Prime

Govt failure to enforce fees rules leaves parents stuck

Dr Joyce Moriku Kaducu, the junior Education and Sports Minister. Photo | File

What you need to know:

- Despite efforts to address the issue, including guidelines issued in 2018, inadequate enforcement mechanisms persist, prompting concerns about access to education and the need for regulatory action.

Parents, who had hoped for government intervention, are on their own for now after it emerged that the Education Ministry has failed to implement guidelines to arrest exorbitant school fees.

Dr Joyce Moriku Kaducu, the junior Education and Sports minister, was at a loss of words on Wednesday after legislators pressed her to name schools that have been sanctioned for high charges contrary to the guidelines.

The government in 2018 circulated guidelines that public and private schools have to follow when setting school fees. While the guidelines do not put a cap on what schools can charge, they bar unauthorised increments, and limit school requirements that are known to escalate charges. They also prohibit cash and non-cash requirements outside the approved school fees structure.

Dr Kaducu attributed failure to implement the aforesaid guidelines to gaps in the law.

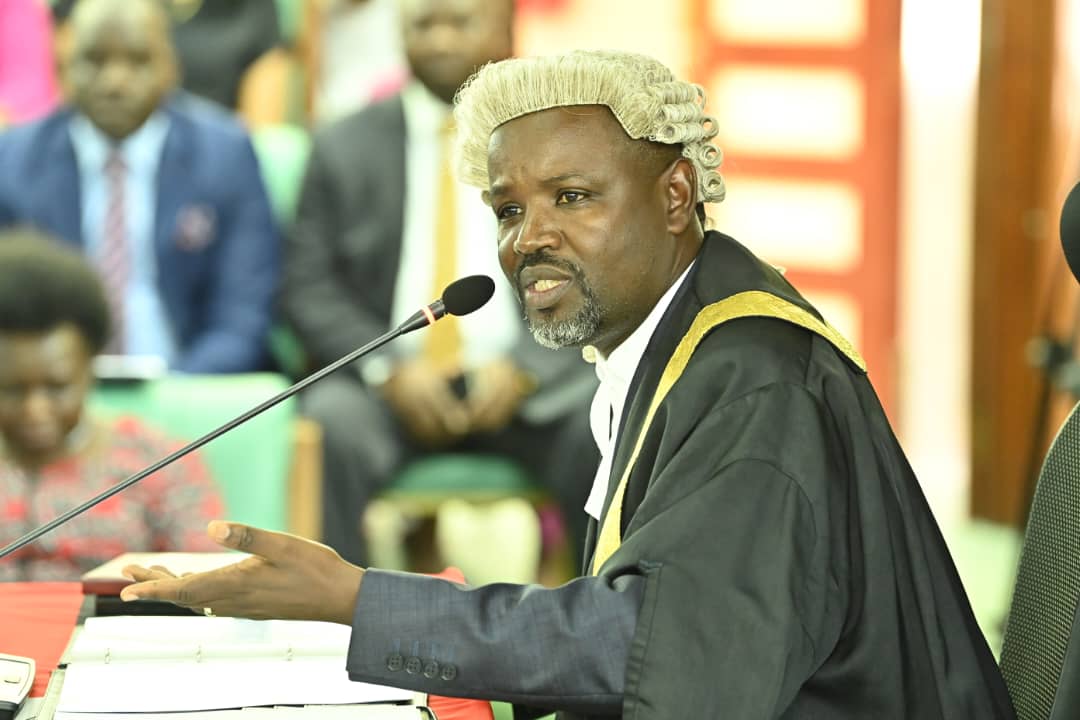

“The issue raised is about whether we are able to pass sanctions or not […] the law has […] some gaps in terms of statutory instruments and regulatory frameworks,” she said, leaving Deputy Speaker Thomas Tayebwa rather bewildered.

He said: “You put in place all these measures […] we know there are schools not adhering to them. What punitive measures are in place or there are no sanctions. Government issues guidelines, guidelines are violated. Are such guidelines issued with no sanctions.”

Deputy Attorney General Jackson Kafuuzi asked for more time to fully understand the laws before giving further guidelines.

‘Education for all’

Uganda, which runs a liberalised economy, also has a law—the Education (Pre-Primary, Primary and Post-Primary) Act, 2008—that empowers the minister to, by statutory instrument, regulate fees payable at any school. The regulations, however, only address government-aided schools.

Dr Kaducu said the guidelines took into consideration “the liberalised nature of the economy and the consequent need for [the] government to regulate rather than control levels of fees by designing guidelines, which schools must abide by.”

She further revealed that the Cabinet stood over the regulations “in a quest to fulfil the pledge of free education for all.”

“When the Ministry of Education took the framework paper for regulating such that we eventually get the statutory instrument, [the] Cabinet advised the Ministry of Education to come up with a comprehensive paper that will put in place the compulsory universal education,” she said.

“That goes along with an increase in funding of Shs309b and that will cater to the additional funds which schools are charging in recruitment of teachers, adding capitation grants and other school charges? Once that is in place, hopefully in the coming financial year, we should be in position to cut down these issues on school fees charged,” she added.

Regulation is key

Ms Janet Museveni, the Education and Sports minister, while releasing the 2023 UCE results said her docket would hold a meeting with government-aided schools that are charging high dues.

“The reason why as a government we are focusing on free and compulsory UPE and USE is to give an affordable option to our people who cannot afford the fees and charges in the private schools,” she said.

The guidelines issued in 2018 came following a litany of complaints from parents and a section of education activists that the high fees charges in both private and government-aided schools deny some students access to education, which is a right.

Ms Pheona Nabasa Wall, the former president of the Uganda Law Society, said even in liberalised economies, while the government may not set a specific price, regulation is key to ensure equitable distribution of social services and curb excesses. She, however, advised that government considers the underlying costs.

“When you have a public entity like [the] government that has liberalised the provision of essential service, they create regulators to ensure opportunistic entrepreneurs do not take advantage, and create antitrust practices, monopolies, unquestionable contracts, and do not exploit the community and protect the community rung,” she said.

Ms Nabasa added: “We know the average earnings of a Ugandan, we also know that public schools are limited. Even UPE schools are demanding inputs […] there are certain demands which need to be regulated. It doesn’t mean that the school fees have to be the same, but equitable. There will be different levels to accommodate everybody. At the end of the day, we want to see that if children from different areas sat Uneb, we get the same quality of standard on average.”

Impediments

Mr Peter Walubiri, a constitutional lawyer, questioned whether the law on regulation was well thought-out.

“The law that allowed the minister to regulate school fees is not well thought out given that the government has abdicated its responsibility to provide education services and left it to the private sector,” he said.

He added: “For you to regulate how much fees I charge students, especially for private school when you have not regulated the cost at which I buy food, building materials, the salaries I pay, the utilities, doesn’t add up. [The] government should build schools and set realistic rates for its schools.”

Mr Filbert Baguma, the general secretary of Uganda National Teachers’ Union (Unatu), attributed the failure to implement the guidelines to conflict of interest.

“Some of the policymakers and the policy implementers own schools and, therefore, in that kind of situation, it becomes difficult to implement some of the directives that come from the minister,” he said.

He contended that the minimal investment made by the government in the education sector directly impacts the quality of education provided, prompting parents to seek alternatives in pursuit of higher quality.

“Where you find the government paying Shs20,000 per year per child in a UPE school, it cannot tell a private school to charge the same amount of money because it is not enough to facilitate the teaching and learning process per child per year, which remains a puzzle,” he added.