Prime

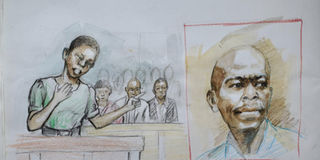

Court reduces Nyangasi sentence

What you need to know:

- Nyangasi denied having a scuffle in the toilet with his wife Christine; in fact he denied ever being in the toilet when his wife collapsed and subsequently died

The Court of Appeal delivered its judgment in the case of Nyangasi Dalton Apollo versus Uganda, filed in 2012, on November 30, 2015. One of the issues court ruled on was whether the trial judge erred in law and fact when she disregarded Nyangasi’s defence of alibi.

An alibi

Nyangasi denied having a scuffle in the toilet with his wife Christine; in fact he denied ever being in the toilet when his wife collapsed and subsequently died. In his defence Nyangasi maintained that he was in the drug shop on the outer side of the courtyard trying to catch an early customer.

The law is that an accused person who raises an alibi does not have the burden of proving it. The Supreme Court has provided guidance on the mode of evaluation in a case where an accused person raises an alibi. The rule is that where the prosecution adduces evidence showing that the accused person was at the scene of crime, and the defence not only denies it, but adduces evidence showing that the accused person was elsewhere at the material time, it is incumbent on the court to evaluate both versions judicially and give reasons why one and not the other version is accepted.

Defining crime scene

The Court of Appeal defined a crime scene as a location where a crime took place, which comprises the area from where most of the physical evidence is retrieved by law enforcement personnel, crime scene investigators or in rare circumstances, forensic scientists. The court also ruled that any other location where evidence of the crime can be found may also be considered a crime scene. In this case, to court, the toilet or bathroom, for that matter, and its vicinity were the scene of crime.

Evidence

Court considered the evidence of one of the witness at the scene of crime. The witness, in her evidence in the initial trial stated “I heard a bad noise which eventually faded coming from the latrine. I rushed to where the noise was coming from. I found Christine lying down and Nyangasi was strangling her. Christine was struggling to free her neck from Nyangasi’s hands. She was using her hands. I went towards Christine but she could not talk. Nyangasi then rushed out and went away. Nyangasi saw me before he rushed away. When he left, I tried to hold Christine and also talk to her but she could not speak.”

Corroboration of evidence

Another witness corroborated this evidence; the witness stated that when Christine moved out to go to the toilet, Nyangasi followed her and all of a sudden she heard a scream. On her way to the toilet, to the source of the noise, she bypassed Nyangasi who was moving at a terrible speed.

When the witness reached the bathroom, she found Christine down on the floor of the corridor between the toilet and the wall fence with her eyes wide open.

When the witness confronted Nyangasi and asked him what he had done to Christine, his response was “….no one messes with me and goes unpunished…..” On account of the evidence of these two witnesses, the Court of Appeal ruled that the ground raised in respect of Nyangasi’s alibi had failed.

Life in prison cancelled

The trial court did not sentence Nyangasi to death, the maximum sentence for murder. Instead the judge, in her opinion, thought Nyangasi deserved to stay away from society for the rest of his life. The judge sentenced him to life imprisonment. This led to the last 2 ground of Nyangasi’s appeal. To him the learned trial judge erred in law and fact when she meted out a sentence which was deemed to be manifestly harsh and excessive given the circumstances of the case.

In law the appellant court does not interfere with the sentence imposed by a trial court which has exercised its discretion on the sentence unless the exercise of discretion is such that it results in the sentence imposed to be manifestly excessive or so low as to amount to a miscarriage of justice.

Another ground in which the appellate court can interfere with a sentence is where a trial court ignores to consider an important matter or circumstances which ought to have been considered when passing the sentence or where the sentence is imposed on wrong principle.

The Court of Appeal considered the following when it reviewed the life sentence given to Nyangasi; for many years courts considered life imprisonment to mean imprisonment for 20 years. However the Supreme Court explained and held that life imprisonment meant imprisonment for the rest of one’s life.

Nyangasi was 47 years old when he was tried for the murder of his wife. He was trained in pharmacy in which he obtained a diploma. Between him and his wife, they had two children who had now lost parental guidance and love of both parents.

There was no previous criminal record disclosed against Nyangasi during sentencing. The trial court also found that the commission of the crime had been motivated by a series of family and domestic misunderstandings.

And at the time of sentence, Nyangasi had been on remand for about two years.

Considering all the circumstances of the case, the Court of Appeal found that the sentence given to Nyangasi to serve was harsh and severe. Court was persuaded by the mitigating circumstances submitted by Nyangasi’s lawyer and reduced his sentence from life imprisonment to imprisonment for 25 years to run from the date he was sentenced by the High Court. Nyangasi was, however, still dissatisfied by the decision of the Court of Appeal. He appealed to the Supreme Court, the court of final appeal in the country.

To be continued