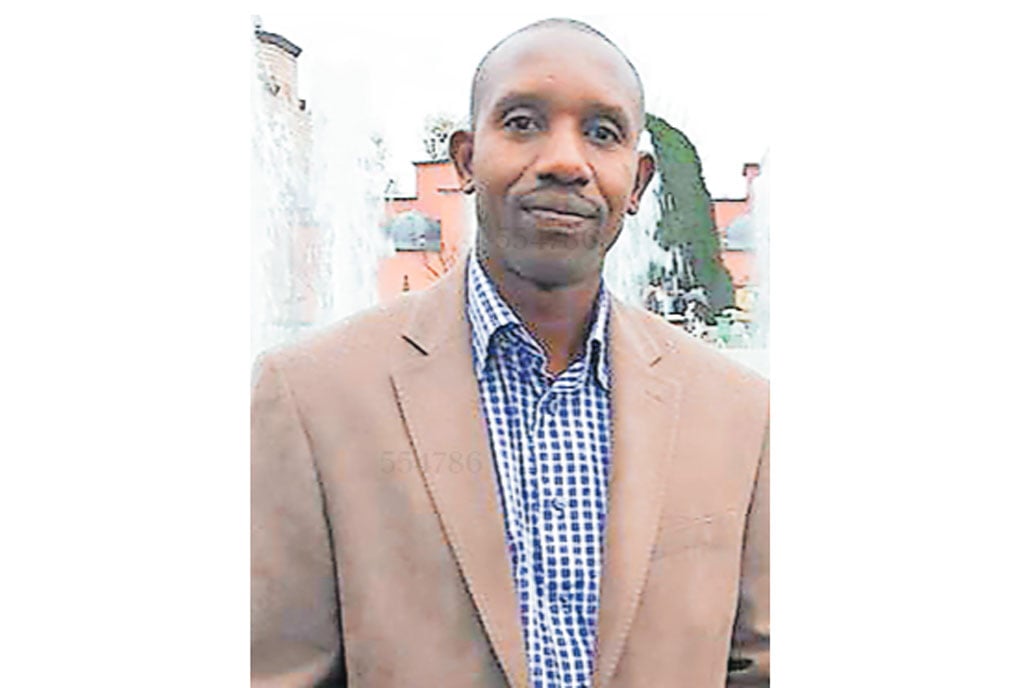

Julius Adomati suffered domestic violence.

At 30 years, Julius Adomati, a resident of Ombamba Village in Ajia Sub-county, has had to raise his three children single-handedly after his wife (name withheld) ended their five-year marriage.

Adomati, a cobbler, who walks on crutches because he is physically impaired earns only Shs8,000 weekly as he struggles to afford basic welfare for his children.

"We have two boys and one girl, and I can only afford to pay fees for the eldest child because most of our family resources have been depleted in paying off loans."

Loan burden

For the past seven months lived as a single parent, Adomati has struggled to write off the Shs1.2 million debt slapped on him by his ex-wife before the breakup.

"This woman (his wife) secretly borrowed Shs1.2million for no clear reasons and without my knowledge,” the cobbler laments adding: “I had to sell all the produce to service the loan since the village groups wanted to take all my animals.”

The marriage, cemented through dowry that Adomati paid in 2019, ended early this year after his wife thought he was not man enough to fend for the family.

"Whenever I left for work in Ajia Market, she would dress smartly and leave the children home unattended to only to return at 10pm," he narrates.

An attempt to salvage the marriage

The best-known immediate remedies he sought never yielded, but only escalated the problem.

"Whenever I tried to talk to her about her late movements, she would get angry so I called for a clan meeting, but she did not heed any warnings," he recounts.

The disrespect continued to the point when she would deny him conjugal rights. He only got to learn about her infidelity after she abandoned him and the children for a wealthier man.

He says:"I was stressed but I kept the pain to myself because of cultural constructs and I feared to speak out."

His case is not isolated as more men like him in Arua and the vicinities have to suffer in silence from intimate partner violence because of such cultural beliefs on how family conflicts ought to be handled.

According to the Child and Family Protection Unit at Arua Central Police Station, about 67 male-reported cases of gender-based violence (GBV) were recorded from January to August 2024.

The findings establish different forms of abuse among the males with about 30 men experiencing sexual abuse, 12 men experience emotional abuse while 15 men experience economic abuse in a period of six months.

What is Aruba?

The silence of shame for most male survivors is associated to cultural connotations that limit the males from speaking out on the growing vice in the region.

Aruba is a Lugbara cultural justice mechanism intended to reconcile persons who have accessed the formal justice systems and escalated their conflict. The concept is evolved under the taboo, “Mundu ba ere ere” meaning the formal justice system breaks people and vital social relationships.

“In our culture, if a man and woman fight and it causes bruises and disabilities in the body you do not report it to authorities because it brings curses, death and strange illnesses in families. So, people are suffering quietly due to such cultural norms,” Susan Ezatia, a leader at Lugbara Cultural Institution-Lugbara Kari explains.

