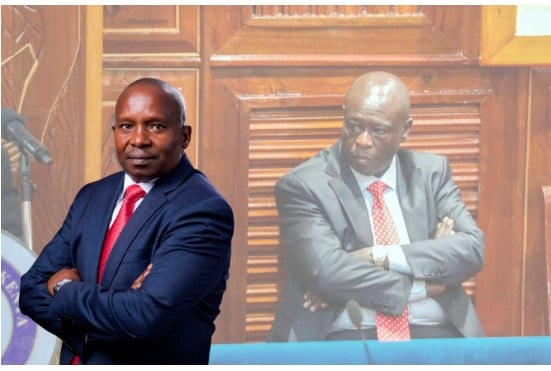

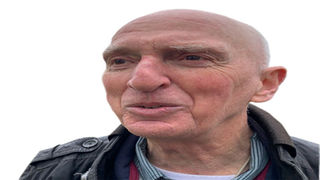

Daniel Nelson. PHOTO/COURTESY

|People & Power

Prime

Daniel Nelson speaks about editing The People and his arrest in 1968

What you need to know:

- In 1964, from a smoke-filled London newsroom, Daniel Nelson became sub-editor at the Uganda Argus, circulation about 20,000. In 1965 he became the first journalist to edit The People, replacing lawyer Fred Kakembo. Nelson remembers a wonderful independent Uganda: his children were born in Mulago hospital.

- But in October 1968 he was arrested in a sweep that picked up Abu Mayanja and Rajat Neogy too.Just days later, he handed over editorship to Ateker Ejalu though Nelson remained at The People until March 1969. Cathy Watson interviewed him.

How did you get to Uganda and The People?

I was married to Lesley, and we wanted to go to Africa. I wrote to about 30 newspapers and received yeses from a paper in Zambia’s copper belt and the Uganda Argus. We decided on the spot-on Uganda. The Argus was the English language daily. Edited by Charles Harrison, it was moving with the times, but rather slowly. Then I was offered the job of editor of The People and thought “That sounds exciting” and more in line with my politics. So, I moved. There was a lively press at the time with papers like Munno and Taifa Empya.

Who offered you the job, and why did they ask you?

The offer came from Erisa Kironde, chair of the paper’s board. I think they wanted an outsider who was neutral in Ugandan politics. Though I was eminently underqualified, I was an outsider. That was probably the key advantage. And I was young, enthusiastic and idealistic.

Was suddenly becoming editor daunting?

Yeah, very daunting. It was a weekly, so less daunting than if it had been daily. But the plan was to convert it to a daily, which we did. And it had talented journalists and production people. It was a pretty good team. But we were raw.

Where were Uganda journalists coming from then? From school, as you had done aged 18 in England?

Some had been at Makerere. But, yes, others had done the old-fashioned thing, worked their way up in the newsroom, like John Bagenda-Mpiima, who was an excellent hardworking reporter with a lot of inventiveness and courage. He tried his hand at everything. He could get out there and come back with a story, real classic stuff. It looks like you had good photographers and a nice dark room.

Nelson with The People journalist Luke Kazinja, who became DP MP for North Rakai in 1980, joined Fedemu, and later become an editor at The Star. PHOTO/COURTESY

The photographers had got cameras and learned on the job. The dark room was rudimentary, but serviceable. Most of the equipment was donated. The press was second- or third-hand from Norway. Type was set on old Linotype machines, and large headlines were hand-set with wooden blocks. I once wrote a front-page headline, and a printer said, “There’s four e’s in the headline and we only have two in that size. You have to change it”. Everyone worked around the problems to get the paper out.

How old were you when you became editor?

I was 22. Looking back, it was a classic colonial tale. Opportunities come because you are the right person in the right spot at the right time. Not because you’ve proved yourself in any way. You just have those chances. I’m forever grateful to Uganda. Who gets a chance to be on a weekly paper and convert it into a daily?

Did you have a plan when you took over?

The plan was to raise the circulation and give it some impact. The paper was functioning, but it had a very small circulation, maybe about 800 when we started. The plan was simply to get people to read it.

Did you succeed?

Yes. We cooked up stunts to boost circulation, like doubling the print run one day and dropping papers out of a plane, and inviting readers to vote for Sports Person of the Year: we had to cancel that contest when we noticed that the “winner” was based on a large number of postcard votes in the same handwriting. Some schemes were actually very good, like a double page pullout that was an open-to-all education course on useful topics, such as how to write a job-application letter. We’d run a subject for several weeks and give certificates. Makerere’s extra-mural department provided much of the material. Old-time journalists said “That doesn’t belong in a newspaper”. But people liked it, and it pushed circulation up.

What was The People?

It positioned itself as nationalist because the Argus was foreign-owned by Lonrho, in the East African Standard group. The slogan on the banner was “For, about and by Ugandans”. The editorial philosophy of most other papers was grounded in adherence to a religion or Buganda. But it also saw itself as supporting the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC). It wasn’t a party paper in that it publicised every party event or ignored Opposition parties. But there was no doubt that it was on the side of UPC.

