Prime

Achebe’s search for African identity

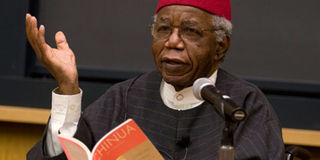

Achebe reads out one of his novels. Internet Photo

What you need to know:

When the tears finally dry up and it dawns on Africans and the world that no more magic will be coming from the trailblazer, people will ask where the next great African novel will come from.

When Chinua Achebe passed on, world leaders and local literary giants mourned him in ways that a man of his stature truly deserved. They called him “the great father of African literature”, “the godfather of the African novel”, “a humble man”, “a giant” (the first humble giant), “a statesman”, “a dissident”, “a nationalist”, “a warm man”, “a stubborn man”, “a trailblazer” and “an icon”, among many others.

Africa loves to heap praise on the dead, but the continent is agreed that Achebe deserved all that pean. On traditional and social media, those who have read his books remembered the man for producing some of the world’s most memorable and engaging titles, from his first major work, Things Fall Apart — which has been translated to about 50 languages and has sold over 10 million copies worldwide — to his last work, There Was a Country, published last year.

Literary critics like to label their subjects as “prolific writers”, but Achebe deserved, nay, earned that accolade. Over time, he wrote essays, poems, commentaries, children’s stories and engaging novels, works that cemented his position as one of the greatest writers of his time. He tackled the issues of Nigeria and Africa in a way that Africans, his biggest audience, understood before the world started to eavesdrop on the party then barged in and grabbed a chair.

The questions

But, what made this man special? What was so different in his story-telling to attract the attention of the world? To answer these questions, we have to study his mission, his driving force.

The greatness of Achebe’s works was borne out of the clear mission as to what his writing was to be all about. And it was clear from the start. At a time when African writers pandered to the critics of the West, Achebe was unapologetic over his perceived Afrocentricism, insisting that he wanted “to help my society regain belief in itself and put away the complexes of the years of denigration and self-abasement”.

Coming from a man who had switched from studying medicine to immerse himself in the world of letters, the direction of his writing could only have the outcome and impact that it eventually had in the world.

Right from the start, Achebe wrote to and for his people. He had Africa at the tip of his pen, yet still the wider world listened when he told tales of gods, black magic, and the malevolent forces of men.

His English was ‘New English’, a dialect in harmony with African sensibilities and culture, a medium of delivery bathed in native culture, clothed in native understanding and dried in native perspectives, notwithstanding that it was a European language.

To him, the African story could be told in English, only that the English had to be ancestral. By doing this, he managed to draw readers from all over the world while reinvigorating the pride and hopes of “his people”.

This careful play with words was captured by Indian scholar Dr Jayalakshmi Rao in an analysis of Achebe’s works. Dr Rao singled out The Arrow of God for exemplification, citing a paragraph in the book and writing it in “normal English”.

The excerpt is a speech by Ezeulu to Oduche: “I want one of my sons to join these people and be my eye there. If there is nothing in it you will come back. If there is something there you will bring home my share. The world is like a mask dancing. If you want to see it well, you must not stand in one place. My spirit tells me that those who do not befriend the white man today will be saying ‘had we known’ tomorrow.”

“Normal English”

The regular or normal English version of this conversation, said Dr Rao, would be: “I am sending you as my representative to these people... just to be on the safe side in case there is a new development. One has to move with the times or else one is left behind. I have a hunch that those who fail to come to terms with the White man will one day regret their lack of foresight.”

Through this sort of language, Achebe brought African oral aspects into the novel. He infused in his works African proverbs, similes, metaphors, and images. This is part of what set him apart as an African great man of letters at a time when other writers sought to be more eloquent in English.

But the language did something else as well; it endeared Achebe to his people, who now spread across borders. Today, most people, especially the political leaders of the continent, claim to have a thing or two in common with Achebe.

They come from the same continent as him; they come from the same country as him, they went to school in the university he studied, they have visited Boston where he stayed, they have attended conferences that he attended, they have read books that he wrote, they like the music he liked, they think like him....

And it was these same people, the scores who want to claim kinship with Achebe in all these tiny little ways, who were always in his mind when he wrote. He took their political struggles and frustrations and amplified them through his works.

When the White man arrived on the continent full of bravado and silenced the natives, Achebe gave them their tongue back through Things Fall Apart, a novel that made a mockery of the reaction of Africans to the British colonialists in Nigeria.

But the book was not just for the Nigerians; the events there were a carbon copy of what would happen in most African countries later on.

The clash of cultures, the tensions, the confrontations between strong-willed African men like Okonkwo and the White men, and the threat to African cultures was witnessed in Mwanza (Tanzania), Salisbury (now Harare in Zimbabwe) and even at the foothills of Mt Kenya.

In No Longer at Ease, Achebe introduced the major plague that has been the death of many African societies; corruption by those in public service, while A Man of the People called to question the state of African politics. All these were part of Achebe’s larger mission of giving back his people their pride and setting the African society right, but now the great humble giant is gone.

When the tears finally dry up and it dawns on Africans and the world that no more magic will be coming from the trailblazer, people will ask where the next great African novel will come from.

Forget Wole Soyinka (who is also good), Ngugi wa Thiong’o (who is equally good), Naruddin Farah (the fiery Somali), or Leila Abouzeid (the elephantess of Morocco). Forget about those, for they have already charted a course for themselves.

The continent now looks upon the new generation of writers to carry the mantle into the future.

Are there young African writers who have already placed one or two pieces of work that bear the mark of legends? Is there anyone who has defied the humdrum noise of the machines to break into our technologically mercantile world the same way the older writers — alive or gone — broke into the prejudices against Africa to tell the African story with flair and consistency?

Of course there are, but many will most likely not make it into this list because of the fear that the younger generation of African writers is losing its voice, drowned by what the world wants to hear or read.

Nevertheless, Brian Chikwava from Zimbabwe, Chimamanda Adichie from Nigeria, Niq Mhlongo from South Africa and Binyavanga Wainanina from Kenya come to mind. These four have shown that they have that remarkable touch with the pen, but what only few of them have shown is the magical touch possessed by the great ones who broke out in their 20s... but you never really know. Literature has a knack for surprises, as Achebe’s rise to the top attests.

Critics

As his literature flourished, some of his African peers criticised him for some of the choices he made in his writing career.

Ngugi, for instance, felt that Achebe ought to have stuck to writing in his Igbo language. To Ngugi, the fact that Achebe wrote in English was a setback to the development of African languages.

Others argued that the man lacked the grace and wit of his countryman, Soyinka.

The intellectual war on which language should be used as the medium in writing stories placed Ngugi on a direct confrontational path with Achebe and others.

Ngugi believed that language was used for spiritual division of Africans by the Europeans, and that it “carries culture, and culture carries the entire body of values with which we perceive ourselves and our place in the world”.

Achebe writes back

In response, Achebe claimed that Ngugi was not being completely honest and was using language to play politics, and that he used English “to infiltrate the ranks of the enemy and destroy him from within”.

Critics and scholars like Obi Wale and Abiola Irele joined Ngugi in his quest for the use of African languages, but challenges, starting from the limited audience of a particular language to political difficulties of privileging one language over another and cross-border linguistic tensions, among others, elbowed native African language from the continent’s literature in favour of, particularly, English and French.

Ngugi has written some of his works in Kikuyu but they have been translated to English for non-Kikuyu speakers.