Aruba which was intended to help persons inflicted with various forms of pain in marriage to instead seek counsel from elders or handle matters within their households has been greatly misused as a punishment, especially for those experiencing abuse in their homes.

This misinterpretation of the mechanism that Aruba seeks to address in households explains the travails that Adomati is for a time confronted with.

“I could sue this woman, but I fear for my children's future to suffer misfortunes. Thus, I cannot continue with the matter to the police,” he shares.

Ezatia described Aruba as a mechanic to help families experiencing different forms of violence reconcile their misunderstandings. She notes that they even went to hospitals to examine this norm because it is said that one’s skin would become light or one’s children would die or get malnourished.

“Together with the victims, we examined children and discovered that the children were suffering from kwashiorkor,” she says.

She adds that many have come to the revelation that the negative connotations around Aruba are only a myth and system of controlling and torturing others.

“We have also had community dialogue where we engage the men and women and find out the causes of some of the issues. And, how they can be solved by including go-between or close family members to foster reconciliation hence changes in the community.”

Similar problem or breaking barriers

Lawrence Auma is testament to breaking the barriers caused by aruba. Auma shares his ordeal of surviving an 11-year abusive relationship.

“My Wife was only 17 and I was 22 years old when we got married. She was insecure with my work. Since I was a boda boda rider, she perceived every female client as my lover. This led her to becoming harsh towards me,” the 32-year-old survivor speaks out on the cruelty he faced while struggling to pull his family out of the grips of poverty.

“It has been tough, my wife would hear rumours about me and my female customers because she was idle as a housewife and would confront me at work and at home,” he says.

He recounts times he was embarrassed at work, and even days he had to go hungry because he was denied meals at home.

However, he decided to speak out and once the issue was not resolved at the family level, he approached the local leadership.

“When I involved the LCs, I was counselled and also kept in good company of other men with great solutions. I was also connected to a community organisation which offered my wife a role as a para-social worker. She is now busy and has no time to start conflicts.”

Ray of hope

Harriet Fikira, community-based advocacy focal person at Community Empowerment for Rural Development (CEFORD) expresses her concern about men’s silence which escalates GBV cases in Arua.

“Men tend to keep quiet because people believe they are strong and expected to tolerate their issues and if they speak, they are considered to be weak. This is different from the women who seek guidance and counselling,” she says.

Fikira recommends that men be availed safe spaces as a separate arrangement away from women to be able to speak openly about their issues.

“Men require a friendly approach and to be engaged more to talk about GBV-related issues and given private sessions where they can easily open up,” she emphasises further pointing out the cultural issues that limit male engagement.

“The males are afraid to speak out because once these issues are forwarded to authorities, they will require them to sacrifice animals for conflict resolution. So, the men rather suffer in silence,” Fikira adds.

To put an end to such hindrances, she mentions, “There is hope that this issue will end because cultural leaders are involved in our sensitisation meetings to encourage men to speak out on these issues.

“We are also meeting with men in communities since we realised that they are usually in groups which makes it easy to access them.”

The West Nile regional gender focal person at Arua Central Police Station, Jimmy Anguyo, says the authorities are working tirelessly to break the cultural barriers limiting men from seeking help.

“The cases reported so far have doubled those of last year, we are happy that men are coming out to report cases because violence is a crime. Police is working with Lugbara Kari, church leaders and other stakeholders to do sensitization to encourage men to report cases,” says Anguyo.

Most of the survivors, he notes, do not want to open up publically explaining, “Men believe that if they report a case of violence, they are no longer in charge of the home and the women have taken over their place. However, we are calling upon the public to report more cases of males violated by women for purposes of accountability, planning and management.”

Interventions

The authorities say the perpetrators are usually women avenging themselves on their husbands because they did not provide for the home and take advantage of their alcoholism when they are weak and unable to fight back.

The reported cases include malicious damage and threatening violence.

“Prosecution is not our priority, we prefer to settle matters outside court systems, especially those on family misunderstandings. So, we mediate, dialogue, conference and come up with a solution and if nothing is achieved, we use the court as last resort,” SP Anguyo explains adding: “We also do check follow-ups in their homes and if they are not progressing well, we advise accordingly.”

More interventions have been put in place by civil society organisations. For example, Save the Children has resettlement centres or shelters for children and families seeking protection from different forms of violence where the survivors are temporarily accommodated before they are linked to probation officers to locate their homes and help them return sanity in their families.

Ronald Kabagambe, a parasocial worker and resident of Etoleni Village, Kuluva Parish in Arua District, shares that the GBV-related cases against the males in the region are largely associated with poverty.

“Poverty pushes families into quarrels and wrangles which leads to GBV. The best way to address this, is through sensitisation in families and communities and involving local leaders, opinion leaders, religious leaders among others,” says Kabagambe.

Kabagambe urges men to know their rights and come out of suppression.

“There is need to step away from stereotyping men as the superior persons that ought to sit on issues because it affects their willingness to share challenges. He sums it up saying: “A dignity protected is a life lost to Gender-based Violence.