Digital agenda: Questions linger as govt gets lost between policy and strategy

A man holding a mobile phone. Minister of Education and Sports, Janet Museveni, has emphasized the importance of strengthening cyber security for gadgets for teaching and learning. Photo | File

What you need to know:

- The Ministry of Education statement was meant to clarify government’s position on the interventions that it has come up with on planned digitalisation of the sector, it only served to see more confusion in the public about government’s real intentions

On Monday, the Ministry of Education and Sports issued a statement in which it announced that hand-held electronic devices such as mobile phones and tablets “are not allowed for use by learners on school premises” pending the passing of regulations to guide their use. Dr Dennis Mugimba, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Education, however, could not say when the guidelines will come out. He simply said they would come out “at the right time”.

Confusion

If the statement was meant to clarify the government’s position on the interventions that it has come up with on the planned digitalisation of the education sector, it only served to see more confusion in the public about the government’s real intentions and plans. It is not difficult to understand why the confusion has arisen.

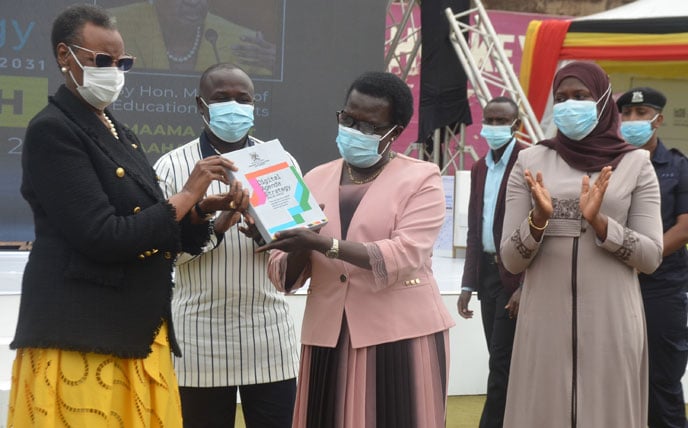

Last month, on August 23 to be precise, the Minister of Education and Sports, Ms Janet Museveni, launched the Education Digital Agenda, which not only “allowed”, but also guides on the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in schools.

The launch meant that smartphones, tablets and laptops could now be used in primary and secondary schools, albeit amid strict control by the schools’ administrations to ensure that learners are not distracted or that they do not access harmful content on pornography and gambling websites.

It should, however, be remembered that the digital agenda has taken the ministry more than four years to develop.

Dr Jane Egau Okou, the director for Higher, Technical, Vocational Education and Training at the Ministry of Education, told the media as far back as December 2020 that the government was working on developing the digital agenda.

The agenda, she said, would guide the ministry on how available equipment such as mobile phones, tabs, laptops and other gadgets could support e-learning and research. She told the media at the time that work on the agenda would have been completed by the end of that year, with implementation coming in 2021.

Ill preparation?

If what Ms Egau-Okou told the media as far back as December 2020 is anything to go by, the agenda was meant to guide the ministry on the use of those gadgets. Why then is the ministry talking of lacking guidelines more than three years after it first revealed that the agenda and what it aimed to attain were in the offing?

Besides, the need for expediting the formulation of regulations to guide the use of gadgets has been clear for a while now. The perennial lack of textbooks occasioned by either a lack of resources or changes to the curriculums has also served to bring that need to the fore.

Early in March 2022, the National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC) appealed to the government to allow students in lower secondary schools to use smartphones in schools to cover up for delayed delivery of textbooks that would help with teaching the new lower secondary school’s curriculum. Implementation of the new curriculum commenced in 2020.

"All schools have been teaching on Zoom, online and students have been having these phones throughout the holiday and have been using them as tools of learning. So I don't see the reason why now they have come back to school we stop them. And even if all these textbooks are all in schools, they are not enough,” said Mr John Okumu, the manager of Secondary Schools Department at NCDC.

It should at the same time be remembered that Uganda has for long been short of textbooks at all levels and under all curriculums. Figures from NCDC show that the textbook-to-student ratio for compulsory subjects taught in Uganda is 1:194.

Dr Mary Goretti Nakabugo, the executive director of Uwezo Uganda, the local chapter of a regional citizen-driven initiative to improve numeracy and literacy among school-age children in East Africa, says the back and forth point to a possible lack of preparedness.

“They (ministry) may have rushed to unveil (the agenda) before putting regulations and guidelines and so on in place. That is why they are backtracking,” she says.

Sections of the teaching community have been quick to accuse the government of lack of clarity on the digital agenda, though Dr Mugimba says the accusation is unfounded.

“It is not a lack of clarity. It is just a process. The digital agenda is not a policy. It is a strategy which is simply pointing in a direction. It is not the direction itself. So it is not like we are unclear or unready. That is how the process is,” Dr Mugimba argues.

Cart before the horse

However, Mr Joseph Ssewungu, the Shadow minister for Education and Sports believes that this is yet another example of haphazard planning that has often led the government to putting the cart before the horse.

“The challenge we have with Mr Museveni’s failed State is that they think of bringing policies after they have begun on something. They, for example, closed all teacher training colleges in Uganda and have declared that they want all primary school teachers to hold bachelor’s degrees, but they have never come up with course units to be taught to those teachers,” argues the Kalungu West (NUP) legislator.

Mr Ssewungu insists that it would have been incumbent for the government to first introduce a policy and also prepare other stakeholders before unveiling the agenda.