What were the big stories?

The DP [Democratic Party] was still hoping to get into power one day. The kingdoms were a hot topic. Otherwise, there were stories about the economy, business, sport, health, social affairs and “development projects”. The worst headline I ever wrote was “War Is Declared” in huge type. It was about a crackdown on market traders who were secretly attaching weights to their scales – a shamefully sensational headline.

How would your day go?

It was an absolutely crazy job, especially for someone with young children. I’d go in early, work all day, get home late and be working at home. It was around the clock. There was such a lot to do. I felt the need to write, rewrite, read everything.

Daniel Nelson interviews Dr Emmanuel Lumu (centre), the first minister of Health in independent Uganda. PHOTO/COURTESY

And the staff worked long hours, too. I remember once, some staff arrived a bit late, and I said, “We’ve all got to try to be on time”. And one replied, “Well, I got up at half past four to walk here in pouring rain.” There was incredible commitment.

Did you manage to send the paper upcountry? Did it get down to Kisoro and up to Kitgum?

Jack Kironde, the managing director, arranged all that. We didn’t get it everywhere, and buying a somewhat flimsy English-language paper was not a priority for most people. Some probably thought they ought to read it, even if they didn’t share its politics. The circulation was never as good as it should have been, but it went up quite a lot, and we got advertising, including, of course, government contracts. Once a North Korean representative came with a briefcase of banknotes to pay for an unreadable double-page spread congratulating the Dear Leader!

Did the paper support itself from sales and advertising or need something from the party? Can you remember?

It’s not only a question of remembering, it’s also a question of how much you know. I was working out how to be an editor of a paper, and that was full-time. Jack Kironde was an honest guy. So if he told me we could or couldn’t afford something or someone, I accepted it. We had budgets, of course, and targets, and I knew whether readership or advertising was up or down. But looking back I don’t think I knew about the overall finances, about whether we were paying our way. There were all sorts of open and hidden subsidies, really, starting with the equipment.

Did Obote take a personal interest?

Yes, because he knew about the importance of information. But radio was important, and the actual sheer politics of overthrowing the Kabaka, keeping the UPC together, running the government, building infrastructure was top priority. Of course, he followed the paper. But I was never summoned and told “This is crucially important. Do this. Do that. Otherwise, there will be consequences”.

So initially things were easy. Then in 1966 Obote became president.

Yes. People were upset and angry in Buganda, because the Kabaka was overthrown, and we were in the heartland of where it mattered most. Also, the political balance established at Independence had been broken, force used, and the prime minister had assumed the presidency. We had a cartoonist, and one day we agreed on a cartoon that was anti-Kabaka. That’s how naïve I was. Intervening for the only time on an editorial matter, Jack Kironde said, “Danny, you’re not going to run this cartoon, are you?” And I said, “Yes, that’s the plan”. And he said “If you do, this place will be burnt down and possibly worse”. I had to really think and finally agreed not to publish it.

When did Idi Amin become somebody you had to pay attention to?

Amin would be in the Uganda Club, along with ministers and journalists, hangers-on and people who wanted influence or business. So, you’d sit with him and have a few beers. Of course, people were politicking and manoeuvring. But for us, who were not directly involved in affairs of state, you chatted and picked up the gossip. Amin might say something a bit absurd, and you’d laugh. The difference after the coup was that he would say something, and people would say “Yes sir” and often implement it. So, yes, I was aware of him but he wasn’t part of my life as an editor. Everyone was always wary of the army, of course. They didn’t have a very good reputation. If you overtook an army truck, you did so at your peril. But the army wasn’t at the forefront all the time except when they stormed Lubiri and intervened in Congo. I wasn’t expecting a coup.

Did you feel part of a political project?

Definitely. It was Independence. It was a wonderful, wonderful time. There were dangerous cracks, such as the imbalance left by the British with educated southerners and militarised northerners, and the divisions about kingdoms and how Uganda should be governed.

A section of Kampala Road in 1974. The major buildings are, left to right: Diamond Trust Bank, Uganda House, Charm Towers (then under construction), and Barclays Bank, now Absa. PHOTO/FILE

But then there was this overall feeling of more schools being built, money going into hospitals, improvements coming. And I suppose as an outsider, and rather young and idealistic, I thought more about the great things that were going on rather than the potential conflicts erupting into something deadly serious. It felt to me like the colonial dam had burst, and development was gushing forward.

Where you on top of the politics?

Looking back, I now realise that all I knew was the tiny bit in which I was involved. For example, I completely missed religion as a fault line because I’m not religious. I completely missed the significance of the fact that DP was predominantly Catholic and UPC predominantly Protestant. I missed the role of the Muslims. Amazing to think that you could run a daily paper and get such matters completely wrong.

What was life like?

