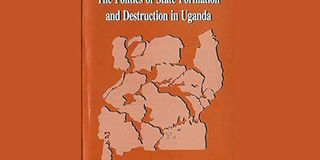

Title: The politics of state formation and destruction in Uganda

Author: Tarsis B Kabwegyere

Availability: Aristoc Bookshop

Pages: 259

Price: Shs20,000

Published: 1995

Colonialism did not express the civilising impulses of the colonialist. Instead, it revealed the socio-economic conditions in the West.

It is common knowledge that the colonialist exploited Africa to get at its natural and human resources. In order for this exploitation to proceed swimmingly, the colonialist needed to dominate their charges and keep them in isolation of each other. This impetus fashioned the intellectual underpinnings of the system of divide and rule.

The Politics of State Formation and Destruction in Uganda by Tarsis B Kabwegyere starts of by explaining Uganda (and Africa’s) non-colonial and colonial past as a primer demonstrating how this past is still very much in our present. As William Faulkner would say, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’

In order for the colonial state to be an effective instrument of oppression, it required to inflict violence on its colonial subjects. So it employed and unleashed three brands of violence to serve this purpose. This is physical, structured and psychic violence.

To distinguish between oppressive colonial regime, then, one required to analyze the degree of oppression rather essence or kind.

In Chapter Two, the author looks at the social organisation and political units in pre-colonial Uganda. He also, somewhat inevitably, charts the activity of the colonial government’s using constitutional arrangements to jibe with administrative convenience.

Bigger ethnic units had to be created where known previously existed in order to achieve this end.

“The Acholi study by Girling indicates that the household was the largest unit that could maintain a separate economic existence with a division of labour based on sex,” the author writes.

The methods used at different stages by the colonialists employed to acquire their colonial possessions was systematic and Buganda Kingdom, as this book ably expresses, was the springboard to colonial suzerainty in the whole of Uganda.

Chapter Four discusses the social structure and class stratification during the colonial period. The racial disparities led to animosities between Uganda’s colonial classes and widened further the elites-masses gap.

“The colonial social structure consisted of three social strata,” the author reveals. The top stratum was made up of the British colonial elite.

Asian immigrants were in the second tier of society. They dominated trade and commerce used to entrench and catalyze the smooth running of the colonial monetary economy. Although their economic power was not convertible to political power, they formed a powerful economic group called the “econocracy.”

“The Africans formed the third class, the dominated and exploited.