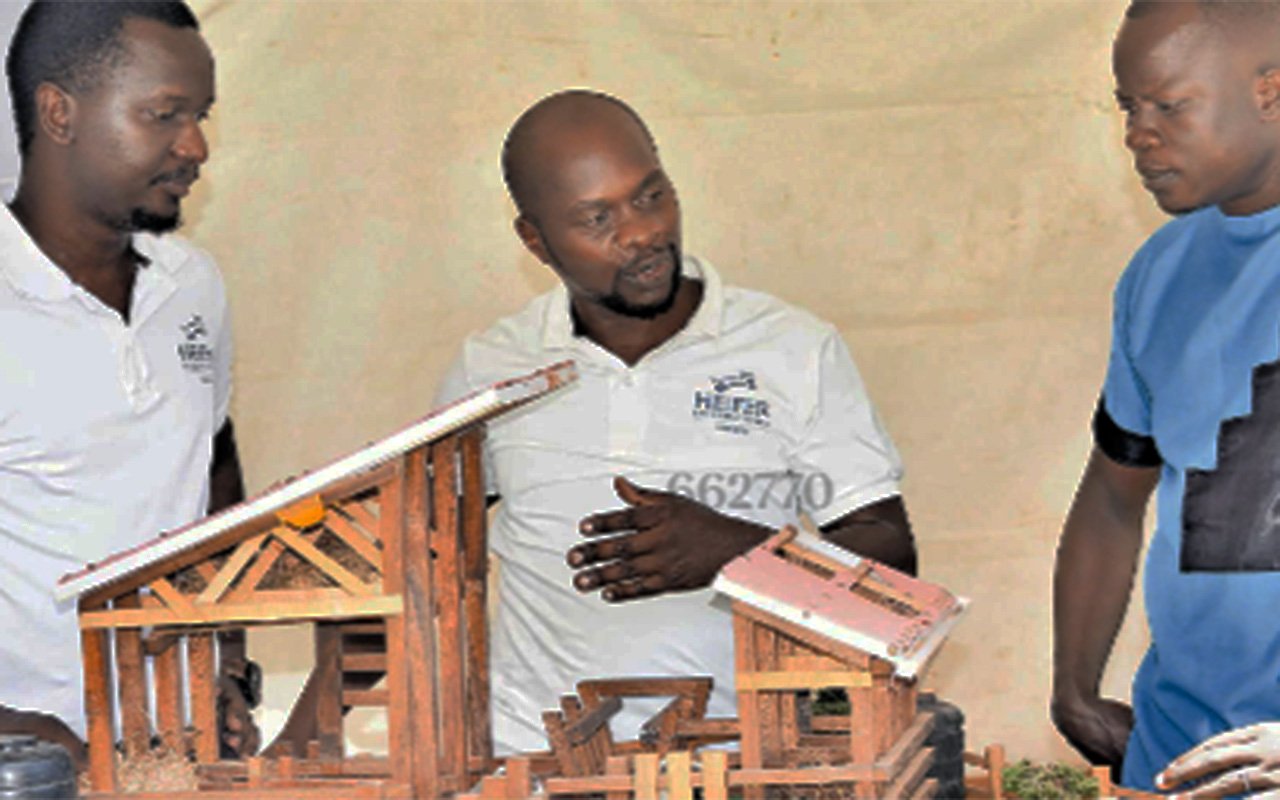

One of the indigenous goat breeds. Small body, rich taste. PHOTO/ABDUL-NASSER SSEMUGABI

Indigenous and traditional food systems have served as a major source of healthy diet that ensures food and nutrition security. Access to secure, nutritious, and healthy food is one of the aspects offering greater human security and societal stability.

Every house needs food but safe food is important if it has been grown, prepared and transported agro-ecologically.

The 2024 National Population and Housing Census shows only 54 percent of households in the country are food secure, while 31 percent are experiencing severe food insecurity, and 46 percent moderately or severely food insecure. As Uganda faces the dual challenges of climate change and food security, the spotlight is shifting towards indigenous foods as a solution for sustainable agriculture. These traditional crops, once staples in Ugandan diets, are now at risk of fading into obscurity.

Uganda is endowed with a lot of indigenous and traditional foods. Bananas for instance were introduced from South America but were customised into the Ugandan cultures and many people eat them as their staple food.

Historically, these foods were integral to local diets, providing essential nutrients and supporting cultural practices. However, with the rise of monoculture farming and Western dietary influences, the cultivation and consumption of these indigenous crops have dramatically declined.

