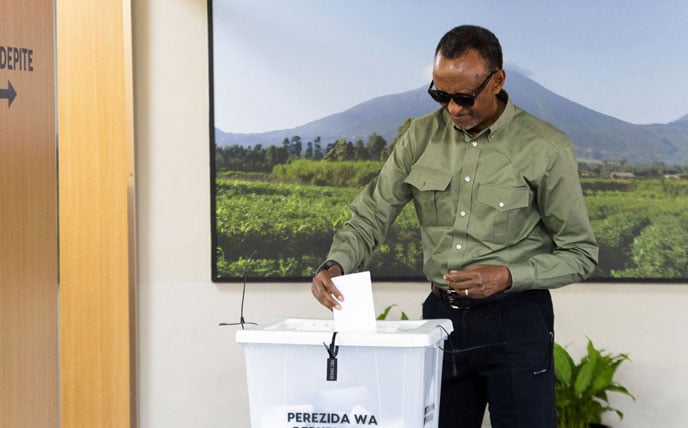

Rwanda President Paul Kagame votes during the presidential election in Kigali last month. Photo | REUTERS

Twenty-one years after Mr Paul Kagame debuted in the Rwandan presidential elections, many observers have asserted that the question is no longer if he can secure a victory but how big the percentage can get.

In 2003, Mr Kagame won with more than 93 percent of the vote and replicated the same in 2010 and 2017, defeating the same pool of challengers.

But 2017 will perhaps remain crucial in Rwandan history because with Mr Kagame’s reign about to end due to the two-term limits that had been inscribed in the Rwandan constitution, a controversial referendum that was predictably in favour of former National Resistance Army (NRA) spy officer, showed that 98 percent of those who participated voted to make it possible for Mr Kagame to run for an additional seven-year term and then two – which means he could stay in power until 2034 and beyond.

In terms of the Great Lakes region, Kagame wasn’t the first to eliminate term limits because in 2004 the National Resistance Movement (NRM) led by President Museveni moved to remove the two-term presidential limits that had been put in the 1995 Constitution – and if followed would have ensured that Museveni’s reign would have ended in 2006.

Museveni entrenched himself in power further in 2017 when his party edited presidential age limits out of the Constitution that had put the cap at 75 – because had the law remained, Museveni wouldn’t have stood in the 2021 General Election.

Peace talks. Left to right: Presidents Sassou Nguesso (Congo Brazaville) Yoweri Museveni (Uganda), Joao Mauel Laurenco (Angola), Paul Kagame (Rwanda) and Felix Tshisekedi (DR Congo) hold hands in solidarity after signing a Memorandum of Understanding between Uganda and Rwanda at the Presidents Place in Luanda , Angola on Wednesday August 21, 2019. PPU PHOTO

After removing both term and age limits, the best Museveni has done in the presidential election was in 2011 when he got 68 percent and in the last election, he got 58 percent as his hold on power has become increasingly challenged by a youthful Opposition.

Weak opponents

Yet for Kagame, his presidential elections figures have been on an upward trajectory and this was evidenced when he secured 99 percent of the vote in the recent elections after competing with two candidates – Frank Habineza of the Democratic Green Party and independent Philippe Mpayimana.

Mr Asuman Bisiika, who once lived and worked in Rwanda, does not think much of Mr Kagame’s opponents in the last election. Like many followers of Rwanda’s politics, he thinks they were stooges who did not pose any meaningful threat to Mr Kagame’s stranglehold on power and matters Rwanda.

Mr Bisiika actually questions the entire political and electoral set-up in Rwanda, saying the opposition was falling all over itself in order to support Mr Kagame’s candidature.

“All the major parties in the political opposition endorsed his candidature. It is like the National Unity Platform (NUP), the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), the Democratic Party (DP) and the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) supporting Mr Museveni’s bid for re-election, leaving only the like of Mr John Katumba as his opponent,” Mr Bisiika argues.

Mr Katumba, then 24 years old, was one of the 10 people who challenged Mr Museveni for the presidency during the 2021 General Election. He was an independent candidate.

Other candidates in the race were Mr Robert Kyagulanyi of NUP, Mr Patrick Oboi Amuriat of FDC, Maj Gen Mugisha Muntu of the Alliance for National Transformation (ANT), and Mr Nobert Mao of the Democratic Party (DP).

The others were Mr Willy Mayambala, Mr Fred Mwesigye, Gen Henry Tumukunde, Mr Joseph Kabuleta and Ms Nancy Kalembe who were not aligned to any political parties or organisations.

Talking detractors

Just like in Uganda where Mr Museveni’s rallies are normally filled with people singing praises for the President who has been in power since 1986, Mr Kagame’s rallies were also filled with thousands of supporters who sang praises slogans and shouted chants.

President Museveni and his Rwandan counterpart Paul Kagame. Photo | File

Mr Kagame predictably was sure of success, telling Rwandans at one of the rallies thus: “I have come to say thank you in advance. May you keep focus on the important things and not be distracted by the detractors.”

Who could be the detractors that Mr Kagame was talking about?

After winning the elections, Mr Kagame gave indicators of who his detractors could be when he dispatched a message on X (formerly Twitter) in which he thanked countries whose leaders had congratulated him upon obtaining another term in office.

The notable leaders that he thanked for congratulating him ranged from Barbados, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Cuba, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Oman, Qatar, Senegal, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Switzerland, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, Venezuela to Zambia.

Mr Kagame’s relationship with the West has recently been defined by the deal he had struck with the Conservative Party (CP) in the UK in which the tiny central African country was going to get millions of pounds as part of the deal to receive thousands of asylum seekers from the UK.

