Prime

Would bringing back Constituency Development Fund save MPs?

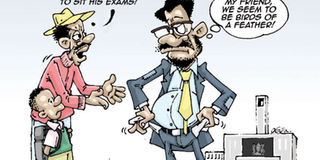

Pressed for cash, some MPs are either selling their political souls or shaking down the government. Illustration by Chrisogon Atukwasize

What you need to know:

Breaking down her expenses in an interview with this newspaper, Mukono Municipality MP Betty Nambooze says she spends Shs10m per month to attend Parliament, pay her employees, run her education foundation, service an ambulance she bought for constituents and contribute towards funeral and wedding expenses.

Parliament’s visiting room is often teeming with people, some of them constituents. They hope MPs hold the answers to their difficulties.

Citizens come to MPs with demands varying from major constituency problems such as collapsed bridges to personal problems like medical expenses.

A few weeks ago, Mr Ramazan Asaba, a native of Katikamu North, was at Parliament to check on his area MP Abraham Byandala and Alex Ndezi (PWDs, Central). He was full of praise for Mr Byandala whom he said helped him with building a house, marriage and medical expenses.

“I want him to give me Shs1 million so that I put up my own projects and stop stressing him,” was Mr Asaba’s latest demand to his MP.

For Mr Godfrey Sekatonya, his is a land resettlement project which he wants addressed by MP Samuel Semugaba (Kiboga West).

Such are the hassles MPs have to put up with on a daily basis. These demands often weigh heavily on MPs, leaving them under financial duress.

For instance, Mr Wafula Oguttu, the Leader of the Opposition in Parliament, says he took a Shs200 million loan when he made his way to the House in 2011.

He says a big chunk of that money was spent on repairing boreholes, buying culverts for roads, scholastic materials for schools, pads for girls and cycles for persons with disabilities (PWDs) in his Bukholi Central constituency of Mayuge District.

He currently forks out Shs7 million per month to service the loan.

At the same time, Mr Oguttu says every month he spends between Shs6 million and Shs10 million on repairing the more than 300 boreholes in his constituency.

In the neighbouring Butaleja District, Bunyole East MP Emmanuel Dombo says he spends more than Shs30 million on repairing boreholes during the drought while maintenance of some boreholes can require Shs2 million.

Breaking down her expenses in an interview with this newspaper, Mukono Municipality MP Betty Nambooze revealed that she spends Shs10 million per month to attend Parliament, pay her employees, run her education foundation for underprivileged children, service a Shs68 million ambulance loan she bought for constituents and contribute towards funeral and wedding expenses.

In the book: Theories on the Practice of Democracy: A Parliamentarian’s Perspective, Aruu County MP Odonga Otto makes reference to an unnamed MP who took out a Shs300 million loan, invested it in a savings and credit society in the constituency, but which money was never paid back, leaving the MP on the brink of bankruptcy.

Paid off

MPs such as Mr Oguttu, however, are lucky their gambles may have paid off. Colleagues in the Ninth Parliament including MPs Yahaya Gudoi, Florence Kintu, Nakato Kyabangi, Joseph Balikudembe, Simon Peter Aleper and Muhammad Nsereko have found themselves in court over money.

These six MPs, who are just the tip of an iceberg, took loans which they failed to clear on time. They blame failed business deals for their woes.

In 2012, Daily Monitor quoted sources on the Parliamentary Commission, the body charged with the administration of the House, revealing that more than 40 legislators are saddled with very heavy debts. MPs are cagey while discussing their financial plight and it is difficult to map whether their woes are due to constituency pressures or their affluent lifestyles.

But some of the MPs’ cash problems are clearly due to spending in their constituencies. For instance, in the Ninth Parliament, nine MPs have dug into their own pockets to purchase ambulances for their constituencies, a responsibility which ideally should be discharged by the government.

Mr Oguttu says there is a disconnect between the central government in Kampala and the local service distribution units, a void that MPs dig deep into their own pockets to fill. Some say this would otherwise have been taken care of by the Constituency Development Fund (CDF).