Current statistics reveal a troubling trend according to Francis Nsanga the Project Manager, Knowledge Centre for Organic Agriculture (KCOA): Many farmers have shifted towards high-yielding, hybrid varieties that often lack the nutritional diversity found in indigenous crops. As a result, traditional knowledge surrounding these foods is waning, threatening not only agricultural diversity but also food sovereignty.

Despite their critical importance, the food systems, crops and knowledge systems of Indigenous and traditional peoples are often perceived as “backward” or unproductive and are threatened by the industrialisation of agriculture and food, economic development and globalisation, leading to widespread losses of food-related biocultural diversity in many countries (FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021).

“The modernisation of agri-food systems has helped reduce undernutrition,” Nsanga says.

Modern application

The indigenous foods are usually safe from chemicals and toxins and are highly nutritious compared to the improved varieties. According to research, the indigenous foods contain better nutrients that play a vital role in boosting the immune system.

For example, the indigenous type of yams can grow anywhere and not need a lot of water like the improved yam. The latter require water logged places like swamps which are usually deposits of industrial purification of chemicals and wastes.

Josephine Akia Luyimbazi, the country coordinator at PELUM Uganda says, “Many times the improved varieties of yams are found to have residues of metals that are not safe for human consumption because they increase the risk of cancer.”

When it comes to chicken, Luyimbazi notes that many of the improved varieties, layers or broilers are injected with hormones to quicken their maturity. “The consumption of hormone-boosted chicken raises concerns about potential health impacts on humans, which can indirectly affect the ecosystem through changes in health and dietary practices.”

The indigenous breeds on the other side are tastier, healthier and safer because they are usually resistant to diseases and do not need vaccination or use of antibiotics to boost their immune system. The rate of non-communicable diseases in Uganda is as high as 33 percent and this is also a global health concern according to Luyimbazi, there is a need to replace fast foods with indigenous foods in order to curb down such diseases.

The need for diversity

Indigenous and traditional food systems have served as a major source of healthy diet amongst the local communities.

These food systems represent a treasure of knowledge that contributes to well-being and health, benefiting communities, preserving a rich biodiversity, and providing nutritious food.

Asked about the profitability of indigenous foods, Luyimbazi noted that there is a big market for these foods but there is a need for value addition. “It is important that farmers become enterprising by growing a number of different food varieties and livestock that have different gestation periods. With this, the farmer will be able to have food stuff for sale throughout the year and not only look at one particular item for sale.”

She also remarks that if farmers diversify as much as possible, there will be enough food supply and this will ensure food security to families and homes throughout the year.

In a world where the effects of climate change are very devastating and a decline of soil fertility is very evident, Luyimbazi notes that there is need for use of fertilisers, “but we can use for compost manure, agricultural waste, grow beans to fix nitrogen in the soil or charcoal for phosphorus. There are many organic fixes that do not affect the ecosystem,” she says.

Challenges

Despite the clear advantages, the road to revival is fraught with challenges. One of the primary obstacles is the limited availability of seeds for indigenous varieties.

Many local farmers lack access to quality seeds, which hinders their ability to cultivate traditional crops. Additionally, there is a significant gap in knowledge regarding indigenous agricultural practices, as younger generations move away from farming or adopt modern techniques.

“We do not have enabling policies. We have a draft of the national agro-ecology policy that we think once put in place would help preserve the indigenous foods and could help in improving food security,” Luyimbazi says.

Financial constraints also pose a significant barrier. Many smallholder farmers lack the resources needed to experiment with indigenous crops, fearing economic loss if their efforts do not yield sufficient returns.

The way out

To combat these challenges, several organisations, including PELUM Uganda, are working to promote the revival of indigenous foods. Their initiatives focus on education, community engagement, and the establishment of seed banks to ensure the availability of indigenous seeds.

Workshops and training programs aim to equip farmers with the skills and knowledge necessary to cultivate these crops sustainably. “Community-led initiatives, such as local food festivals, are also gaining momentum, showcasing the culinary potential of indigenous foods and fostering pride in local heritage,” Nsanga says.

As Uganda seeks to bolster its food security and sustainable agricultural practices, the revival of indigenous foods emerges as a crucial strategy. By addressing the challenges of seed availability, knowledge gaps, and market demand, Uganda can pave the way for a more resilient and diverse agricultural landscape.

The journey to revive indigenous foods is not just about reclaiming lost culinary traditions; it is about ensuring a sustainable future for Uganda’s agricultural sector. With concerted efforts from communities, organisations, and policymakers, the rich tapestry of Uganda’s indigenous foods can flourish once again, nourishing both the land and its people.

Modern application

The indigenous foods are usually safe from chemicals and toxins and are highly nutritious compared to the improved varieties. According to research, the indigenous foods contain better nutrients that play a vital role in boosting the immune system.