Prime

How Covid-19 is affecting reproductive health efforts

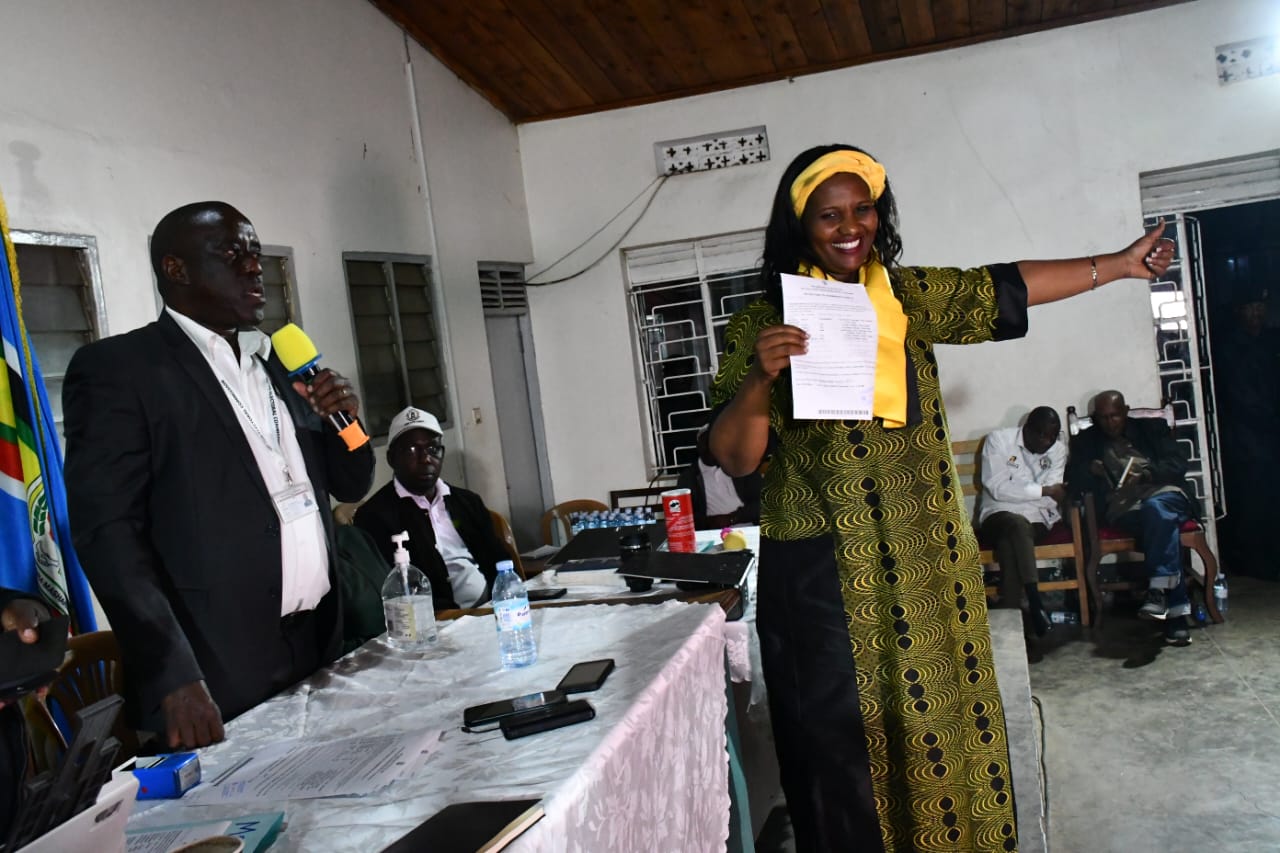

Pregnant women sit at the veranda of Lira RDC’s office as they wait patiently for temporary travel permit on March 3, 2020. PHOTO BY ISAAC OTWII

What you need to know:

baby boom. In an effort to combat Covid-19, most health facilities have shifted attention to Covid-19 patients. Many expectant mothers have missed out on antenatal care services and those who want family planning services cannot access them. Some health centres have run out of contraceptives and experts warn that Uganda may witness a rise in unwanted pregnancies in the near future, writes Gillian Nantume.

You do not need to look too far to find the strain of the lockdown. It is plain to see, especially on the face of a pregnant woman. So far, the national response to Covid-19 has been blind to the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs of youths and women.

