Prime

Akello, 62, illuminates lives of lepers

Simporoza Akello, a leper is empowering other lepers and persons with disabilities with skills to be self-reliant.

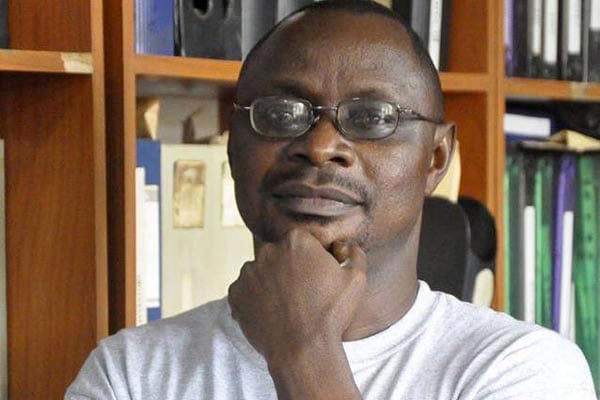

PHOTOS BY TOBBIAS JOLLY OWINY

What you need to know:

- Akello Simporoza empowers lepers with skills to be self-reliant.

- What stands out, each of the learners has hope to change their destiny.

It is exactly 3:41pm and Consolata Apio nibbles on the lid of a pen gripped tightly in between two deformed arms, as she fidgets to explain how she got seven after multiplying two by three.

Apio, 58, a leper and a beggar who has been living a solitude life and surviving on the streets of Lira Town is one of Simporoza Akello’s 31 students.

At the corner of the room, sits Akello, 62, who is the class monitor and instructor. She recovered from leprosy 11 years ago, although the infection had eaten parts of her four limbs.

She teaches other lepers and persons with disabilities how to read and write and the basics of the local language. Akello takes the learners through basic mathematics, reading, writing and life skills every Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays.

In her class of Obanga-oribowa Learning Centre that sits at the maternal health unit of Lira Referral Hospital in Adyel division, there is a total of 31 students, who all suffer from leprosy.

Akello envisions a day when lepers will leave the streets and stop begging. This is the reason she works so tirelessly to empower lepers with knowledge and skills on how to be self-reliant.

“I want lepers to live a better life as opposed to street begging that has seen many stigmatized,’’ Akello says.

She says apart from teaching, she was offered an open space at Lira Regional Referral Hospital, where she has planted vegetables. This serves as a demonstration farm, where learners are taught how to grow crops and raise money from backyard gardening.

The class of lepers

Although she did not go far in education, Akello says being a beggar was another class that taught her tough lessons. She recalls the abuse and hatred she was subjected to everyday on the streets.

Her turning point was May 2014, when a friend, who frequently dropped for her coins, convinced her to join him for prayers at All Nations Church. This is where Hands across Nations, a local NGO in Lira town enrolled her for reading and writing classes together with other elders.

After learning how to read and write, Akello’s life was never the same again. “I have stopped feeling sorry for myself and wallowing in self-pity. Despite the rejection, hatred and stigma I faced from the community, I discovered that I had the power to turn my life around for the better,” she says.

Akello says she felt it was time to mobilise other lepers to form a class and change their lives. She, however, says it took her lot of time to mobilise lepers from the streets and she met a lot of resistance. “They felt abandoned, rejected and preferred to live in isolation. They survived through begging,” she says.

With only three learners at the start of 2018, Akello’s class had expanded to 28 by the end of 2019. In her class, 17 learners have deformed limbs although they struggle to read the local language and common words as well as do simple calculations.

What stands out, each of the learners has hope to change their destiny.

Patrick Okello, one of the learners says he can read the bible, in which he finds solace. He says he has learnt to love himself and has hope of living a better life, despite the fact that he has spent 23 years on the streets as a beggar.

Leprosy is a chronic, progressive bacterial infection caused by the bacterium mycobacterium leprae that primarily affects the nerves of the extremities, the lining of the nose, and the upper respiratory tract.

It is one of the diseases recorded in history, according to the World Health Organisation dating back to 600 B.C. It produces skin sores, nerve damage, and weakness of the muscles. If it is not treated, it can cause severe deformity and significant disability.

Carolyn Jones, the director for Hands across Nations says the organisation is committing more resources in rehabilitating the lives of the physically handicapped and rejected members of the society within Lira district.

“They have learnt communication skills and this step alone is key in making them very useful members of society. Every human counts irrespective of their physical state. They can support each other now,” says Jones.

Illness and barrenness

When Akello met her first love on a market day in Amwoma village, now Dokolo District, a week before former President Iddi Amin claimed power in 1971, all was well until she failed to conceive for her husband.

The failed conception which she attributed to what she later confirmed as barrenness cost her marriage when she was forced by the husband to pack her bags and leave his house.

“When I returned to my parents’ house, I was ill for a month and I started developing complications. After several tests and diagnosis, I was told I had leprosy,” she says.

She says her family decided to take her to Alito Lepers’ Village, a rehabilitation centre for lepers in Kole District since leprosy was contagious.

“For 18 years, I lived a life of rejection. I had lost all my toes and fingers because of the infection. But in 1991 I left the centre,” she said.

In 2,000, Akello and her relatives were forced by the Lord Resistance Rebel Army (LRA) to live at a camp in Lira Town upon fleeing their village.

Hurdles she meets

Akello is among the beneficiaries of a learning programme of Hands across Nations that has since 2014 been enrolling destitute and disabled persons for bible studies as well as teaching them how to read and write.

She, however, says there are several challenges that she counts to be hindering her efforts such as accommodation and settlement. She says some of the lepers in her class end up going back to the streets because they expect to be accommodated.

Akello’s class involves learners who are difficult to tame. She says the public stigmatise lepers and are regarded as people of no value in society.

She says despite the money she earns from her efforts in equipping lepers with basic life skills, it is more rewarding to make a positive impact in the lives of those whom the world forgot about.

“Learners in my class can read signposts and directions whenever they are in a congested town. These skills have reignited hope and self-esteem in all of us. I am now loved by friends and I feel so confident in public nowadays,” she added.

Akello hopes to free Lira Town of lepers who beg on the streets. She says once she gets a means of transport such as a bicycle, she will embark on outreach programmes to visit, monitor and counsel lepers who do not attend classes regularly.

Low burden

Dr Stavia Turyahabwe, the assistant commissioner National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Division at Ministry of Health Ministry says leprosy burden in the country has drastically gone down and that many isolation centres have since been closed.

She says Buluba Hospital in Mayuge District remains the only active health facility, where active leprosy cases are isolated and treated.

“The disease was eliminated as a public health threat in 2004 and the prevalence rate has since reduced to a ratio of 1:1million people, prompting us to close down almost all these isolation facilities across the country,” says Dr Turyahabwe.

She noted that every year, Uganda records less than 200 active leprosy cases.

Journey

I had power to turn my life around

After learning how to read and write, Akello’s life was never the same again. “I have stopped feeling sorry for myself and wallowing in self-pity. Despite the rejection, hatred and stigma I faced from the community, I discovered that I had the power to turn my life around for the better,” she says.

Akello says she felt it was time to mobilise other lepers to form a class and change their lives. She, however, says it took her lot of time to mobilise lepers from the streets and she met a lot of resistance. “They felt abandoned, rejected and preferred to live in isolation. They survived through begging,” she says.

With only three learners at the start of 2018, Akello’s class had expanded to 28 by the end of 2019. In her class, 17 learners have deformed limbs although they struggle to read the local language and common words as well as do simple calculations.

What stands out, each of the learners has hope to change their destiny.