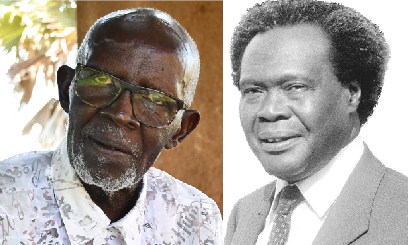

Retired Col Tonny Otoa (L) and former President Milton Obote. PHOTO|TOBBIAS JOLLY OWINY/ FILE

On July 27, 1985, Gen Tito Okello Lutwa and Gen Bazilio Olara Okello brought the curtain down on the Apollo Milton Obote II regime. Bazilio Okello was at the time the commander of what was then known as the Northern Brigade of the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), while Tito Okello was the army commander.

Retired Col Tonny Otoa, a former member of Obote’s government has spoken out, detailing the mistakes that the president repeatedly committed that cost him his seat twice, first in January 1971.

Otoa in both governments was one of the closest army officers to Obote. Below is his account of events that led to Obote being overthrown by former president Idi Amin in January 1971:

In 1962, the British colonialists relinquished independence to Uganda and left it with a well-organised, well-armed, and logistically perfect army. But hell broke loose for Obote in 1969 once he mounted a move to shift the economy to the left.

It, unfortunately, did not please the capitalists, people who had a lot of interest in our economy such as the British and the Americans.

Most of the companies that were here at that time were owned by the big companies in Europe, such as Cooper Motors, Gailey and Roberts, and some of them owned tea estates.

They were not pleased. They started exploiting the weaknesses in the army; the tribalism that existed. The army was complaining, some sections of the army claimed people of this side were highly placed in the army; and those capitalists started planning on how to get Obote, who was frustrating their business, replaced.

Uganda was giving Britain a lot of money. All banks belonged to the British and they wanted to find somebody whom they thought could dislodge Obote.

Five years after independence, Obote was still struggling to consolidate his army, which had been rocked with division and tribalism.

Obote had been advised by his military council to go slow with the move to the left since intelligence had indicated that the capitalists infiltrated the military to influence some of the senior military officers to topple the government.

We did not maintain the standards of an army. Recruitment became much more political and that made balancing the army very difficult. Soon, tribalism came in, and the capitalists exploited that sort of thing.

In the mix of a divided army and the rise of a few elite army commanders appointed by Obote, Amin had not only started seeing insecurity in his job and thinking that he might be replaced, but he had also got into problems when he embezzled Shs3 million that had been disbursed for military logistics.

Amin started getting sentimental and tribalistic and started influencing officers in the army and his other allies, include some people in Buganda, saying the army was only composed of the Acholi and the Langi. He capitalised on the Lubiri raid of 1966, saying the Langi were responsible.

The division in the army only increased, with everyone fearing the other, and eventually, our army did not maintain its unity and strength. Amin started exploiting this gap by influencing army promotions and also by politically establishing army battalions in Moroto, Gulu, Mbale, etc.

Being the chief of staff at the time, Amin began to introduce strategies, including promoting and bringing on board new military commanders who were his loyalists. This culminated in the coup of 1971.

At the time of the coup, Amin was very desperate. He had misappropriated some funds that had been allocated to be used in buying stores for the Uganda army—about Shs3 million—and it was a lot of money.

An investigation into the claims that Amin bought weaponry and sent them to Masaka, Moroto, Gulu, and Jinja revealed that there was nothing procured and delivered to the said bases.

Classified information indicated how Amin plotted and killed Brig Pierino Okoya in 1970 since he had been rumoured to replace him once he was sacked and arrested.

At this time, President Obote was slowly immersing himself in a murky political environment. Parts of the classified information that was shared with Obote revealed that the capitalists, backed up by Amin, wanted to oust Obote.

We asked him to quickly get rid of Amin and replace him with other elite officers. Politics was not very good for Obote because the West didn’t want him.

Obote knew that there was trouble within his army, but instead, he focused his attention on politics because, to a civilian as he was, politics was more important than army affairs as long as the soldiers were feeding him well and telling him good things. But inside the army, things were bad.

The evening before Obote flew out of the country to Singapore for the Commonwealth Heads of States Summit, Amin came and met the president at State House Nakasero.

That evening, I was in the president’s company and we were having a meeting. Amin arrived in shorts and sandals. Once he arrived at the door, he went on to his knees and crawled up to the feet of Obote.

‘Look at me just the way I am. I kneel before you here; an apology wouldn’t be enough if I ever wronged you and the system. But do you believe and do you think I can ever betray you and overthrow your government?’ Amin said. All of us watched in silence.

Earlier in the day, Obote had instructed the army council and the Internal Affairs minister at that time, Basil Bataringaya, to arrest Amin.

However, Amin’s display of utmost loyalty and remorsefulness convinced Obote that all was well.

The following day, Amin summoned the army council in the absence of Obote, who had already left for Singapore.

Amin exploited the situation very fast. He summoned the army council composed of battalion commanders and senior members of the Ministry of Defence. But Amin came to that decision with the help of the Israelis; they were the agents of the Americans in the army.

The Israeli forces were the ones training the Uganda army. They were everywhere in the infantry, air force, and artillery, and he used them to overthrow Obote’s government.

According to him, David Oyite-Ojok (then a Major), who had been given instructions by Bataringaya to arrest Amin was a junior officer. A junior officer could not effect the arrest of his or her senior, by British standards.

Once he overthrew the government, Amin purged the army and anybody who was a Langi or Acholi was targeted.

For nearly four or five years, Amin struggled to rebuild an army amid the pressure we were giving him from exile.

When we returned from exile, there was nothing. The economy had collapsed; all the army barracks were gone; only buildings were left. Weapons were very few.

At the camp

Life in exile in Tanzania was one key test for Obote’s politics.

The tribal sentiments and hatred between the two tribes were carried forward to exile. The Acholi and Langi did not see eye-to-eye in exile. We were so badly divided that no one spoke to the other, particularly Otema Alimadi and Obote, who hated themselves.

This division failed our efforts when we mounted an attempt to dislodge Amin in 1972. The attempted ousting of Amin caused a regression in relations between Tanzania and Amin’s government.

However, once the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) asked Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere to leave Amin alone, Nyerere heeded the OAU’s call and disarmed the Ugandan exiles.

When we got disarmed, we turned into proper refugees and were handed over to the UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees]. We were taken to Kigwa Camp in Tabora, where all the elite – architects, engineers, etc. – lived in the same condition and suffered together.

Nyerere considered the suffering of Obote and his people and decided to issue employment to those who were learned and qualified.

We got jobs. The late Anthony Okwenye was placed at the Tanzania Audit Corporation, and I worked with the Dar es Salaam Development Corporation. Others were employed as teachers, medical doctors, etc.

But because the rest of the unlearned remained in the camp – the majority being the Acholi with the Langi making less than 10 percent – Tito Okello, then a senior military officer, started mobilising and inciting his kinsmen.

He told them that Obote was tribal and that he had made the Langi employed in Tanzania since they were learned. He openly asked if they did not see Langi exiles employed in Dar es Salaam, Moshi, Arusha, and Mbeya.

So it was easy for them to carry the same feeling when we returned to Uganda upon ousting Amin in 1979.

In Part II next week, read about the military blunders that cost

Obote his second government.