Prime

61 years of independence: Who are we?

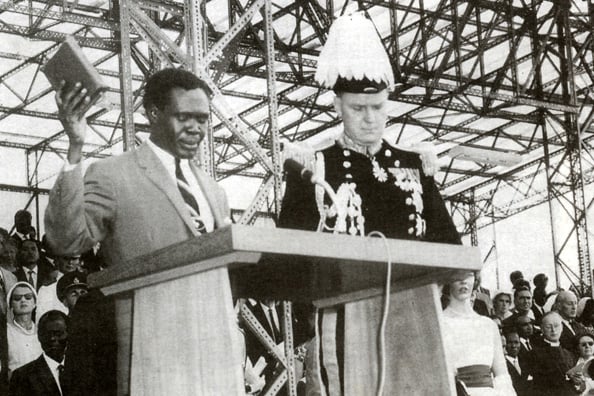

Milton Obote (L) swears in as prime minister of Uganda on Independence Day in 1962. PHOTOS/ FILE

What you need to know:

- In academia, politics, the media, civil society, religion, the civil service, and business, most Africans don’t have an emotional or philosophical connection to that abstract entity called the State.

Independence largely means nothing to most Ugandans today. As it falls on a Monday this year, the only value that it brings is by extending the weekend into Monday and giving many exhausted office workers much-needed rest.

The general population feels estranged from the State and particularly the National Resistance Movement (NRM) government.

The State, via the presidency, army, police, district party chairpersons and others, has come to represent all that robs or suppresses Ugandans.

On social media, it will be marked by “Happy independence day!” not so much because the sentiment is much felt, but because the norm on social media is for people to sound upbeat, hopeful, and celebratory.

Along with the current apathy toward independence, Ugandans and most Africans since they attained this milestone, have lacked a clear idea of what the State is and what purpose its serves in their lives and work.

As said, it is a symbol of oppression, deceit, and robbery for most Ugandans.

But philosophically, what does a State stand for in their minds?

It is a distant entity, allegiance to which is mostly an act of going through the motions and paying lip service to what is alien to them.

Some of this can be seen in the way the English Premier League, England’s main football championship league, has over the last 25 years gained such popularity in Uganda and elsewhere in Africa, and to most Ugandans of all social classes and ethnic groups, it is the closest thing to their hearts.

I mentioned in Twitter last year that, ironically, the English Premier League has done what the Organisation of African Unity, the East African Community, Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the African Union have tried but failed to achieve -- African unity.

The English Premier League is the force that has managed to create a shared emotional identity for Africans.

The other uniting factors for Uganda and other African countries is the main American social media platforms, from Facebook to Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and YouTube.

As with the English Premier League, it had to take something foreign to bring together by habit and intense engagement the otherwise scattered Ugandan population with little in common.

The popularity of social media, in particular, makes sense: Where the population is in a passive, top-down relationship with the Uganda government, with social media, millions of users actively scroll through their content feeds and post their own photos, videos, and thoughts.

President Museveni.

President Museveni is the best example of the core philosophical limitations of the African.

This is a man who, from the mid-1960s at Ntare School to University of East Africa in Dar es Salaam, to his present constant appeal for an East African federation, has always believed strongly in pan-Africanism and African statehood.

Or so it seemed until recently.

He put it well and honestly in a 2015 interview with a Kenyan television station when he said he is working for his children and grandchildren.

To start with, his children are now adults, have never lacked for anything material since Museveni came to power in 1986, they are married, with children of their own, and in material and financial terms are all doing well.

Even if Museveni were to die today, his children would not lack the means to fend for his grandchildren.

But even with 50 years of political activity and guerrilla warfare behind him, Museveni still views his primary purpose in life as that of looking after his adult children and grandchildren.

This hand-to-mouth mentality and collective culture explains most of the rampant corruption in Africa, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Be in academia, politics, the media, civil society, religion, the civil service, and business, most Africans don’t have an emotional or philosophical connection to that abstract entity called the State.

They see the state as a collection of institutions to work for, engage with, take advantage of, or in the case of the armed forces, avoid as much as possible.

An engineer, author of fiction novels, and friend Nik Twinamatsiko noted this on Twitter this week, October 4: “The ‘unreasonable’ man must, however, survive if he is to bring about that progress. The trouble with Africa is that, because we have always been strongly communal, we have also always had heavy penalties for ‘unreasonable’ people.

“An eccentric man is more likely to survive in an individualistic society than in a communal one. In the former, people will mind their business and let him be. In the latter, people will see his eccentricity as their most pressing business.”

“If Africa is to progress, it will have to become a more individualistic society and let eccentric people be.”

Here, Twinamatsiko captured the African attitude well. We live and think communally, view the public workplace and state as something to take from for the benefit of private pleasure and indulgence.

This cultural attitude is what native Ugandans brought into the civil service, Parliament, and other aspects of government service starting in the late 1950s and into independence.

The people of northern and Nilotic eastern Uganda have the highest sense of public duty and attachment to the State, while this attachment is lowest in Buganda, followed by western Uganda.

Perhaps this can be explained by the fact that the central and western regions of Uganda were organised kingdoms in the 100 years leading up to independence and incorporating them into the new nation-state Uganda felt to them like a demotion, while the northern and eastern Nilotic regions were at most chiefdoms, and so the bigger entity Uganda broadened them from tribal people to modern nationals.

Buganda remains, as it was six decades ago, the most self-consciously independent entity in Uganda, both in terms of independence from Great Britain and to the Republic of Uganda, and for this, tensions between the central government and the Buganda seat of authority at Mengo have never left since 1962.

Apart from having a weak sense of shared nationhood, Ugandan society is also weak in economic productivity.

What passes for large businesses are in reality termed small businesses in Western Europe and North America.

For example, in May 2000 under the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), the United States opened its market to 34 sub-Saharan African countries to export duty-free more than 6,000 products.

These 6,000 products encompassed almost all the product imaginable from Africa, from food and fruit, to garments and natural minerals.

There had not been such a golden opportunity since independence for most countries.

However, to date only four countries Nigeria, Botswana, South Africa and Angola, managed to meet their Agoa quotas. The four met their quotas mainly because Angola and Nigeria supplied petroleum, a commodity that will always be heavily in demand around the world, and Botswana and South Africa, on account of their precious metals and stones like platinum, gold, and diamonds.

Uganda’s and sub-Saharan Africa’s failure to meet their quotas under the Agoa terms revealed the bitter reality that Africa’s problem runs much deeper than we usually think, that is, having bad leaders and bad governments.

At the heart of our weakness is a lack of capacity. Our maximum production is not enough to meet the demands of major world markets.

The Chinese engineers building a new international airport in the Togolese capital Lome failed to find enough quantities of nails in the entire Togo and had to ship in nails from China.

We attained symbolic independence, but the facts have always disputed this formal status.

Uganda remains heavily dependent on the external world for its very sustenance, from aid from Western countries and Japan, to construction of our major infrastructure by the Chinese, from concessionary loans by the World Bank to remittances by Ugandans living and working abroad.

Domestically, there is nothing that can sustain the national economy.

This, then, is the answer to the much-discussed question: What is Africa’s problem?

Africa’s problem is that of structural weakness right to the core of society.