Prime

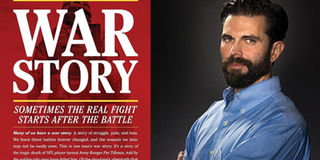

War Story: An unlikely mental health guidebook

What you need to know:

It is important that we give mental health as much attention as we give to our physical health

As the year begins, many of us will be casually referring to January blues or school fees stress. There is something very wrong with a society that has normalised sadness and stress. The fact is, if we let these everyday stresses become part of our lives, they rewire the way our brains function and how they react to situations. Once the brain has been rewired, it gets difficult to reset it again as Steven Elliott recounts in his book War Story. The book is a chronicle of Elliott’s struggle with mental illness and his dedicated efforts to find healing.

The story unfolds with Elliott, who in 2001 after completing his graduate studies at university, decides to join the army. Following the tragic events of 9/11, the United States of America declared war on the Taliban government in Afghanistan over their refusal to hand over Osama Bin Laden, the major suspect. Elliott joins the most elite section of the army known as the Rangers. The Rangers receive the most specialised training, which puts them at the frontline in every battle.

Although the training is vicious, Elliott manages to emerge as the best and graduates top of his class. Soon, he is deployed but his luck runs out because on the first day of his deployment, his company falls into an ambush, which results in three fatalities. One of the deceased is fellow officer, Pat Tillman who had been a famous footballer before enlisting. This would have been a normal thing because war is not a tea party, except for one small problem.

When the bodies were examined, it is discovered that the bullets that killed the officers belonged to the US army rather than the enemy. To Elliott’s platoon’s shock, it is believed that they could have been responsible for the shootings owing to the terrain they were in and the fact that it was at night. From that moment, everything changes for Elliott. Elliott and fellow officers become subjects of various investigations, which although ultimately exonerate them, inflict emotional and psychological damage.

Over the next several years as he tries to start a new life, Elliott finds himself resorting to alcoholism, pornography and cigarettes as coping mechanisms. When he is diagnosed with Post Traumatic Syndrome Disorder (PTSD), he tries counselling, exercising, medication but nothing works. He endures terrible insomnia followed by debilitating nightmares. When these mental problems later affect his marriage, he contemplates suicide. As he holds the gun to his head, he realises that killing himself will not solve the problem but he will be passing it on to his young children and wife and that will always be their legacy as result of being part of his life. He observes that to kill a man is to kill one man but to oneself is to kill an entire world.

This incident marks a turning point in his life and over the next several months, he not only seeks help but accepts it, especially from those willing to give it to him. He also decides to volunteer as counsellor for other veterans because having fallen to lowest levels of failure, he feels duty bound to help those who have failed or fallen.

Through his work with the veterans he discovers that every year, 7,300 veterans commit suicide due to untreated mental illness and many more languish, unable to reintegrate into the community after their tours of duty. Yet, there are no serious interventions being put in place to alleviate the problem. What is most striking about Elliott’s journey is the refusal to give up and give in to his circumstances.

In our society, it is normal for patients with physical illness to go from one doctor to another or try different treatment options. But when it comes to mental illness, we are quick to give up or settle for what is available even if it is not working for us. Our bodies react to different treatments differently. It is, therefore, painful to realise that mentally ill patients are expected to respond similarly to the same treatment.

Elliott experienced this approach but was invested enough in his healing to not just settle for what the experts prescribed. His search for healing led him to discover a trauma treatment technique called Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR). He had discovered that his illness was caused by a brain function malfunction that was sending wrong messages to his entire body causing adrenaline and cortisol to be dumped in his bloodstream. The EMDR helped rewire the way the body interprets messages, thereby controlling his body’s reactions to events.

Trauma and mental illness are obviously not confined to those who have been to war. And wars look different to each of us and can leave us as traumatised as those on the frontlines. It is important that we begin to give mental health as much attention as we give to our physical health. A society whose members are living with mental illness is unable to realise its full potential. When individuals struggle, their community suffers too.

Research shows that mental illness is on the increase and 14 million Ugandans are said to be battling the disease. Yet with the increased problem, nothing much is being done by way of infrastructure or sensitisation. We are reminded that we are the way and the wayfarers. And when one of you falls down he falls for those behind him, a caution against the stumbling stone. And he falls for those ahead of him, who thought faster and surer of foot, yet removed not the stumbling stone.

We cannot sit back and wait for government to intervene on our behalf; this is a war that will require concerted effort. Start by taking care of your own mental health, if you are unwell, reach out for help. Once you are in charge of your own health, you will be able to help those in need and helping eliminate stigma about the illness.