Dr Kanyike reviews patients during a sickle cell clinic at Joint Clinical Research Centre recently. Photo | Beatrice Nakibuuka

Jane Nalwoga is a bright and ambitious 12-year-old resident of Nansana, a Kampala suburb. She loves school and dreams of becoming a doctor. But Nalwoga's life took a dramatic turn when she was diagnosed with sickle cell anaemia (SCA) at the age of five.

As she grew older, Nalwoga began experiencing frequent headaches, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating in school. Her parents thought it was just a normal part of growing up, but little did they know that the sickle cell anaemia was silently affecting her brain. One day, she suffered a severe stroke that left her unable to speak or move her left arm. She was rushed to the hospital, where doctors discovered that she had developed brain vasculopathy, a common complication of SCA.

Her dream of becoming a doctor was shattered, especially since she is unable to attend school.

Moses Kyazze, on the other hand, was diagnosed with sickle cell disease at the age of eight months in 2009. In the early years of his life, he was able to attend school but he would often fall sick. One day while sleeping, he suffered a stroke. By the time he was taken to Mulago National Referral Hospital, doctors said the stroke had affected his ability to sit or talk.

Despite the challenges, Kyazze's mother remains hopeful and has relentlessly taken care of him for the past 15 years. With support from a few friends, she was able to acquire a wheelchair for her son and has learnt to manage his condition.

Kyazze now receives hydroxyurea therapy and once in a while goes for apheresis to help reduce the risk of the stroke. Apheresis is a process in which a machine removes blood stem cells or other parts of the blood from a person's bloodstream and then returns the rest to the body.

Kyazze and Nalwoga’s stories are not unique. In Uganda, thousands of children with SCA are at risk of developing brain injuries and neurocognitive dysfunction. The condition affects one in 20 children born in Uganda, making it a significant public health concern.

Occurrence

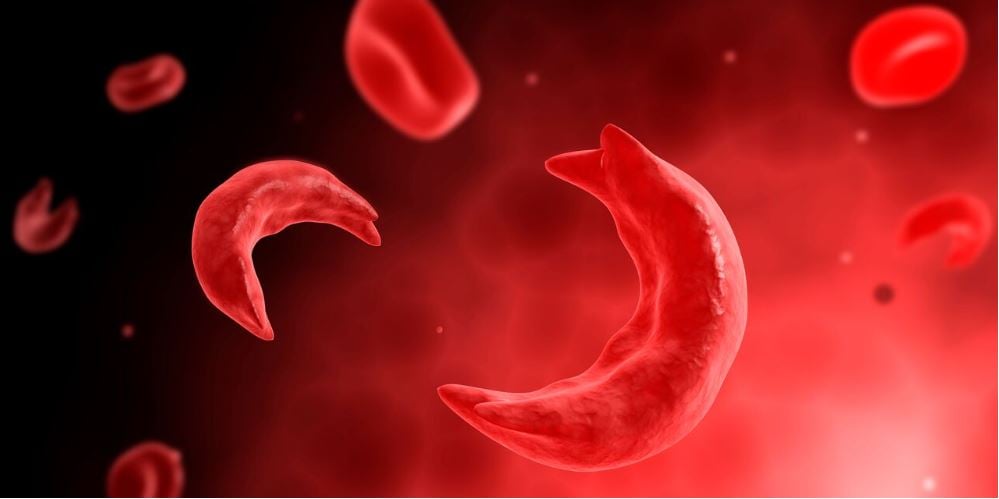

Sickle cell anaemia is one of the most commonly inherited blood disorders worldwide, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. Approximately 225,000 children with SCA are born in Africa each year.

In Uganda, one in seven people carry the abnormal sickle cell gene and 15,000 to 20,000 children are born with SCA annually. SCA patients usually suffer from episodes of excruciating pain, anaemia (reduced blood levels), yellow discolouration of the eyes and body, and infections.

According to the centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a stroke can happen if sickled cells get stuck in a blood vessel and block blood flow to the brain, making it harder for the brain to get the oxygen it needs to function properly.

