Celebrating literary works of Gakwandi and Bukenya

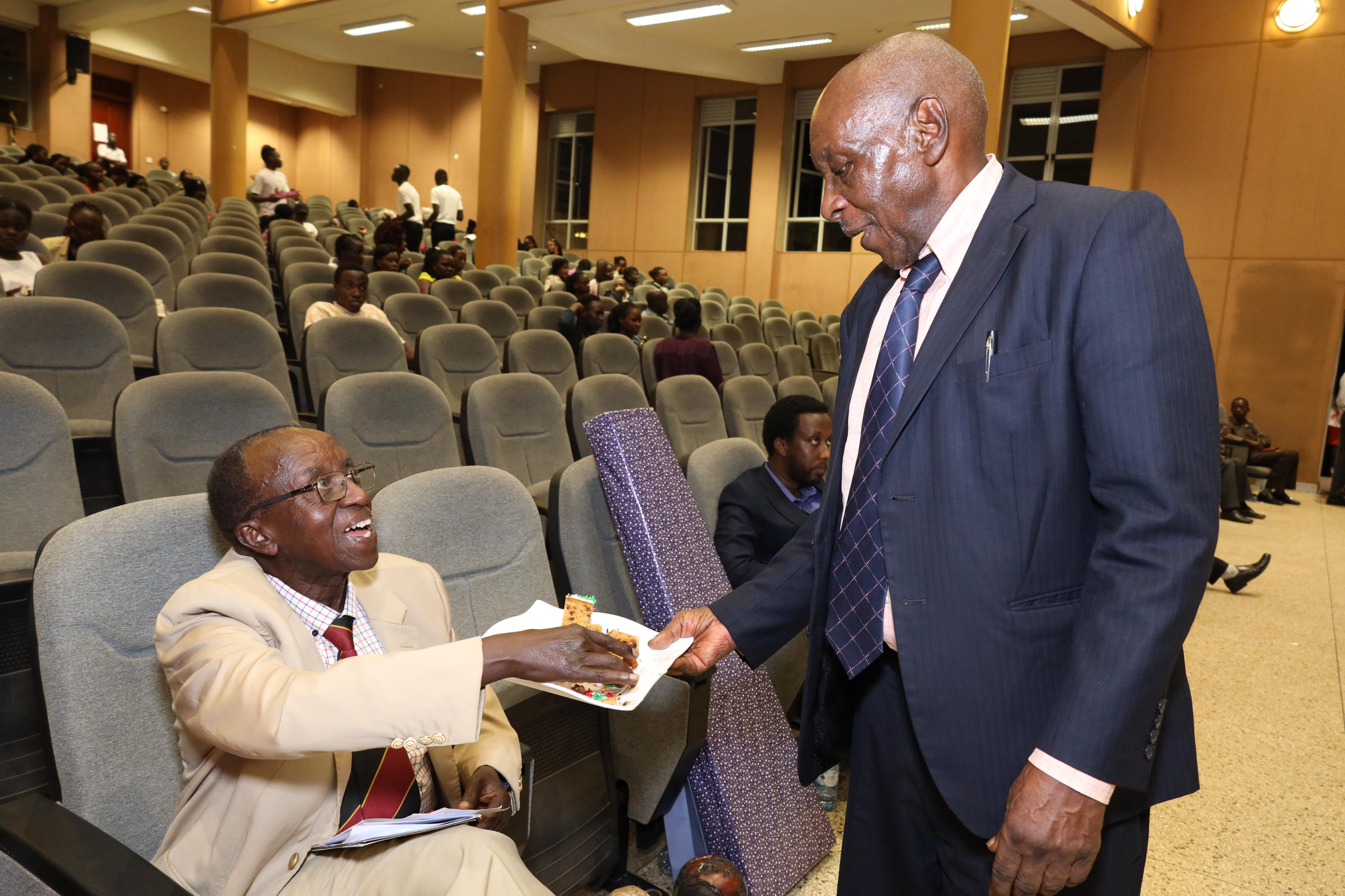

Prof Austin Bukenya serving a cake to Prof Arthur Gakwandi

What you need to know:

- Two literary luminaries turned 80 this year and their body of work seems just as limitless. Prof Austin Bukenya and Prof Arthur Gakwandi are pivotal writers, whose influence extends beyond borders.

When Makerere University opted to celebrate Prof Arthur Gakwandi and Prof Austin Bukenya on April 5, the performance of some of their literary works on stage was always a given. The literary luminaries turned 80 this year and their body of work seems just as limitless.

