Hilda Victoria Namulwana feeds her birds three times a day. Photos | Abdul Nasser Ssemugabi

Fresh from studying Tourism and Hospitality Management at Makerere University in 2023, Hilda Victoria Namulwana worked with a tour company, earning Shs1.2m a month—but only for two months. After five months without pay, she quit and reverted to poultry farming, a job she grew up doing. Seven months later, the 26-year-old 2023 Miss Heritage Buganda has no regrets.

It’s a family thing

Poultry is a culture in Namulwana’s family. Her grandmother, who lives with the family, started it decades ago at her home in Mugalu Zone, Mpererwe, off Gayaza Road. Years later, she retired leaving the structures idle. Later, her daughter-in-law, Namulwana’s mother, revived the trade, rearing commercial layers as her husband supplied the feed.

Namulwana grew up seeing chicken. From her salary in A-Level vacation, she expanded the chicken house. She picked eggs and fed the chicken every morning before going to university.

Business was booming. She delivered eggs to nearby shops, daily. Then Covid-19 came. Feed became scarce and expensive yet prices of eggs fell drastically. Keeping 1,200 birds became unviable. “We started selling them off in bits and soon they were all gone.”

Last October, three years after that Covid-19 induced setback, Namulwana resurrected the business with 100 broilers.

Her batch of 500 broilers also has 22 Sasso chicks for her little sister Gabriella Nalule. “We used her piggy bank savings to instill a business spirit in her,” Namulwana said.

That is Nalule’s second batch. The first one was a hit, each chicken sold at Shs50,000 after just three months. She does not buy feeds. But the 10-year-old must attend to the entire flock every Sunday when she’s not at school. And she loves it. In the next three months, she will be a million shillings richer.

Wondering how Namulwana juggles poultry and tourism gigs that require miles and days away?

Her mother and sisters chip in. When a potential buyer contacted her online, she was away and referred him to her mother, who sealed the deal that cleared her recent batch of 300.

Her father is equally supportive. The seasoned agrarian knows that feed takes the majority of a poultry farmer’s budget. He stocked four tonnes of maize from his ranch. Namulwana will pay in installments.

It’s a cycle. The ranch feeds the chickens. The chickens return the favour in form of manure to enrich the ranch, which also yields food and money to the family.

Basics

The gist of broiler business is fattening your chicken in a few weeks for meat. So monitoring weight gain is paramount. Ordinary farmers use eyes and hands. Namulwana is scientific. She bought a weighing scale. “On day one, a chick must weigh about 36 grammes.” After a week, they hit 216 grammes. She repeats at two weeks, then after that, every three days. At four weeks, the chicken must be 1.5 kilogrammes, ready for sale.

It is okay if one or two chicks die. But besides vaccination, Namulwana stocks vitamins to boost the chicks’ immunity and antibiotics in case of common infections like coccidiosis and cough, “because your vet may not help.”

She warns that you avoid the chicken coop when you have a cough or flu. “Or wear a face mask.”

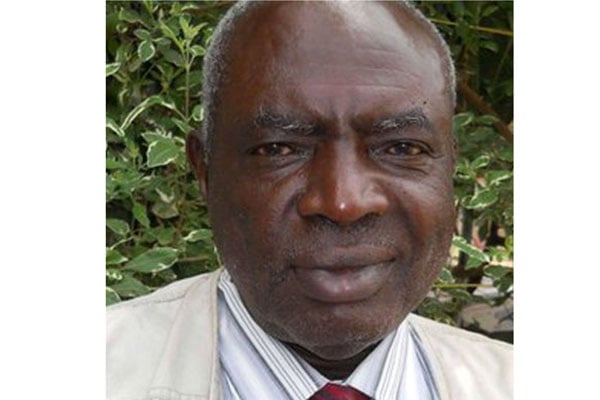

Hilda Victoria Namulwana

Temperature and hygiene are also vital to health and growth. From day one, Namulwana’s brooder had three pots of burning charcoal and a stove with a honeycomb briquette.