About 10 percent of children with SCD will have an asymptomatic stroke, which is sometimes fatal. Increasingly, many of the survivors will develop brain injuries, especially stroke.

Prof Richard Idro, a researcher at Makerere University College of Health Sciences, says there is a high burden of neurological and neurocognitive disorders among children with sickle cell disease from a recent study conducted at the sickle cell anaemia clinic at Mulago National Referral Hospital.

What causes the injuries?

Sickle-shaped red blood cells can damage blood vessels, leading to narrowing, blockage, or rupture, which can cause a stroke. Also, SCD increases the risk of blood clots, which can block blood flow to the brain, leading to a stroke.

Sickle cells can stick to blood vessel walls, causing blood flow to slow or stop, leading to a stroke. The disease can cause vasculopathy, a condition where blood vessels become damaged and narrowed, increasing the risk of stroke.

Dr Francis Kyazze, a consultant in sickle cell treatment at Joint Clinical Research Centre (JCRC), remarks that early detection and management are critical to preventing stroke and other complications.

Complications

People with sickle cell disease (SCD) are at risk for various neurological injuries such as stroke, silent stroke, damage to blood vessels in the brain leading to damaged brain tissue, and narrowing of the blood vessels in the brain leading to stroke or transient ischemic attacks.

“They may also experience difficulty with attention, memory, executive function, and processing speed, nerve damage, often causing pain, numbness, or weakness in hands and feet, damage to the spinal cord due to inadequate blood supply,” he says.

Seizures can happen due to brain damage, infection of the protective membranes around the brain and spinal cord, fluid buildup in the brain as well as bleeding between the brain and its protective membranes.

Why do the injuries happen?

Brain injuries in people with sickle cell anaemia can occur due to various mechanisms. Dr Kanyike says the sickle-shaped red blood cells block small blood vessels, reducing blood flow to brain tissue.

“Sometimes, blood clots form in blood vessels, blocking blood flow to brain tissue. Chronic inflammation damages blood vessels and brain tissue and low red blood cell count reduces oxygen delivery to brain tissue,” he says.

Damage to blood vessel linings disrupts normal blood flow and promotes clotting, thickened blood slows down blood flow, reducing oxygen delivery to brain tissue but some individuals with SCA may be more susceptible to brain injuries due to genetic factors.

Interventions

Regular monitoring, preventive measures, and prompt treatment remain crucial for the prevention of stroke among people with sickle cell disease. Most importantly, haemoglobin levels should be above eight.

Dr Kanyike remarks that the transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) is a diagnostic test used to measure blood flow to and within the brain. This can help tell if a person with sickle cell is at risk of stroke or not.

Treatments such as hydroxyurea therapy, Dr Kanyike says, reduce sickling, improve blood flow, and lower stroke risk.

Regular transfusions can reduce stroke risk by increasing oxygen delivery and reducing sickling. Also, those who can afford red-blood-cell exchange (apheresis) should go for it since this improves the quality of life of a person with sickle cell disease and reduces the risk of stroke.

Stem cell transplant, although not yet vailable in Uganda, is a potentially curative treatment that replaces the bone marrow with healthy cells.

Nalwoga and Kyazze’s stories highlight the need for increased awareness, screening and support for children with SCA in Uganda. With proper management and care, these children can lead fulfilling lives and achieve their dreams.

Signs and symptoms

For injuries such as silent stroke, there may be no noticeable symptoms but someone may experience cognitive impairment, memory loss, attention deficits and processing speed difficulties.

“Sometimes, one may experience sudden weakness or numbness in the face, arm, or leg, failure to close the mouth, sudden confusion or trouble speaking, trouble seeing in one or both eyes, severe headache, difficulty walking, dizziness, or loss of balance, nausea or vomiting, and coma,” Dr Kanyike says.

If you or someone with SCA experiences any of these signs and symptoms, seek medical attention immediately. Prompt treatment can help prevent further brain damage and improve outcomes.