To celebrate their arrival on the eighth floor, presentations were culled out from Kosiya Kifefe, Prof Gakwandi’s novel; A Hole in the Sky, Prof Bukenya’s play; and Naturally, Prof Bukenya’s poem.

Prof Gakwandi’s novel is a chequered account of growing up in post-independence Africa, as profiled in the life and times of Kosiya Kifefe. Through Kosiya, the author traverses the years of the African youth with its dreams, uncertainties and escapades, while at the same time projecting images of a changing society that is rapidly disintegrating.

Kosiya was excited when he bought his first pair of shoes and stockings after selling agricultural produce. He immediately puts on the stockings and shoes, but he is uncomfortable because he has jiggers.

Consequently, Kosiya is disciplined at the school parade for not getting rid of the jiggers. His smelly feet are uncomfortable for his fellow pupils in the school dormitory.

In A Hole in the Sky, the search for oil by Tajeer and his overseas investor friends reduces Lake Riziki to a mass of black slime. It ruins the livelihoods of the many, who depend on the lake. Now Tajeer is mowing down forests and choking life-giving streams to clear land for a multi-million shilling project. Things begin to go haywire, when he attempts to evict Kibichi and his family from their ancestral land. Kijani, a fiery daughter of the family, will not let this happen without a fight.

Excellent body of work

With a veteran’s awesome mastery of language and dramatic technique, Prof Bukenya gives a rare poetic fusion of his passionate commitment to his dual subject matter—the environment and the courage of a “fierce, fearless, fiery fighter for all that is green and fresh and full of life.”

Prof Bukenya also addresses corruption, inefficiency and incompetence among government officials, as seen through the issuance of licences.

Tajeer develops cancer as a result of inhaling carcinogenic substances from the air. His modern medical doctor says the cancer is incurable.

Tajeer has always despised Kikongwe and his traditional herbal medicine. Ironically, it is Kikongwe, who applies his herbs to treat Tajeer’s cancerous tumours. It is the very herbs that Tajeer destroys to pave way for his jatropha plantation that Kikongwe uses to heal Tajeer.

Prof Bukenya’s poem, Naturally, is about the inability of the workers to understand the exploiter’s language and urges them to unite in order to fight for their rights. “…To break the bond, and I tell the workers to unite, knowing well they can’t see hear or understand:

What with sweat and grime sealing their ears

And eyes already blasted with welding sparks…,” the poem runs in part.

Transnational reach

According to Makerere University’s Department of Literature, Bukenya and Gakwandi are pivotal writers and literary scholars in Uganda’s history. Their influence extends beyond the country’s borders. Mwalimu Bukenya, as he is famously known, is a household literary name in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. He is acclaimed for his foundational work together with his teacher Pia Zirimu on orature, and particularly for coining the term that has proved fundamental in defining and developing the crucial field of African literature.

Prof Bukenya has been hailed as a strong symbol of the spirit of East African unity, having started at the University of Dar es Salaam. He graduated magna cum laude with a First Class degree and proceeded to teach in both Uganda and Kenya. He also developed textbooks on English language and literature courses for the region.

Prof Gakwandi’s foundational work, The Novel and Contemporary Experience in Africa, published in 1977, is still used as a reference to date. He is also known for his work as a diplomat that deeply understood and still understands the importance of national and global relationships, particularly in the context of the African continent.

Kosiya Kifefe has been on the Ugandan syllabus and is widely read in East African schools. He has taught at the University of Nairobi, Makerere University, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria, and Connecticut College, USA.

In esteemed company

The keynote address during the celebration lecture at Makerere University was delivered by Prof Abasi Kiyimba from the Makerere University Department of Literature. Titled Austin Bukenya and Arthur Gakwandi: Achievements, Contexts and Concerns, Prof Kiyimba underscored the fact that both subjects of his discussion are passionate about literature.

Kiyimba told his attentive audience the following texts were key for every student of African literature: G D Killam’s African Writers on African Writing (1973); Eustace Palmer’s An introduction to the African Novel (1972); Edred Jones’s The Writing of Wole Soyinka (1973); Chris L Wanjala’s (editor) Standpoints on African Literature (1973); and Ulli Biere’s The Origin of Life and Death: African Creation Myths (1966).

Austin Bukenya at 80.