“First bring the policy, induct people into that system then open up. When we were trained in college that is how we were prepared. But these ones just come up with something with excitement,” Mr Ssewungu says.

Dr Mugimba, however, defends the government’s approach on grounds that the digital agenda is only a strategy, which did not necessitate the introduction of policies at this point.

“The digital agenda is a strategy. It is just like you can have a National Development Plan (NDP). The NDP has ambitions for the country. Now the various ambitions are unpacked in several policies. You do not wait for all the policies to be developed before you develop the NDP,” he argues.

Dr Mugimba adds that the strategy is simply a planning tool to guide the several interventions that need to be put in place.

“It is the one to guide what we need to put in place including the policy guidelines, the standards, describing the various roles of the several stakeholders to be mapped, the financing requirements etc. It is the strategy that informs that direction,” he says.

Policy or strategy?

The biggest question now is what comes first. Is it the policy or the strategy?

However, a senior management consultant, who preferred not to be named as he has several running contracts with the Ministry of Education and Sports, pokes holes in Dr Mugimba’s explanation.

Policies, he says, are indicators of an organisation’s commitment to particular goals by way of outlining its objectives. Strategy on the other hand are the series of planned actions through which objectives are realised. In other words, he adds, it is policies that guide strategy and not the other way around.

“Strategies are plans of action that are designed to enable an organisation to realise its goals and objectives. But it is the organisation’s policies that guide strategy. The strategies are meant to help realise policy objectives and outcomes,” the consultant says.

He adds that strategies outline how prior agreed policies are implemented. In other words, once a policy has been agreed upon, strategies are agreed upon or adopted formally, and a strategy outlines how that policy is implemented.

So is the government caught in no man’s land along the common borders between policy and strategy? That is for it to explain.

Necessity

While the Ministry of Education honchos are yet to grapple with finding out whether the digital agenda is a policy or a strategy, different stakeholders in the education sector say the need for digitalisation of the education sector cannot be underestimated.

“Technology has completely become part of our lives, education included, and I can see the need and urgency for the government to also ensure that our children are not left behind. If we have previously talked about people being excluded because they cannot read and write, we are headed for times when many people are going to be excluded because they cannot use technology. Our education system, therefore, has to move towards that,” Dr Nakabugo says.

Whereas the need for implementation of the digital agenda is not lost to the public, it appears that the government has mountains to climb before it achieves what it has set out to do.

Manpower challenges

Mr Ssewungu, says the biggest problem that it will have to deal with is perhaps that of manpower. He argues that most of the teaching staff who are the fulcrum of the agenda are ill-equipped to carry the agenda forward.

“Have you trained teachers to train children on how to use those gadgets? Do you know that we have teachers in Uganda who have never seen a smartphone?” the legislator asks.

It should be remembered that a 2022 e-readiness assessment found that up to 65 percent of primary and secondary school teachers in Uganda were not comfortable with integrating technology into their teaching practices. They were more comfortable with traditional approaches to teaching.

High cost of data

Mr Ssewungu blames that on mostly poverty, lack of access to the internet and the high cost of data and connectivity.

“You might give some of these teachers the smartphones, but they will be of little use to them because they cannot afford the data. It is only when they get a few shillings that they load some data and the times they do so are far in between,” Mr Ssewungu says.

Matters are not helped by the fact that Uganda has one of the highest costs of data in the world. The website www.africa.businessinsider.com reported in November 2022 that Uganda was ranked 116 out of 117 countries where the cost of data was so high. In number 117 was the Ivory Coast.

In 2020 Ugandans were also discovered to be paying some of the highest amounts for data in the East African region. They were paying an average of Shs17,231 for 1GB of data, coming second to Tanzania where 1GB cost Shs21,787 at the time.

Taxation was at the time considered to be a major driving factor. After scrapping the over-the-top (OTT) tax of Shs200 per day for the use of 50 platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, the government imposed a 12 percent tax on the net cost of Internet data and an additional 18 percent value-added tax (VAT).

Other challenges

Most important, however, are other structural issues around the internet and electricity. Where some schools have computer and computer laboratories, most of the computers are old and loaded with obsolete software that may not support the digital agenda.

At the same time, there are hundreds of schools out there that have no electricity to power computers and other electronic gadgets that are integral to the e-learning processes and the digital agenda.

There are also questions about where the implementation of whatever regulations that they come up with will begin.

“Are you stopping all schools? Or are you going to leave those in the private schools who have been using the gadgets to continue using them as you work to ensure that children in those poorer schools are gradually helped to have that uptake of technology?” wonders Dr Nakabugo.

There are also questions about who will provide the gadgets. Is it the parents or the government?

“Will a government that gives a capitation grant of around Shs15,000 per child per year under the Universal Primary Education (UPE) be able to buy the gadgets? Or is it going to leave that to the parents?” wonders Mr Ssewungu.

Would the government be able to overcome those challenges if it manages to find its way out of the no man’s land between policy and strategy?

Dr Mugimba is hopeful that the government will be able to address all those challenges by involving other stakeholders.

“As we said on Monday, the strategy is a rallying document. It is a mobilisation tool. That is why we consulted more than 30 stakeholders in its development. When you have a strategy you are simply telling your stakeholders that this is where you want to go and this is how you can put in your input. So NITA-U has to come in with the Ministry of ICT, Ministry of Energy etc. Everyone sees how to chip in to help us arrive in the direction that we want,” Dr Mugimba says.

The question is whether they will actually chip in and with what resources.