Last week, during my afternoon run, I bumped into Brenda Auma at the Muzinga Square Park in Entebbe. Heavily pregnant with her second child, she trudged slowly from Kiwafu Central village on her way to Stanbic Bank branch in Entebbe town – a distance of three kilometers.

With a seven months pregnancy, and almost no antenatal care, Auma is keeping her husband’s money close to her.

“On March 26, I went for routine antenatal at Entebbe Hospital, but there was no midwife to attend to us. We were five of us. The askari (security guard) told me to come back after the lockdown was lifted. I went back last Monday, and a nurse confirmed to me that antenatal services had been suspended at the facility,” she says.

Auma got the same response from Dr Ronald Bata Memorial Hospital on Nsamizi Hill. Being a military hospital, it has 60 nurses, five general doctors and 12 clinical officers. But, the antenatal clinic is closed.

“A nurse told me to return after a few weeks. I don’t know what to do now because I am missing antenatal services. I have thought of going to a private hospital but I fear it might be too expensive,” she says.

In his address last Sunday, the president permitted pregnant women, who are due to deliver to use any means of transport to reach health centres. However, those who are not in labour, like Stella Kagere, an insurance worker, have been left out of the loop.

“I have been attending an antenatal clinic at a private health facility. But, last week when I called to set up an appointment with my gynaecologist, he discouraged me. He was uncomfortable running the clinic,” she says.

Even though health services are essential, when the count is finally made, some women will have lost lives due to the priority placed on Covid-19.

Two weeks ago, on April 6, a woman died at an isolation centre in Koboko District, from the effects of a miscarriage. When she felt ill at her home in Arabanga village, in Degimba Parish, the locals had handed her over to the district surveillance team, as a suspected Covid-19 case.

Dr Denis Oloya, the acting district health officer, says in a pandemic, nothing can be taken for granted.

“If you have a high fever, cough and a sore throat, we must investigate. It was unfortunate that she passed on. She had not been taking proper medication (for the miscarriage) and nothing was known about her medical history. She was brought in on Saturday evening, and died on Sunday morning before the health workers could attend to her."

When the results finally came back, the woman had tested negative for coronavirus. Dr Livingstone Makanga, the assistant commissioner for Reproductive and Infant Health at the Ministry of Health (MoH), says he would be hard pressed to blame medical personnel.

“It is true that some women are being turned away from antenatal services, but Covid-19 is a real threat, even to health workers. In the beginning, there was a lot of fear, but now the ministry is sensitising district taskforces and coming up with guidelines for health workers,” he says.

Dr Makanga admits that even though health workers are having challenges with protective gear, a broader intervention – that includes offering them psychosocial support – is needed.

Family planning abandoned

In 2014, MoH launched the Costed Implementation Plan (CIP) to reduce the unmet need for family planning, and increase the modern contraceptive prevalence rate among married women to 50 per cent by 2020. The CIP was to ensure that by 2020, Uganda will have averted more than four million unintended pregnancies, five hundred thousand abortions, and six thousand maternal deaths.

A Performance Monitoring and Accountability (PMA 2020) survey, led by Makerere University School of Public Health, found out that in 2018, contraceptive uptake is up to 41.8 per cent among married women. However, the survey, conducted in 78 districts, also found that 46.2 per cent of pregnancies were unintended.

The ban on transportation and gatherings, while good for preventing the spread of the coronavirus, threatens to reverse the gains Uganda has made in the use of modern contraceptives. In rural areas, where people cannot walk long distances to the health centers, non-governmental organisations have been conducting medical outreach programmes, where they give out relevant SRH information and contraceptives, free-of-charge.

Steven Karamuzi, an SRH service provider in Mbarara District, says most of his clients have been using bodaboda to transport them to the clinic.

“We have seen a sharp decline in women seeking SRH services, especially family planning. People will rarely walk five kilometers or more to get contraceptives. Family planning is definitely not a priority now,” he says.

Irene Chekamoko, a service provider in Kapchorwa District, says in low income and rural families, family planning is a private affair, which women rarely share with their husbands.

“In our culture, there are many myths about family planning. However, some women had been empowered and were secretly visiting our clinic and other health centers. But now, everyone is at home. What excuse can a woman give to leave the home for two or more hours?”

She says this is causing friction, leading to gender-based violence (GBV). “Since the lockdown began, we have lost five men in four sub-counties, suspected to have been murdered by their wives. On average, our clinic used to get 25 clients every day, seeking information and contraceptive commodities. Now, we barely have ten.”