It was exciting, stimulating. I still think it was as close to paradise as I’ll ever get. Like many, I was attracted to Africa and Asia partly because of the chance to participate in radical change in contrast to the glacial pace of change in our own countries. I was young, with a young family, in a great job, at a time of optimism and a sense of future. Makerere was golden, with academics, writers and artists such as Ali Mazrui and David Rabadiri. Uganda was the home of Transition, still perhaps the best magazine Africa has produced. It was Rajat Neogy’s baby.

Nelson with Neogy. He and his wife, Barbara Lapcek, shone bright in 1960s Kampala. Lapcek founded Nommo Gallery. PHOTO/FILE

He was a one-off, and Transition attracted writers such as V.S. Naipaul, which added to Kampala’s intellectual lustre. You could sit on a veranda in a restaurant and have a Nile perch and chips, discussing Africa and the world. You seemed to be at the cutting edge. At Susanna and other nightclubs, you were as likely to share the dance floor with the minister of Defence as with a waitress. Cinemas showed “must see” films. It was a lively fulfilling life if you had something in your pocket. Maybe some of us got more caught up in that than in looking at the undercurrents of discontent.

Tell me about the night you were arrested.

There were heavy steps on the roof. Then there was a great hammering at the door. I opened it so they didn’t smash it, and they said, “You are under arrest”. Then the children and [my wife] Lesley appeared, and one of the kids said, “Don’t take our daddy away”. The soldiers searched the house looking for weapons. I said, “I haven’t got a weapon. I can’t fire a gun”. The worst is when you’re pushed into the back of a Land Rover, and you are thinking “What’s going to happen to my wife and children?”

You weren’t expecting it? You didn’t think “it was that article I wrote”?

I had no idea what it was about. Abu Mayanja was already in the Land Rover. In our night clothes, we were tied up and taken – via the President’s Lodge, where a surprised guard peered into the vehicle and asked me what was going on – to a barracks. When I was made to lie on the floor and hit with batons, I was particularly nervous because the radio was broadcasting news from Rhodesia about Ian Smith, and I thought, “This is going to make them beat me even harder”. I’m not sure they were even listening. Later I got a doctor’s certificate, which stated “lateral abrasions to the back and buttocks”.

Former presidents Milton Obote (left) and Idi Amin. PHOTOS/ FILE

After a few hours, I was shuttled to Luzira [prison] and knew I was safe. The army were unpredictable; in a barracks, anything could happen. In contrast, the police were disciplined. I don’t mean that everyone the police arrested was safe. I’m sure they did some bad things. But they offered me a drink, and I thought “It’s over. People will come and get me.” Many friends were nervous, though, because they thought they might be followed and didn’t know what was going on. After some hours, Erisa Kironde and one or two others came, and I was released. Perhaps Obote said, “Let him out”.

What had triggered your arrest?

I went to see intelligence chief Akena Adoko and asked, “What was all that about?” At first, he claimed not to know, but I spotted a small plate from our house under his ashtray. So obviously he did know. Then he said that it had been the first exercise of a new special force and instead of arresting Rajat Neogy, they picked up Daniel Nelson because both our names began with N. This sounded unconvincing.

Then you went to see Obote at State Lodge.

Yes. He was non-committal. I assumed my detention was because of a split in the UPC between the Obote faction and another led by Grace Ibingira. I was more answerable to Obote than to anybody else. He never told me what to print, but he was the boss.

Left to right: Uganda’s Finance minister James Simpson, minister of Justice Grace Ibingira, Prime Minister Milton Obote, UPC secretary general John Kakonge and US President John F. Kennedy during a meeting at the White House, USA, on October 22, 1962. PHOTO | COURTESY

I had opposed preventive detention in an editorial, describing it as bad in principle: you shouldn’t arrest people before they do something. Perhaps my arrest was a warning that the government was prepared to take action against those it considered unsuitable.

Was that the beginning of the end for you?

We were already working towards an all-Ugandan staff but it speeded up the process of finding a Ugandan editor. I handed over to Ateker Ejalu just 10 days later, though I stayed with the paper for several months. It all happened fast. The golden period was over. Lesley and the kids were unsettled. When the coup happened I was in the UK, and the Financial Times asked me to write a profile of Idi Amin. I wrote a well-informed column about Amin but finished it with a flourish, confidently forecasting “he will not last long in power”. Wrong again! (laughing) But as a friend pointed out, nobody remembers what journalists predict.

Historical coda

Abu Mayanja was kept in prison for a year, and Neogy for four months in solitary confinement where he developed schizophrenia. Ejalu moved to the Argus in 1970, and Charles Binaisa became editor of The People but perished in a car accident. Daniel Nelson went on to work for West Africa magazine, Financial Times, Press Foundation of Asia, Down to Earth in India, Far Eastern Economic Review in Hong Kong, Daily Star in Bangladesh, Gemini News Service and as a consultant to international NGOs and UN agencies. Today he runs www.eventslondon.org. Cathy Watson reported from Uganda 1986-94 and started Straight Talk in 1993.