Prime

So, what will happen after Museveni leaves power?

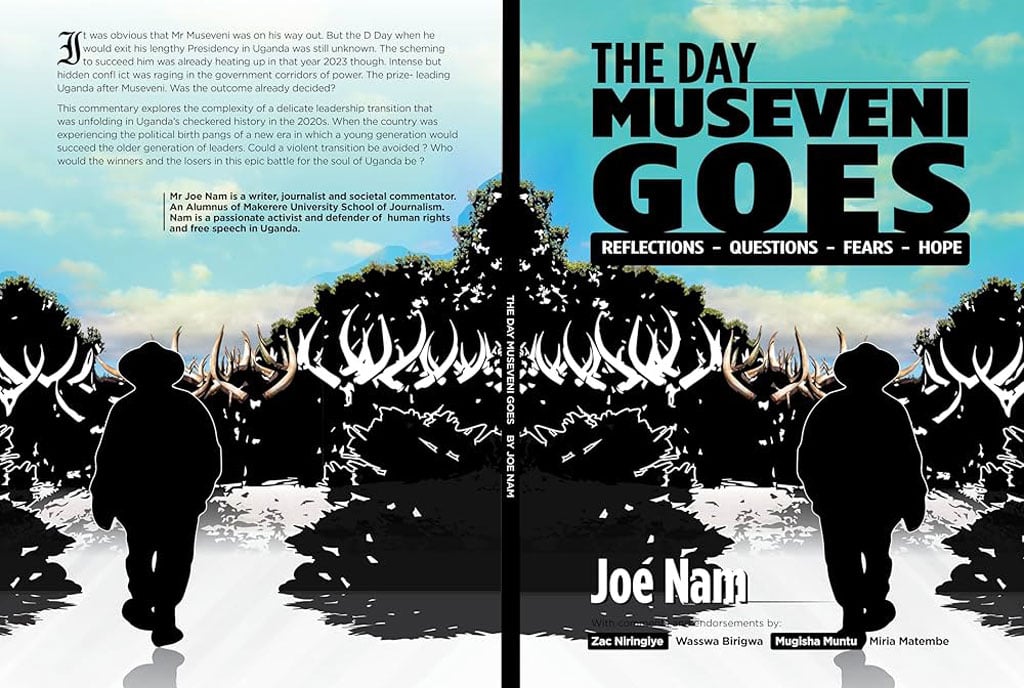

Book cover. PHOTO/COURTESY/AMAZON

What you need to know:

- The author, in spite of the political realties in the country, investigates possible scenarios after President Museveni leaves. Will VP Jessica Alupo swear in as President?

“It was obvious that Mr Museveni was on his way out. But the D-Day when he would exit his lengthy presidency in Uganda was still unknown. The scheming to succeed him was already heating up in that year 2023 though. Intense but hidden conflict was raging in the government corridors of power. The prize---leading Uganda after Museveni. Was the outcome already decided?”

This is how the new book titled The Day Museveni Goes: Reflections, Questions, Fears, Hopes by journalist Joe Nam opens its account. Although there have been several books on Museveni and his presidency, I do not think there is a book out there on a post-Museveni Uganda that reads this effortlessly.

In praise of the book, Maj Gen Mugisha Muntu, Ambassador Wasswa Birigwa, Bishop Dr Zac Niringiye and the irrepressible Miria Matembe largely agree.

It is agreed Mr Museveni must lead the charge to a post-Museveni Uganda. He has created an edifice of patronage that will not have it any other way. That is because he is the alpha, the omega and all the political trimmings that come with the two.

ALSO READ: Museveni: Old man of the State

As Matembe says in this highly readable book, “I am now living a quiet life, but if I were to declare that I will run for President in 2026, you would see how I would get dragged in the mud. But if everyone left Museveni to run for President alone, he would still hire some people to stand against him, to legitimise the process. We do not have elections in Uganda these days, what we have is voter purchase.”

The author, although utterly objective, agrees with Matembe. In doing so, he takes us back to the beginning, when Mr. Museveni was born. Then sketches a way forth.

In Chapter 2, A Country In Transition Season, he writes: “Museveni would be bestowed the honour of elder statesman. Mr Museveni would then join the revered company of senior African leaders, who voluntarily or constitutionally stepped down from office. That company comprised; Nelson Mandela-South Africa, Julius Nyerere-Tanzania, Sam Nujoma—Namibia, Joachim Chissano-Mozambique, Eduardo Dos Santos—Angola, Pierre Nkurunziza—Burundi, Uhuru Kenyatta-Kenya and a few others.”

Such esteemed company. As it stands, however, Mr Museveni belongs to a rogues’ gallery instead, where leaders such as Cameroon's 91-year-old President Paul Biya are prominently on display.

ALSO READ: Did Friday 13th bring Museveni to power?

The author, in spite of the political realties in the country, investigates possible scenarios after Mr Museveni leaves. One of these scenarios might have our very own Jessica Alupo swearing in as President and giving a speech similar to the President of Tanzania Samia Suluhu’s speech, upon ascension to the presidency.

“For those who are doubtful whether I can be President of Tanzania, I want to tell them that the person standing here is President of the Republic of Tanzania, I want to repeat that the person standing in front of you is the President of Tanzania whose anatomy is female.”

It would be nice to hear Alupo assure a nation gripped by uncertainty after Mr. Museveni inevitably leaves. Of course, Ugandans have every right to feel apprehensive about this.

Mr Museveni has dominated our politics with unrelenting intent since 1986 and this has left obstacles in the way of any would-be Museveni successor.

“The NRM of the 1986 and the NRM now are not the same. If the two were to meet, they wouldn’t recognize each other. There are many things that as pioneers we believed in and held dear but have now changed. You find profiteers and all sorts of characters including criminals in the NRM,” the author quotes Maj. Gen. Kahinda Otafiire as saying.

Against this background, the author’s assumption that there will be a Uganda worthy of the appellation “country” after Museveni goes is optimistic, indeed.