The pots have holes in the neck to burn efficiently. She refills them whenever the charcoal levels reduce to keep the temperatures steady (between 29°C to 36°C) for the chicks to enjoy. She does this for about two weeks because her home is cold due to the forest-like environment. (She once used heat lamps but they often blew out. Plus, power outages.)

From day one, Namulwana covered a white paper carpet over coffee husks in the brooder so that the chicks do not mistake husks for feed.

But on June 16—their sixth day—she removed the carpet. The chicks were now wise enough to see the feed.

She raised the feeders and drinkers on bricks so that as the chicks scratch and bathe on the floor, the husks don’t spoil the feed and the water. The chicks will also not waste the feed by scratching it into the husks.

Be sure about feeds

Namulwana started her chicks on quality pellets of broiler starter feed from a reputable Dutch company. On June 18—their eighth day—she introduced them to maize and concentrate. She mixes 120kg of maize with 50kg of concentrate, a new brand from the Netherlands. There, she avoids using soy cake, silverfish, cotton, snail shells—cheaper but sometimes substandard.

Know your supplier

Before choosing your chick supplier, seek genuine advice from farmers and vets. Namulwana’s first batches, from a major supplier that has operated since 2014, were successful. But the two lots from a supplier near home were terrible.

The chicks grew annoyingly slow, despite good feeding. “The second batch suffered cough from the start to the end. No amount of drugs could help.”

Namulwana later learnt that the supplier sold poor-breed chicks from her inferior hatchery packed in boxes with labels of reputable breeders. Namulwana found a genuine supplier.

Namulwana says moderate heat is paramount in the brooder.

But even big-name breeders can connive with fraudsters. My friend booked 500 chicks from a reputable supplier. He got 300 in the morning. But in the afternoon, he was called to pick up the 200.

He wasn’t suspicious but soon realised a big number of the chicks growing very slowly.

He struggled with them, bought more feed, but still sold them at a loss until the seventh week.

“Had I known they were a poor breed, I wouldn’t have spent more on feeds,” he regretted. He is still recovering from the losses, but he learnt his lesson.

Marketing, profit

Do not expect profit from your first 100 broilers, because chances are you are spending on almost every input.

But subsequent batches must get you a profit. Namulwana said she spends Shs9,000 on each chicken in four weeks when it’s ready for sale. So, selling each at Shs11,000 to Shs13,000 guarantees a profit.

But where’s the market? “Everywhere,” Namulwana believes. When she recently advertised her chickens on X, formerly Twitter, the person, who bought off all the 300 instantly—each at Shs12,000—at first didn’t even seem very serious.

Now, that one has joined her growing clientele. “We keep in contact with all our customers. Anytime we call them.”

Her friend in Kawuku, some miles off Entebbe Road, wondered where she could sell her first batch, moreover offseason. Namulwana allayed her fears. “When her 200 chickens were ready, I told her to take photos of them and approach guys who roast chicken in Kawuku town. She sold out there and then.”

Namulwana connects others to buyers and offers free online advice. “We can’t exhaust the chicken market because people eat chicken every day.”

Why broilers?

Namulwana started with 100 broilers in October 2023, then 200, 250, now 500. Next October she is targeting 1000 plus 200 layers. Part of the profit will roof her parent’s 10-bedroom round house by December.

“Our parents sacrificed for our wellbeing. I feel indebted to give back.” Namulwana was more familiar with layers but did not need extra skills for broilers because brooding basics are the same, for all breeds.

She also chose broilers which require less capital and yield quick income. For example, 100 broilers cost you Shs900,000 in four weeks, but 200 layers require Shs4m until the sixth month, when they drop the first egg.

Multi-tasking

Rearing chickens did not stop her other errands. When at home Namulwana writes articles on tourism and conservation for tour companies.

In the field, she does nature photography and birding— a lucrative venture.

The director of women in conservation at Herp Fauna Foundation recently founded Tribe 56— which specialises in cultural tourism. She works with Traditional Medicine In Transition—a joint project by the Uganda Museum, Makerere University, and the University of Zurich.

Namulwana believes these connections will enhance her tour company and farming, which she plans to do forever.

She dreams of a five-acre model farm with poultry, coffee, bananas, fruits, cottages, and restaurants for her tourists, where students can also do internship.