“The government cannot have maintenance of schools at the centre; that can only be done at the district or at the constituency. Since I became MP, they (government) have only built two [school staff] houses,” he said. “Kampala cannot repair a school and they will never. They have never repaired a hospital. The hospitals that [ex-president Milton] Obote built have never been repaired. With a CDF, there would be no road without a bridge, no school without paint,” Mr Oguttu says.

Speaker of Parliament Rebecca Kadaga says MPs have to contend with a situation where they are viewed by their constituents as “the government and are thus expected to perform executive roles”.

“In our society, people look at the MP as government. They cannot see the President. So you (the MP) are the person they see. If they want a loan, it is you, if they want a hospital, it is you. We need, as a country, to educate our people about the roles of government,” Ms Kadaga says.

Prof Nelson Kasfir, who researched about Uganda’s disbanded CDF, says MPs have a better understanding of the problems in their constituencies than central government bureaucrats and would be better placed in tackling them.

And considering the financial demands that MPs have to contend with, Constituency Development Funds are being embraced as a means to plug the funding void left behind by the government.

By 2002, one-quarter of 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa had adopted some type of CDF, according to a report: Why CDFs in Africa? Representation vs Constituency Service by South Africa’s Centre for Social Science Research.

In Uganda, the first proposal for a CDF was made in 1997 by the then Samia Bugwe North MP Aggrey Awori who suggested that each MP be given Shs2.4 million as CDF per month.

“There was no safety net for the constituents. It was a question of intervening on poverty in the constituency to cater for issues that were not catered for in the Budget,” says Mr Awori.

Though Awori’s proposal was rejected, the government later agreed to a ‘mobilisation fund’ of Shs2.5 million.

But increasing financial pressures on MPs in the early 2000s led to renewed calls for a CDF - which the government eventually yielded to by introducing a Shs10 million facilitation for each MP in 2005.

In a study titled: In Name Only: Uganda’s Constituency Development Fund, parliamentary researchers Nelson Kasfir and Stephen Twebaze learnt that the CDF was meant to be a “relief” for MPs from “constituent financial pressures ”.

“It was promoted explicitly to reduce the costs of constituency service while implicitly intended to help incumbents maintain voting support,” the paper explains.

Mr Pereza Ahabwe, the former Rubanda East MP, who was the vice chairman of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee when CDF was introduced, says indebtedness and financial pressures were high on the agenda when a CDF was approved.

The Kasfir and Twebaze research traced MPs’ financial woes to an increase in campaigning costs coupled with legislators making unrealistic promises in the exuberance of campaign season.

The study further blamed the proscribing of political party activity in the early Museveni era – leaving MPs to fight a solo fight – and a culture where voters offered themselves to the highest bidder for the high campaign costs which left MPs out of pocket.

Speaker Kadaga agrees with the study, affirming that the problem is grounded in the commercialisation of politics in Uganda.

To curb this financial expenditure during campaigns, there is an ongoing study by the Uganda Law Reform Commission to find ways of banning politicians from fundraising, reveals junior Justice minister Freddie Ruhindi.

Before it was scrapped, the CDF was riddled with implementation problems. A study that assessed the CDF revealed that little thought was put into how it would work.

When guidelines such as a requirement to spend the money on projects not catered for in the national Budget and approved by a constituency committee were hurriedly passed, they were never followed, resulting into abuse of the fund, according to a Uganda Debt Network (UDN) report.

When the cash was first released in 2006, more than Shs3 billion was unaccounted for, according to a review by the Auditor General.

A 2007 UDN study revealed that 73 per cent of MPs could not identify projects they had sunk the money in, with some admitting to having spent the cash on alcoholic drinks.

Another study by the African Leadership Institute (AFLI) under its Parliamentary Scorecard report indicated that 279 MPs – 85 per cent of the Eighth Parliament – failed to account for 2009/10 CDF cash.