Legal challenges in the UK which were hinged on Rwanda’s atrocious human rights record prevented people from being dispatched to Kigali, excluding four individuals who went under a voluntary scheme but the deal seems to be dead after the CP was ousted from power by the Labour Party.

Mr Kagame, however, did not thank any leader from the West, which got most people reading into this. For some schools of thought, this spoke volumes about the estranged relationship with the West, most of which viewed the elections as heavily discredited on account of the Rwandan government’s decision to bar several opposition candidates who would have possibly given Mr Kagame a run for his money, from participating in the elections.

However, Mr Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, a political scientist and researcher who lives in both Uganda and Rwanda, thinks that people are reading too much into Mr Kagame’s tweets.

“I do not see what his decision not to mention countries in the West says about Rwanda’s relations with the West. If he did not mention them, he had no reason to mention them I presume. I saw what he tweeted. He was thanking those countries that had congratulated him. By then those countries had not congratulated him,” Mr Golooba-Mutebi says.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame campaigns in Kigali last month. Photo | REUTERS

The bans

Earlier this year, it should be remembered, a Rwandan court barred Ms Victoire Ingabire from challenging Mr Kagame on grounds that she had been convicted of terrorism and genocide denial.

Ms Ingabire, a ferocious critic of Mr Kagame who has been in leadership since 1994 following the end of the genocide, was sentenced to 15 years in prison, but she served eight years following “a pardon” from the Rwandan strongman’s administration.

Ms Diane Rwigara, another would-be opponent for Mr Kagame, was also barred from standing by the electoral body in Rwanda on account that she had failed to show evidence that she had no criminal record. Though Ms Rwigara insists that she was born in the country, the authorities in Rwanda said she couldn’t stand because she failed to prove that she was Rwandan by birth.

It has always been quite difficult to understand why Mr Kagame would seek to practically be the only big bull in any electoral kraal in Rwanda. Ambassador Harold Acemah, who retired in 2007 after 37 years in the Foreign Service, is one of those who find it baffling that Mr Kagame “fears” to come up against credible opponents.

“Rwanda is one of those countries in Africa which are highly regarded, especially in terms of economic development. I think President Kagame has done a wonderful job. The country seems well-organised and well-focussed, but they need to open the political space for all the players in the country. Mr Kagame is on solid ground. He should not be silencing any of the citizens,” Mr Acemah argues.

The Tshisekedi/Congo factor

Relations been Rwanda under Kagame and the RPF and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) date back to the 1990s when the Congolese army fought alongside Rwanda’s army under Juvenile Habyarimana.

According to “ICG Democratic Republic of Congo Report Nº 3”, which was published by the online information source on global crises and disasters, Relief Web, RPF’s victory led to the subsequent exile into the eastern DRC of about one million Hutu along with their leaders along with men and officers of the defeated army.

It was largely in part due to the need to annihilate that force that Rwanda under the RPF fought alongside Kabila’s force in the 1996-1967 war that saw President Mobutu Sese Seko removed.

That, however, did not eliminate the threat posed by the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) and those that Rwanda accuses of having participated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

The emergence in April 2012 of the March 23 Movement, a predominantly Tutsi militia that is fighting against the government in Congo, has since seen the governments in Kinshasa and Kigali trade accusations of harbouring each other’s rebels. Kigali accuses Kinshasa of training, equipping and financing the FDLR while Kinshasa accuses Kigali of doing the same for M23.

President Felix Tshisekedi has in recent time been more vocal in his accusations against Mr Kagame.

“I have always maintained that you have to build bridges rather than walls,” Mr Tshisekedi said. “That does not constitute an opportunity for neighbours to come and provoke us. I hope that Rwanda has learned this lesson, because, today, it’s clear, there is no doubt, Rwanda has supported the M23 to come and attack the DRC,” President Tshisekedi said in June 2022.

His remarks followed a resurgence of military activity by the rebel outfit which is accused of causing havoc in eastern DR Congo.

Such outbursts would make him one of the latter’s detractors. Little wonder that he was not mentioned in his X message.

It should, however, be remembered that Mr Kagame did not congratulate Mr Tshisekedi when he controversially won a second term in office at the end of last year. The Congolese leader returned the favour.

Perhaps in sending a warning to his “detractors” during the colourful rallies he has been holding across Rwanda Kagame has kept on reminding everyone who has cared to listen that Rwanda has built a force to reckon with.

“We have built our knowledge and capabilities. Our knowledge and skills have expanded,” he said.

Was that just rhetoric on a campaign rally? Or will it define the way Mr Kagame approaches issues as he starts his last first five-year term of a possible two?

Mr Bisiika does not expect a change in the man or his policies both at home and in the region.

“You do not expect him not to contest in 2029. So to talk about the region is to brace yourself for his permanent presence. He does not seem to be the kind of person who would change. The neighbourhood should get used to his presence,” Mr Bisiika says.

Mr Golooba-Mutebi says it will depend on which country he is dealing with. He says he is aware that Burundi and Rwanda are working on mending fences, but that relations with Rwanda and DR Congo are unlikely to be fixed anytime soon.

“Congo is a completely different case because the relations between Rwanda and Congo have been soured as a result of third and fourth parties (M23 and FDLR). Unless those third parties are dealt with, I don’t see that there is going to be a lot of change,” Mr Golooba-Mutebi says.

If what Mr Bisiika and Mr Golooba Mutebi say is anything to go by, it appears that Rwanda and the region will be having more of the same old Paul Kagame and his policies.