The lockdown has also put a barrier on the availability of SRH services. For instance, Reproductive Health Uganda (RHU), a non-governmental organisation that enables universal access to rights based SRHR information and services, has three clinics in Kampala, in the areas of Kamwokya, Bwaise, and St Balikuddembe market.

For the first two weeks of the lockdown, those clinics remained non-operational because, according to Dr Kenneth Buyinza, RHU’s clinical services manager, the organisation failed to get stickers that would enable them to transport their staff to clinics.

“Upcountry, the bureaucracy is easier to navigate because some of our members are on the district taskforces. But in Kampala, even the resident city commissioners of the divisions where our clinics are established refused to clear us.

So, people would come for services but find the doors closed,” he says. Two of the clinics only reopened this Monday.

Ban on transportation

According to Karamuzi, for the past three years, there have been stock outs of contraceptive commodities in government health facilities in Mbarara. The ban on transportation has escalated the situation.

“The main stock out is Depo-Provera (an injectable form of birth control). Also, method-mix is poor, which means women do not have options to choose from. If you were using pills and on your next appointment you find a stock out, you will be forced to take what is available,” he says.

In Gulu, things are not any different. Silda Anicia, a service provider, says although medical vehicles are moving within the district, they cannot transport contraceptive commodities to different hospitals because of the stock out.

“Some health centres have run out of short-term family planning methods, such as pills, male condoms, Depo-Provera, and Sayana Press. The little they had was consumed before the lockdown. Yesterday, some VHTs came to me, demanding for Sayana Press. But, I had nothing to give them,” she says.

Sayana Press is a new contraceptive injection on the Ugandan market which prevents pregnancy for three months. It has been lauded as an innovative injectable contraceptive because a woman can inject herself with it, as opposed to going to the health centre for an injection. With good distribution, Sayana Press can help millions of women prevent unwanted pregnancies. Dr Makanga, though, insists the country is not facing a shortage of Sayana Press.

“We have sufficient stocks in National Medical Stores, but it is a new product, and we have to train service providers on how to administer it. We have a strategy of expanding its use throughout the country after two years. The training process is ongoing. The only challenge has been the advent of coronavirus.”

Chekamoko says Kapchorwa District run out of pills and condoms at the start of the lockdown. “Women are being advised to buy pills from drug shops. However, people are not working; where will they get the money? We used to give out emergency contraceptive pills (morning-after pills) and condoms during our outreaches. Now, I fear that without emergency contraception, women are going to have unwanted pregnancies.”

The PMA 2020 survey found that 9.3 percent of unmarried but sexually active women were using emergency pills as a contraceptive method, up from 7.6 percent in 2017. Of course, the strain of unintended pregnancies has an immediate effect on household incomes.

Since the lockdown, the National Medical Stores has not been distributing contraceptive commodities. However, Dr Makanga says the ministry had recognised the critical need for such commodities in the country.

He says: “Early this week, we had a meeting and we are coming up with guidelines to ensure that NMS starts distribution. We are discussing innovative ways to ensure that the commodities reach households.”

Way foward

Short of including SRH services and family planning on the list of essential services, the way forward will be disastrous for the country’s economy and service provision.

“Government should set in place measures to allow us resume provision of SRH services through outreaches. These outreaches should, of course, follow the standard operating procedures for gatherings,” Karamuzi advises. Anicia says intergration is the way to go.

“In Gulu, the taskforce is exploring integrating family planning information with the COVID-19 information the VHTs are disbursing commodities to the communities. Unfortunately, VHTs can only distribute short-term methods.”

Since government health facilities are still operating, MoH should consider – when the contraceptive commodities are finally stocked – providing women with commodities to last them five or six months.

Population burden after the pandemic

At three per cent, Uganda population growth rate has always been high. However, now experts are predicting a rise in unwanted pregnancies and abortions – and a baby boom.

“If someone is not on a family planning method, and they are living in the same house with their husbands, what do you think will happen? A woman has to respect her husband and fulfill their conjugal duties,” Anicia says.

Dr Buyinza argues that there are already set precedents. “In my experience as a frontline health worker, I can tell you that nine months after the Christmas holiday, between September and October, there is a surge in deliveries at health centres. But now, you can imagine how big that will be with a five-week lockdown.”

Sexually active youth have not been spared either. MoH and donors came up with a strategy of establishing youth friendly corners at health facilities to increase the uptake of SRH services by young people but they are currently closed.