“It had no mechanisms to control MPs from abusing it and it was little compared to other CDFs. It was unilaterally controlled by MPs. MPs would determine unilaterally. In all cases, no MP implemented because of the cost of implementation. You have Shs10 million per year then you call a constituency committee; they want allowances,” Mr Twebaze observes.

Hamstrung by these accountability and implementation problems, the CDF was ultimately scrapped in 2010.

Mr Dombo, now serving his fifth term in Parliament, was a member of the Parliamentary Commission which scrapped CDF. He says Shs10 million was too little and was unnecessarily exposing MPs.

“There was no CDF. No wonder many MPs ended up in court. If the ombudsman wanted to dig up the files of every MP, you would be surprised. Our commission took a drastic decision to abolish the so-called CDF because it could not develop any constituency,” Mr Dombo says.

Monster of indebtedness

But with the advent of the Ninth Parliament, the monster of indebtedness has reared its head again. There are new calls to revive the CDF.

Speaker Kadaga brought indebtedness at Parliament into the mainstream when she gave voice to a well-known but rarely acknowledged truth that MPs were hiding in House precincts to avoid the wrath of money lenders and debt collectors. Under current laws, an MP cannot be arrested while on the House grounds.

Pressed for cash, some MPs are either selling their political souls or shaking down the government. Early this year, Mr Oguttu dropped a bombshell with a claim that 18 Opposition MPs and an unspecified number of NRM members had pocketed between Shs110 million and Shs150 million from the government to offset their debts. That revelation has never been fully refuted.

Both Kadaga and Oguttu, as members of the Parliamentary Commission, have inside knowledge about MPs’ financial plight.

With debt saddled MPs, proposals for the re-introduction of a CDF which are likely to be tabled during the constitutional review process, could be well-received.

Mr Oguttu proposes that a Shs1 billion CDF per constituency would come in handy. An alternative proposal which he is to table in the Opposition cabinet makes the case for at least Shs30 million.

Under the envisaged model, Mr Oguttu proposes that MPs would only be limited to a supervisory role with an elected committee wielding powers to determine where to invest the money.

Mr Dombo agrees with Mr Oguttu, pointing at the Shs30 million he says he spends on repairing boreholes in his constituency during the dry season. He proposes a CDF of Shs200 million.

“There should be a committee at the village but the MP should be the last person at the approvals—to say that this is where we are going to use the money. Real spending should be determined by the committee and CAO at the district,” Mr Dombo says.

Prof Kasfir says a CDF managed by a board with members from all the sub-counties can shield the money from abuse.

“A well-constructed CDF that focuses on projects that help communities within constituencies, as opposed to individuals, would be a viable programme because MPs know their constituencies in ways that bureaucrats working for different ministries often cannot,” Prof Kasfir argues.

But there are also voices in opposition to any sort of a CDF.

Nakawa MP Ruhindi, who is also the junior Justice minister and Deputy Attorney General, argues that reintroducing a CDF would be counter-productive, noting that it would still be misunderstood by voters. He makes a case for the sensitisation of voters on MPs’ roles.

One of the MPs critical roles, according to Mr Ruhindi, is linking people to the service delivery centres and advocacy.

“It is counter-productive because the expectations of the people would be so high and that facility would not be able to manage those expectations. I would rather we insist more on government programmes and we educate our people on government programmes,” Mr Ruhindi says.

To tackle the problem of MPs facing demands from their voters, Mr Ruhindi says there must be discourse about the electoral systems, saying some people have been “toying with the idea of proportional representation”- a system where divisions in an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body.

“What they have in mind is that it would certainly help mitigate commercialisation of politics in this country. That way, you shelter the MP from unnecessary demands for services,” Mr Ruhindi says.

Members of Parliament financial woes

-Kampala Central MP Nsereko: Shs660 million.

-Gomba Woman MP Nakato Kyabangi Katusiime Shs79 million.

-Kalungu Woman MP Florence Kintu issues false cheques amounting to Shs9.9 million.

-Bungokho North MP Yahaya Gudoi spent a week in prison over a Shs20 million debt.

-Moroto Municipality MP Simon Peter Aleper dragged to court over Shs70 million.