days of mutiny, as well as, finally, against the remnants of the Sudanese,’ and goes on to confirm: ‘it is no overstatement to say that had his prestige and authority been cast at that time into the balance against the British raj, European influence would have been entirely, if not temporarily, eclipsed.’” wrote Professor Mahmood Mamdani in his engrossing book, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism.

Kaggwa was a historian and an author as amply revealed in his book “The Kings of Buganda” which is translated and edited by the towering historian M.S.M Kiwanuka.

In this book, Prof Kiwanuka outdoes himself with a thoroughgoing rendering of the history of Buganda kingship (1300s-1884) as told by a former Katikkiro (prime minister) Kaggwa (in office: 1889-1926).

Drawing from a deep well of oral histories, which the author compiled from nearly 300 informants (72 principal informants), including royal wives and descendants, clan heads and leading ritual officers, the reader is treated to a wealth of information.

Kaggwa also gleaned valuable information from royal tombs, and historical relics, such as royal jawbones and umbilical cords, drums, weapons and fetishes. Each chapter is devoted to a king and chronicles the succession process, which was often fratricidal, the royal genealogies, wars, rituals and court intrigues. Prof Kiwanuka introduces this book with a well-argued justification for oral histories while also exposing the limitations of written sources. In doing so, he debunks theories posited by scribblers such as the explorer John Hanning Speke and missionaries like CT Wilson and RW Felkin, to name but three writers, who trace the Buganda royals to a “Hamitic invasion.”

This hypothesis is used to explain the presumed “genius” of the Baganda, claiming their royal house was helmed by Bahima. Prof Kiwanuka makes short work of this proposition by examining the social and political organisation of Buganda in relation to where Hamitic populations, such as the kingdoms Buganda and Nkore, predominate.

He goes on to uphold the merits of oral history in reflecting the popular memory by pointing how the Buganda’s methods of preserving its history through Kiganda traditions, the system of inheritance, and succession is almost airtight.

He further argues that the political and stability of the kingdom, being a sedentary and agricultural instead of migratory and pastoral, favoured the preservation of the past through lore. There were also designated offices to ensure such preservation.

“In pre-colonial Buganda, most of the non-administrative offices such as those of the guardians of the tombs, the jawbone and umbilical cords were usually hereditary in one clan and family. To holders of such offices, a biography (sic) knowledge of the kings whose jawbones they guarded was essential,” writes Prof Kiwanuka.

History lies in the eye of the beholder, so Prof Kiwanuka says that a proper assessment of Kaggwa’s historical writings cannot be done without understanding the man himself and his politics.

In Kaggwa’s day, Buganda was riven by a civil war that raged between 1888 and the early 1890s, fought in turns Christian and Muslim factions, before the former themselves split into Protestant and Catholic disputants. Kaggwa, a protestant, was on the winning side and this is partly why his histories carry the resonance of presumed truth. He starts off by relating the versions of the story of Kintu, which is essentially a creation story on a par with the biblical book of Genesis’s story about Adam and Eve.

Next, Kaggwa writes about Chwa I who also does a disappearing act as he vanishes into the annals of time. Kimera comes next and he takes the throne when he is fairly mature after having been brought up as a foster child. He meets a rather ignominious end.

It becomes apparent, as Kaggwa shares this history, why understanding him and his politics is deemed essential to this telling. That is because he paints a tableau of a society held in the throes of brutal kings, which Christianity supposedly rescued the kingdom from. Kabaka Ssuuna, for instance, had his own poison-maker called Kataba. “In the council meetings, all commoners had to look upon the floor. If anyone dared lift his eyes beyond the king and look upon the royal wives, that would be the end of him,” writes Kaggwa.

Again, Kabaka Mukaabya (which means the one who causes suffering) Muteesa (which means the statesman) lived up to his names in the tradition of Nominative determinism or the idea that your name can have some kind of impact in determining your job, profession, and even your character.

Muteesa’s penchant for blood sports and executions is bone-chilling, but his intellectual brilliance is also beyond comparison. He is the last Kabaka chronicled here before Kaggwa ends his narrative with Muteesa’s last premier, Mukasa.