Prime

IVF: Hope of conception for childless couples

A laboratory technician working with follicular fluid at the stage of introducing sperm to the ova extracted from a woman’s body. Photo by Rachel Mabala.

Children are a joy to have; and the yearning to be a mother is something few women can escape.

By 2002, Amina Musoke* had lived through the joy of bringing four children into the world. Her oldest, a boy, was eight years old, and the youngest was two. Living on the outskirts of Kampala, theirs was a low-income, but happy family, until tragedy struck.

“I was at work. There was a boy, much older than my children, who lived with us and took care of them. Like many young men, whenever there was a fault with the electricity supply he would try to repair it. On that day it rained heavily and the electric wire fell off the pole.

When the rain reduced to a drizzle, the children went out to play. One of them, I never got to know which one, stepped on the wire and was electrocuted. The second child came to pull him away and was also electrocuted. The other two died trying to help their siblings,” recalls Musoke.

In one day, in the space of a few seconds, Musoke lost all her children. Two years earlier, after the birth of her youngest child, she and her husband had decided that four children were enough.

Musoke underwent tubal ligation surgery.

More commonly referred to as “having the tubes tied”, tubal ligation is a surgical procedure in which a woman’s fallopian tubes are tied, blocked or cut to prevent eggs from reaching the uterus for implantation. It is considered a permanent method of birth control.

A ray of hope

While Musoke was grieving for her children, her husband got another wife and started a new family.

“After three years, in 2005, I started wondering if it was possible to have a child again. I wanted to find out if the doctor who had “tied my tubes” at Mulago hospital could rejoin them so that I could conceive.”

At 29, the doctor said, Musoke was still young enough to conceive without difficulty but since tubal ligation is permanent, he could not help her.

“He gave me Dr Tamale Ssali’s number, saying he might have a solution for my problem. I wanted a child and when the doctor explained that it was possible, I believed him. But it was a very emotional time for me because I had no one to share my hope with. I could not tell my husband.”

It took Musoke two years to get the courage to seek IVF treatment and by then, she had saved Shs150,000.

In 2007, she went to the Women’s Hospital International and Fertility Centre in Bukoto, Kampala.

The registration fee for the IVF treatment took Shs50,000 out of her savings.

“A doctor explained the procedure of getting pregnant through IVF but said it would cost Shs2.5m.

I wanted to cry because it was the kind of money I had only heard about. I had never had it, and there was no hope of getting it. My husband was not even aware where I had gone that morning.”

Returning home, dejected, Musoke went to sleep convinced that a baby was out of her reach. Then at 7am the next morning, she was awoken by a message on her mobile phone.

“Dr Ssali sent me a message to come to the hospital. While reviewing my file, he had been touched by my experiences. That morning, I opened up to my husband about my plans. He did not agree with having children that way but he accompanied me to the hospital.”

At the hospital, they required proof of the tragic accident in which Musoke lost her children. Thus, Musoke had to bring a letter from her Local Council (LC) chairman, the police and witnesses.

“Dr Ssali offered me a free treatment procedure. However, when my husband was called to produce his sperm, he almost refused.

He thought the doctors were using the treatment as a cover to fornicate with their patients. But when he entered the room he finally believed that it was genuine.”

A child at last

Although some women require more than five IVF procedures to conceive, Musoke conceived in November 2007, immediately after the first procedure. In August 2008, at 32 years, she gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

“We were so happy,” she says with tears in her eyes. “Having a baby after the pain of losing my first four children was a miracle from God. The child resembles my husband so much that whatever doubt was in his mind disappeared.”

However, in spite of the joy, Musoke has learnt the hard way that not all people will accept her child. Some of her neighbours and relatives taunt her about the “baby from an injection”.

“I do not want to reveal the identity of my child because it may cause her problems in the future.”

Trying for another child

When I met Musoke at the hospital, she was starting a new treatment schedule. “If my other children had lived, they would be young men now. When my daughter was three years old, I had another IVF procedure and I got pregnant. Unfortunately, the child died in my womb. I want to have another child. Please pray for me to succeed this time,” she asks.

It takes money to have a child, so Musoke and her husband are saving whatever they can to complete the treatment and procedure.

“I want to encourage childless women that it is possible to get pregnant. During my counselling sessions, I learnt that barrenness is not a death sentence. If the treatment is expensive, you can work out a plan with the doctors.”

Carrying out fertilisation outside a woman’s womb

A series of tests provide a basis for the diagnosis and the decision on the treatment. If the uterus cannot carry the pregnancy to term, then the only option is surrogacy.

If the couple is placed on IVF, according to the diagnosis, a treatment programme lasts 40 days.

“The first step is to down-regulate the body. In the first 21 days, we administer a contraceptive, microgynon, to make the reproductive system match our treatment programme.

If you usually get your periods on the 15th, and the treatment programme indicates that you must start on the 20th, then your system will be brought down to zero.”

Spontaneous ovulation, where the hormones produce ova and prepare the uterus, is stopped.

“For about 10 to 12 days, we stimulate the ovaries to determine if the ova are due for release. We use a trigger injection to induce ovulation.”

Retrieving the eggs

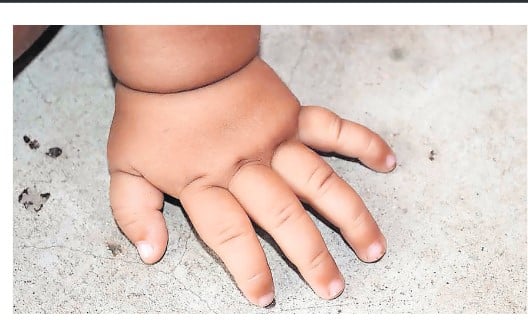

“Depending on how fast the patient responds to stimulation, the eggs are collected on the 12th or 14th day using a puncture needle and sanction pump. The needle punctures the vaginal walls to collect the follicular fluid, which contains the eggs,” Eluga explains.

