Prime

School for the deaf: Managing amidst challenges

From top to bottom: Pupils during one of the meal times at the shool, a teacher teaches the alphabet using sign languages, the headboy communicates to pupils in one of the classes. PHOTOS BY ISMAIL KEZAALA

What you need to know:

Between having limited space, more than the required teacher-to-pupil ratio and relying on grants and donations, one shool endeavours to provide an education to deaf children, Christine Wanjiru Wanjala writes.

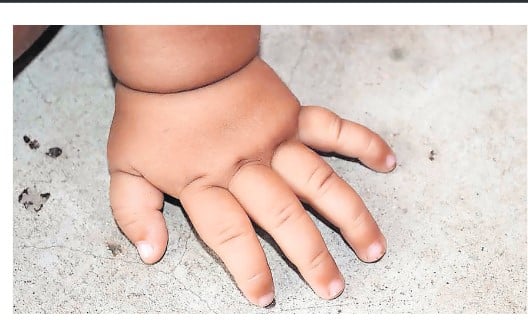

Anyone who has gone through the hustle of getting a suitable school for a child knows it’s no walk in the park. Yet all that trouble is nothing compared to what a parent with a deaf child or deaf children have to go through. You can count the number of institutions catering for such children in the whole country on the fingers of one hand, not to mention those that are around the city.

At the Ntinda School of the Deaf, one appreciates the true value of hearing. Not to make fun of their disability, but the school is like a headmasters dream. Silence everywhere except for the occasional honking of cars on the nearby road. Even the corridors are quiet, no shouting teachers, or children chanting vowels.

The preschool section is quiet, except for one father who is patiently pushing his child around and around on the merry go round. The sun is hot but this doesn’t seem to faze the sweating father, he continues playing with his quiet unresponsive child.

“He is a new student,” the acting deputy headmaster, Mr Daniel Othieno, explains of the child. “His father is here to help him adjust. Unlike other children, deaf children find difficulty expressing themselves especially in an unfamiliar environment.”

I am was there to find out about the new pre-school section but Mr Othieno corrects me, “It is not new as such, we have had a preschool session running from 8:30am to 12:30pm every Wednesday where the children would come accompanied by their parents.” This was the only form of pre-schooling the children would get before going for primary one (P. 1) until Sign Health Uganda and Sign Health London proposed to help the school expand. This birthed the pre-school section complete with a trained teacher and a daily schedule.

An empty pre-school

The section was officially launched on April 14, 2011, but didn’t really begin functioning since schools were almost closing for first-term holidays.

On June 1 ,the beginning of the new school term saw the preschool open again to just a few students.Despite the slow start,the opening is a great step for the school which hasn’t had a daily pre-school program since its founding in 1959. “With deaf children parents do not take the risk of sending boda bodas to drop them and pick them from school,” he says, “The parents,well aware of their children’s communication challenges,are cautious of the situations they expose them to”.

The brightly coloured classroom has twenty or so little chairs, but even on Wednesday when there is the highest turn up, they are barely filled. On the walls are the letters of the alphabet both in the normal version and in sign language. I take some minutes to try to cram at least three while I wait for the teacher.

The smiling lady looks like the kindergarten teacher your child will talk about all day. Her easy disposition and ready smile must work wonders with children. She tells me she is a trained teacher and also did a specialised course on teaching deaf pre-schoolers. I can’t help but wonder if she has faced any challenges so far. “I am pretty new at the job and so far so good,” says the teacher.

Too small to meet the need

I want to know if the primary school section has enough children. I have seen one or two coming to the office, which makes me all the more curious. In my ignorance I wonder quietly, how many deaf children can there be?

It is therefore a surprise when Othieno tells me one of the challenges Ntinda School of the Deaf faces is limited space. “Now more than ever people are aware disability is not inability. They do not hide deaf children anymore so we have a lot of people wanting to join us. Parents also spread the word to other parents and we end up getting children from as far as Congo, Rwanda, and even Sudan”.

The number of students the school takes in each year for primary one depends on the number of available spots left by those who sit the PLE exams. One has to apply a year in advance to get a spot in their November intake. Othieno calls the selection period the worst in the year. “Having to turn away children you know really need and want to be in the school is really hard.

Sometimes we have to tell the parents to go home and wait another year.” he says with eyes downcast. They always refer such parents to what Othieno calls other stakeholders; Mulago School for the Deaf and Kampala School for the Deaf in Gayaza.

The school with its 200-strong student population is already stretched as far as its facilities can go. It is therefore easy to understand his dilemma when faced with over 80 applications when he only has 12 available spots. The children who sit for primary seven exams have about four secondary schools to choose from. Ngora High School in Kumi, which has a section catering for deaf children, Wakiso Secondary School, which also has specialised facilities for the deaf, Mbale Secondary School For The Deaf and Nancy School For The Deaf.

Special education needs and challenges

During the lunch break I see the children milling about the compound in groups silently conversing in sign language. There is a grunt here and there, the closest they come to is a shout. It suddenly hits me, without their hearing, they use their eyes to communicate and thus need light even in the night.

Othieno estimates the electricity bill at about Shs2m each month. A figure he says strains the schools already stretched budget. Like in any schools they have indiscipline cases, but thanks to the strict rules that is not a problem. The students themselves are very vigilant. Because they can’t hear, they use their eyes very well, and are quick to tell on each other.

Unlike regular schools however, handling deaf children requires special care and patience. “You need to be able to wait to see results and develop love for the children. What we do here is more than teaching.” The deputy headmaster who has taught deaf children for 15 years says they double as counsellors and caregivers both for the parents and the children. Many children go through trauma for the disability and the parents also need support in coping with the challenge of raising a deaf child.

All the children are boarders save for one or two whose parents opted for them to commute. The government pays for the teachers who are a mix of deaf and hearing teachers. Through a subvention grant from government they are able to get books, and other equipment required for the daily running for the school.

But there is still a great need for financial assistance. On paper all the children are supposed to pay for their up keep. The reality is very few actually do, mainly because their parents cannot afford it. “Many of our children are brought here by single mothers or grandmothers who have little means. Sometimes the parents bring them up to Ntinda shopping centre and then tell them to come to school.” Othieno blames the fathers taking off when they discover the child is deaf.

How do they bridge the gap then with so many poor children and so little funds? I ask. Thankfully they get donations from the well wishers every now and then. Also for some years now, Christoffel Blinden Mission (CBM), a German Christian organisation has been supporting the school for some time.

With just 17 teachers, the school policy of one teacher for every 10 students is heavily compromised. Many of the children also suffer from low vision and there is even a wing for the deaf and blind currently housing six children. The vision problems coupled with the various levels of deafness slow down these children a great deal. “They require more time with the teachers and more attention,” explains Othieno.

What strikes me is how there is no sadness here. You wouldn’t know there were all these problems by just walking around the school which boasts a carpentry workshop, a bakery and very clean dormitories. The children in their own way are happy, jostling, jumping around. One makes funny faces at me and I hear the clear ring of laughter from a group of girls.

“They do have their challenges, but they live their life and compensate in other things.” says the soft spoken deputy. The empty playground is proof enough; there is no grass except a few tufts at the edges. Clearly, when it comes to play their deafness is not a factor.