Prime

Kuka survived female circumcision and dedicates her life to protecting all Sabiny women

What you need to know:

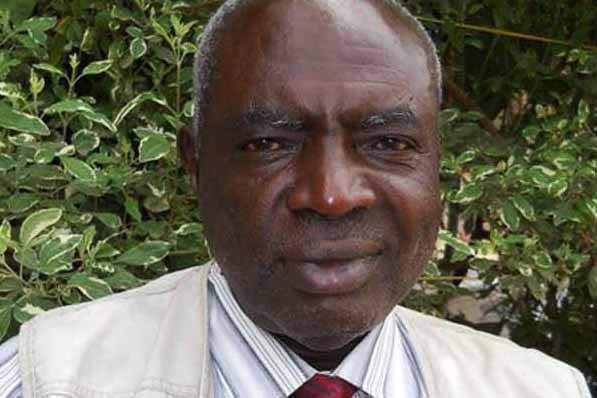

For her spirited fight against Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in Sebei sub-region, spanning more than 30 years, Jane Frances Kuka recently won an award from Action Aid and also scooped the Tumaini Lifetime Achievement Award as the Heroine of the FGM fight. Her story is one of a Sabiny woman who, as a child, stood against the knife to emerge a successful dare-devil as Ivan Okuda found out.

It all started with the ghastly sight of a fellow lass screaming her heart out with legs vulgarly spread apart as excited elderly women surrounded her. Armed and yearning to bring the formidable curved knife down to chop off that sensitive part of a woman and later jumping hysterically upon pouring yeast on the mutilated part.

Then followed her grandmother’s touching narration. At 50 years, she had since abstained from sex and subsquently moved out of her husband’s house. Reason? The old woman explained to her daughter-in-law that when you keep rubbing the circumcision scar, the wound re-occurs, making penetrative sex painful. Her price for circumcision had therefore become total abstinance.

These two episodes were to later turn around the life of a then shy Jane Frances Yasiwa, turning her into an anti-Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) activist many consider Sebei’s most phenomenal woman.

As we approach her humble office in Kapchorwa Town, Kuka gets up fast from her chair, welcoming each of us with a firm handshake, exuding warmness all round.

“I was born in Sipi, here in Kapchorwa. Mummy tells me I was born in the 1950s, but I feel 60 years old,” she says laughing, before adding, “We are six girls and none of us is circumcised but the three boys are circumcised.” There she goes, anxious to share that FGM story, the gist of this interview anyway.

The empowerment to resist

Kuka was lucky enough to be born in an enlightened family and that in itself was integral in the making of the activist. Her grandfather was a village chief but one who is “fairly progressive and objective like my father, though he was known for his toughness. People would at times burn our huts in revenge.” Her mother, Miriam Chelangat, was circumcised but always whispered to her first born daughter, “I want to be the last woman to be circumcised in this family. Make sure you don’t get circumcised because there is nothing good in it.”

Hers was a conservative, brutally protective mother. “She always told me to run away whenever boys came to disturb me and to tear to pieces any love letter. That helped me a lot because many of my peers got pregnant and circumcised,” Kuka shares with a deep Sabiny- accented, almost shrill voice.

At a boarding school in Gamutui Primary School, children were always taken to witness FGM in the neighbouring communities. For her, it was one sight that changed her life. “I had never seen a woman suffer like that with people jubilating as they cut her in front of us. I ran to my teacher who was a nun and like mummy, she told me I could only survive that experience by reading hard and becoming a teacher.”

Her ambition, however, was far away from the teaching profession. “I badly wanted to become a nurse or police officer because of their nice uniforms, but because of the fear for the knife, I accepted to become a teacher,” she shares with undisguised nostalgia.

That turnaround of ambition was to lead her to the Mbale-based Nyondo Teachers College in 1966, where she qualified as a teacher in 1969 returning to Gamutui Primary School as a music teacher.

The pressure, threats and my resistance

She later upgraded to a grade three teacher at Ggaba Teachers’ College. And the pressure from her father to be circumcised as required by her Sebei tradition began to mount. Each time he communicated, he pleaded with her to return to Kapchorwa and save him the humiliation, intimidation, and the cultural outcast-like treatment.