Prof Gakwandi’s The Novel and Contemporary African Experience in Africa (1977) stands shoulder and shoulder with the key texts, per Prof Kiyimba. It was published in the same year that Byron Kawadwa was killed—presumably for writing the play Oluyimba Lwa Wankoko (Song of the Cock), an intriguing work that still refuses to fully surrender its secrets.

“The death of Byron Kawadwa had a chilling effect on both the practice and the development of Art in Uganda. Gakwandi’s work was one of those that helped to define direction for literature as a discipline, and to keep its fire going in the midst of the political turmoil of the 1970s and early 1980s that was decidedly hostile to the subject,” Prof Kiyimba disclosed.

“On the broader African scene, the work was one of those that commanded the waves of the African literary critical movement. It offered guidance on the way one could systematically study, evaluate, and interpret literature,” he adds.

Like Killam, Palmer, Wanjala, Jones and to some extent, Ulli Biere, before him, Prof Gakwandi dialogued with the African writers that had established themselves at that time. According to Prof Kiyimba, Chinua Achebe, Woe Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o (then James Ngugi), Ali Mazrui, Sembene Ousmane, Nadine Gordimer and others took part in the dialogue to establish the relationship between the novel and real life experience.

Octogenarians unplugged

Kosiya Kifefe came two decades after the publication of The Novel and Contemporary African Experience. Kiyimba describes the publication of Kosiya Kifefe as being similar to “the completion of a scholar-creative artist life cycle.”

“There is a sense in which it is a true contemporary experience, with Kosiya Kifefe starting from humble origins in an African village and rising to confront contemporary political realities… The author takes us through the years of the African youth with its dreams and uncertainties. At the same time, he projects the images of a rapidly disintegrating society as he takes the character through political intrigues and the lust for power and wealth,” he adds of the short story writer.

Prof Kiyimba likens Mwalimu Bukenya to Ngugi wa Thiongo “because he speaks and writes his mother tongue (Luganda), speaks and writes the East African regional language (Kiswahili) relish and his use of the international language and Ugandan language of education (English) is phenomena. In addition, he speaks French, and has also studied Latin.”

Prof Bukenya coined the term “Orature,” per Prof Kiyimba, “to capture the essence of African oral literary expression.” According to Kiyimba, before Prof Bukenya’s publication of Understanding Oral Literature (1994), Oral Literature Theory (1991), African Oral Literature for Schools (1983), studies of oral literature in English speaking Africa, were dominated by Ruth Finnegan’s oral literature in Africa.

“The work needed updating and supplementing with a native familiarity that Bukenya provided from their East African background and upbringing, with the publication of African Oral Literature for Schools in 1983. These achievements have given Bukenya an international platform,” Prof Kiyimba says of the 80 year old, who is also a published literary critic, poet and an accomplished stage and screen actor.

Bukenya’s novel The People’s Bachelor, which was published in 1972, satirises Africa’s new universities as misdirected and a wasteful irrelevance. Bukenya, who taught at ivory towers in the UK, Germany, and Madagascar, chastises the university elite—both students and lecturers—for engaging in distractions that are wasteful of the nation’s time and money. Prof Kiyimba, paper socialism and setting their target as paper qualifications that will not solve Africa’s problems.

“Austin Bukenya is humorous, but bitingly frank,” Kiyimba observes, adding, “He attacks the pretentious lifestyles of African campus intellectuals, especially when set against the harsh realities of the African surroundings. The academic pretensions are further marred by the grim descriptions of sexual exploitation of female students by their lecturers, whose amorous pursuits make them abandon the responsibility to protect.”

Second generation

According to Prof Kiyimba, both Gawandi and Bukenya deal with second generation issues—the pains and dilemmas of managing post-independence African societies. The first generation runs from 1956, when Sembene Ousumane first published in the white man’s language up to about 1970.

The other writers in this period are Chinua Achebe, Christopher Okigbo, Wole Soyinka, Kofi Awoonor, Ngugi wa Thiongo, Ama Ata Aidoo, and JP Clark, among others. The third generation in Prof Kiyimba’s loose periodisation that started in 2001 to-date, consists of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Doreen Baingana, and Jennifer Makumbi.

“…Knowing them (Bukenya and Gawandi) and having them as friends, being taught by them, and having them as colleagues, is an honour for which we shall always be grateful. May we live to be part of their celebrations at 90 and 100,” Kiyimba concludes.

In his acceptance speech Prof Bukenya warned against depending on Artificial Intelligence, saying it has the potential of wiping away the human race.