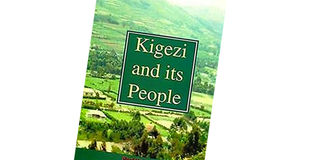

Title: Kigezi and its People

Author: Paul Ngologoza

Price: Shs20,000

Availability: Aristoc Bookshop

Pages: 148

Reprinted in 2021

Philip Matogo

While many Kigezi people copied the Baganda, adopted their dress, their diet, their religions and their administrative methods, they resented Kiganda pretensions and resisted Luganda as a language.

The 1975 book A History of Kigezi in South-West Uganda by Donald Denoon is an authoritative book on Kigezi region.

It was previously considered the best written book on Kigezi District. But that is only because those who have read Kigezi and its People by Paul Ngologoza did not take that rather informal poll.

Although both books are possessed of the literary merits that make up classics, Ngologoza’s is more of a reader’s digest for those who want to know about Kigezi through the eyes of a scion of southwestern Uganda.

Indeed Ngologoza’s book is a translation of the original work Kigezi n’ Abantu Baamwo, which was first published in 1967. The book traces the origins of the people of Kigezi, their customs and traditions, the part played by the British and their Baganda agents in Kigezi and the coming of Christian and Muslim missionaries.

Kigezi District once covered what are now Kabale District, Kanungu District, Kisoro District and Rukungiri District, in southwestern Uganda. There were already some Bakiga in Kigezi in 1,500, the author writes. Evidence of their presence was betokened by the fact that in that year the King of Rwanda, Yuhi II Gahiima, was waging war against them.

Before Kigezi was known as Kigezi, it was known by the following names: Mundorwa, or Munkiga of the Bakiga or Rukiga, which now comprises three sazas---Rukiga, Ndorwa and Rubanda. Originally, the author tells us, there were three major tribes in Kigezi. These tribes are the Bakiga, Bahororo and Banyarwanda. The minor ones were the Banyabutumbi, Bahunde and Batwa.

Before the coming of Christianity to Kigezi, the region observed certain customs. For example, the mother’s milk was considered taboo. “It is said that a husband and wife fought while she was still breastfeeding her baby. The wife left her child and ran away to another clan, where she stayed for a night,” writes Ngologoza.

“It is said, that she was accused of having an affair and hence the ‘killing of the baby’s milk.’ When she returned to her husband, a large door-bar was placed at the gate of the enclosure, on which she could sit and suckle, and this signified the end of the taboo.

But the real purpose of the procedure was to warn breastfeeding mothers not to abandon the babies, while running away from their husbands, as the babies would be a problem to fathers. The taboo was a warning to women not to have extramarital affairs.”

As Christianity spread and colonialism took hold, there were other age-old traditions that were challenged or voluntarily altered. Since the British used Buganda as a sub-imperialist to help colonise the whole of what later become known as Uganda, Baganda colonial administrators came to Kigezi. “While many Kigezi people copied the Baganda, adopted their dress, their diet, their religions and their administrative methods, they resented Kiganda pretensions and resisted Luganda as a language,” says the author.

“What was intended was to retain a Kiganda system, but to localise its personnel, in much the same way as independent governments have retained the methods of colonial rule, but Africanised the posts.” This happened as Bakiga got to grips with the centralised bureaucratic regime of Kiganda administration. This system of rule was at odds with the pre-colonial Kiga system of administration which was decentralized.

It is true that the people of Kigezi did not trouble the British the way, say, Bunyoro kingdom did. But there were rumblings of dissent as seen during Nyabingi Resistance/Movement in August 1917.