“I stood my ground and told him that if it is a party they wanted, they could circumcise my brothers. They then vowed that I would not get a man from Kapchorwa, to which I said fine, there were many men elsewhere,” she recounts, staring at a poster of a mean-looking policeman pointing at the words, “FGM is illegal, stop it.” She just couldn’t imagine herself, now an accomplished teacher being circumcised publicly, in full view of her pupils.

Getting hitched

On the subject of love, in 1972, a one Steven Kuka emerged and proposed. They had met when he still studying at Nyondo Sebei College, from where he had continued to send her letters. “He at first kept it secret that he was Sabiny too, thinking I would reject him for fear of being pressured to be circumcised,” she recounts. The name Kuka has since the age of 20 stuck, after the two got married. There was no wedding but traditional ceremony, which was boycotted by some people given that she was not circumcised.

The marriage came with an 11th commandment though. Steven had to promise to stand by his wife when the pressure to go traditional mounted. Her husband was fine with the condition, but not her mother-in-law who hurled insults at her son’s wife, castigating him for marrying a girl when there were women in Kapchorwa.

“At times my husband would subdue to the pressure and come back home drunk, asking how long it would take me to be cut. I would remind him of our agreement,” she recollects. Steven is a businessman and retired banker.

Pressure from work

In 1988, when Kuka was promoted to Principal of Kapchorwa Teachers’ College, she became the only woman to sit in the district council. Her first meeting in the council became what broke the silence that has since shaped the anti-FGM movement in Uganda and beyond.

“All the council members, who were men, spoke so bitterly about a growing movement of women de-campaigning female circumcision and their suggestion was to forcefully mutilate them, starting with me,” she narrates, adding, “I tried to tell them it was harmful, but they shouted me down.” She walked out, dashing to Kampala to meet Joyce Mpanga, then Minister for Gender to whom she shared her ordeal, compelling her to go to the undulating hills with two doctors, both Sabiny to educate the masses on the health dangers of the practice to the women. “The doctors spoke so well that by the end of their talk, the councilors were all asking why all along they had not been told about these risks. They relaxed the law from compulsory to optional and that boosted my campaign,” Kuka recounts.

Going for the public platform

She now sought for a bigger platform to amplify her voice. There was no other place than the August House though she lost as proponents of culture “de-campaigned me, saying I was going to end their culture.” That was 1989. The same was true for 1994 elections to the Constituent Assembly. She was down but hardly out.

Reaping the benefits

“In 1990, when I went to Ethiopia for a conference on female genital mutilation, I realised that the situation was even worse in other parts of Africa,” Kuka says. This grim reality was to inspire the birth of the Inter African Committee on Traditional Practices, focusing on other practices too like plucking children’s lower canine teeth, and gender-based violence and discrimination.

“Most Sabiny men restrict their women to the kitchen but I started to sensitise them, and we started to see women attend village meetings,” the mother of six says, a smile plastered on her face.

For the 60-year-old, life is about choices and sticking to our conviction. Her calling now is to spread this philosophy to the youth and that’s why when she is not in office, her leisure time is spent reading newspapers and listening to inspirational music. If not, she will be at a rally talking to the youth, supervising school anti-FGM clubs and preaching development on radio.

Factfile:

In 1996, Jane Francis Kuka became the woman Member of Parliament for Kapchorwa, and was appointed Minister of state for Gender and Culture. The following year, she recounts that no girl was circumcised in Kapchorwa. “It is in the records. I became bolder and more vibrant on FGM. In 1998, we invited the president to launch the culture day and he became our patron for the FGM movement.” Kuka was on fire, flying around the world, raising awareness and lobbying for support to the movement.

“We identified 30 girls, those who complained to us about the pressure to be circumcised, and hid them in Kampala, paid their fees and I’m happy they graduated and survived FGM,” she proudly recounts. In 1999, she was transferred to Ministry for Disaster Preparedness and Refugees. “400 women were cut in 2004, and the president returned me as the RDC Kapchorwa in 2007. I have tried to consolidate the gains but my reach is limited. I wish I had the capacity to reach out to Bukwo and Kween districts where women are now circumcised in caves and by the traditional birth attendants during labour,” she says.

Hand in hand with ActionAid

Kuka was recently awarded by ActionAid International for “creating a conducive environment, supporting and promoting ActionAid work in the Sebei region.” This joins the Life Time Achievement Tumaini Award she won in June.