The procedure is done under general anaesthesia and up to 30 eggs can be retrieved. The fluid is placed in a lab dish for the embryologist to identify the eggs under a microscope.

Fertilisation

“The identified eggs are washed and put in an incubator where they stay warm until a decision is made based on the man’s sperm.”

If the semen is normal, through sperm washing, it is stripped of inactive cells. A routine mix is done in a lab dish with a ratio of 1:75,000 – with one egg mixed with 75,000 sperms.

Where the sperms are inactive, the embryologist injects a single sperm directly into the egg using an intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection. Afterwards, the ovum is returned to the incubator.

After 24 hours, the embryologist checks the egg to ensure that it has formed a zygote and has started dividing.

“If the progress is good, a decision is made whether to transfer the embryo back into the uterus or into the incubator. Embryo transfer should be done on the second, third, fifth and sixth days.”

After two weeks, the patient will return for a pregnancy test. The other eggs that were extracted from the follicles are kept in a freezer until the woman needs them.

Reasons behind the choice to have In Vitro Fertilisation

While In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) takes place outside the womb, Morris Eluga, an embryologist at the Women’s Hospital International and Fertility Centre dismisses the myth that only middle-aged women seek IVF treatments.

Who gets IVF treatment?

“Women as young as 18 come in for treatments. A woman who has suffered premature menopause is a candidate for IVF because the condition causes the ovaries to lose their primary function.

Sexually transmitted diseases, if left untreated, block the fallopian tubes, in some women, recurrent miscarriages prevent them from carrying a pregnancy to term.”

For some women, career comes before anything else and since the biological clock closes down at 45, they may decide to freeze their eggs until they are ready to have children.

Dead sperms

“Some men do not ejaculate or they may have erectile dysfunction. Others are sub-fertile, where they have low sperm count or dead sperms,” says Eluga.

In our culture, when a woman does not conceive, the blame falls on her, ignoring the fact that the husband could be the problem.

“During this time, the woman is probably using traditional herbs to remedy an otherwise well-functioning uterus. These herbs are dangerous to her health. When sperms are dead, they cannot fertilise the ova.

On the other hand, some sperms may be alive but do not have the energy to move. We sort them out through a hypo-osmotic swelling test on the semen. The sperms which swell are active.”

Even if 99 per cent of the sperms in a given sample of semen are dead, IVF can proceed with the one live sperm.

Chances of getting pregnant

“The chances of getting pregnant depend on the patients’ condition and the duration she has lived with it. A woman who has had a condition for 15 years does not have the same chances as a woman who has discovered hers at 25.”

Eluga says although they hope that a woman will get pregnant on the first trial, the longest a patient has taken is four years, during which nine trials were carried out.

Checking for genetic defects

As a part of IVF, genetic studies are carried out on embryos.

Dr Gilbert Ahimbisibwe, senior medical officer at the Women’s Hospital International and Fertility Centre, says that the process of Pre-Genetic diagnosis (PGD), determines the quality of the genes. PGD is also used when the parents want to predeterminetheir baby’s sex.

“On the second day after fertilisation, we do a study on one cell. At this point, they are still non-specialised cells or stem cells and the removal of one has no effect on the embryo,” explains Eluga.

PGD enables the embryologist to detect genetic illnesses before the embryo is transferred into the uterus. Such illnesses include sickle cells, haemophilia, and chromosomal abnormalities such as Down’s Syndrome.

If a genetic illness is detected, we cannot use the embryo for IVF. It is discarded and another one is tested, since more than twenty eggs are taken out of the woman. If all the eggs show signs of genetic illnesses, the couple is advised to opt for surrogacy, where the eggs of another woman are used.

definition of terms

In vitro fertilisation: This is a process of manually fertilising the egg by combining it with the sperm in a laboratory dish. The fertilised egg is then transferred to the uterus.

Sperm washing: This is the process of separating individual sperms from the seminal fluid. It involves removing any mucus and immobile sperm to increase the chances of fertilisation and remove disease-carrying material in semen.

Pre-genetic diagnosis: Refers to the process of screening the embryo for specific genetic diseases (while it is still in the laboratory dish) before it is implanted into the uterus.

It involves checking the genes and chromosomes of the embryos to prevent families from passing on genetic diseases to their children

Premature menopause: Refers to the loss of the normal function of the ovaries before the age of 40. A woman with the condition will stop having her periods and cannot get pregnant.

Erectile dysfunction. Occurs when a man is unable to get and or maintain an erection. He cannot have sexual intercourse, and thus cannot father a child biologically.

Intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection: It is an IVF procedure in which a single sperm is injected directly into an egg, to ensure fertilisation

Down regulate:. This is a process of introducing an external variable (chemical) to make body cells less sensitive to natural hormones produced by the body

Follicular fluid: This is the liquid which surrounds the ovum in the ovary.

Zygote: This is the first stage of life and starts after the egg and sperm have been joined.

Embryo: The collection of cells that has developed from the fertilised egg before the major organs have developed.

Information from the Women’s Hospital International & Fertility Centre, Ntinda, Bukoto, Kampala.

*Names have been altered to protect identity of source