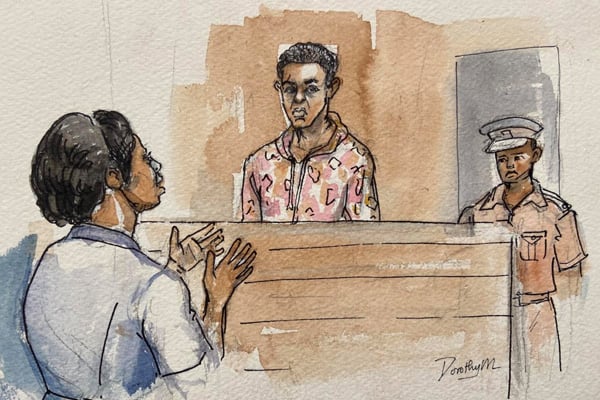

Abdulahi Mohamed, a young man of Somali origin, was arrested and charged with murder of a fellow country man, Abdaifatah, who was stabbed in the chest on the streets of Nairobi. Abdulahi was positively identified, to the court’s satisfaction, by two eyewitnesses of the incidence, as the person who stabbed Abdaifatah.

An issue that court had to determine was whether the element of malice aforethought was proved by the prosecution to the required standard. Malice aforethought is said to be proved where the evidence adduced establishes that there was intent to commit a serious offence and that in the execution of that offence death was caused. Court was satisfied that the evidence adduced proved that the accused and his accomplishes were in the process of committing a robbery, and that in the execution of the robbery the deceased was stabbed in the chest when he intervened in an attempt to prevent the robbery.

There were however other legal challenges during the trial; the murder weapon was never recovered. The issue here was whether that was fatal to the prosecution case. The investigation officer testified that he took over the case two months after the incident. By that time the accused was already in police custody. The officer told court that he visited the house of the accused and that he did not recover any weapons. There was no evidence of who arrested the accused or when he was arrested. There was no information to indicate whether the arresting officer tried to recover the murder weapon. To court it is desirable that a murder weapon is recovered. In this case, to court, the prosecution failed to adduce evidence of arrest in order for court to draw a conclusion whether effort to recover the weapon should have reasonably been made. That notwithstanding, court found that given the circumstances of the case, the lack of a murder weapon did not substantially affect the prosecution case.

The defence in this case also contended that the prosecution failed to call crucial witnesses. In criminal cases, the maxim is that the prosecution makes available all witnesses necessary to establish the truth even if their evidence may be inconsistent. And where the evidence called is barely adequate, the court may infer that the evidence of witnesses not called would have been adverse to the prosecution.

Prosecution did not call some crucial witnesses to testify and among these was the victim of the robbery. To court the victim ought to have been called to testify as a witness. From the other evidence it was clear that the victim was known by the deceased and that the victim was the one who called to the deceased to assist him from being robbed. The eyewitnesses, who were with the deceased, did not know the victim of the robbery. To court the victim should have shown interest to follow up with the police the death of his helper and give his statement. He appears to have gone underground. Court therefore found it difficult to draw an adverse inference against the prosecution for the failure to avail this witness.

The other crucial witness was the initial investigating officer in the case. His evidence was glaringly missing. To court his evidence was crucial. He ought to have spoken about the investigations he carried out and how, where and when he arrested the accused. However, to court failure to call this witness did not weaken the prosecution case since the officer who took over the case completed the investigations and charged the accused and gave evidence in court. To court even though the initial investigating officer was not called as a witness, this did not occasion the defence to suffer any prejudice. The evidence adduced by the second investigator was sufficient to establish the truth in this case.

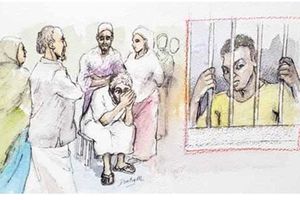

Court noted that it look long to deliver judgment in this case but this was because an application was filed by the defence seeking to be allowed to enter into plea bargaining. This was after the entire case was heard, submissions made and a judgment date set for the case. The court stayed the judgment and allowed the defence to argue the application. The defence told court that notwithstanding the pending judgment, the two parties were negotiating and seeking an out of court settlement in accordance with the Somali culture, law and religion. It was also the wish of the complainants to settle the matter out of court as they had already signed an agreement and reconciled and felt that the agreement ensured justice for them and the community. The accused, an orphan, had been in custody for three years and the defence told court that he had learnt his lesson and was remorseful for the offence and if given time, there were high chances he would change his life and move in a different direction.

The prosecution however, opposed the application as it was not involved in the process, and argued that it was clear in law on how murder cases should be handled and it was for that reason that the case was before court. To the prosecution all criminal cases are instituted and prosecuted in the name of the state and not that of the family and court, therefore, needed to proceed with the case to its logical conclusion. And bypassing the prosecution in any plea bargaining would be departing from the essence of public prosecutions.

The court agreed with the prosecution and considered that the case against the accused, a case of murder, was a very serious offence and, as such, reconciliation as a form of settling the proceedings was wrong and prohibited. To court the request for reconciliation was made late when the case had been heard to its conclusion. The application was henceforth dismissed and disallowed and court pronounced itself on the case.

Court, having considered the entire evidence adduced by the prosecution was satisfied that there was no dispute that the accused was at the scene at the time of the incident. Court was satisfied that the accused is the person who stabbed the deceased and that he stabbed the deceased with the clear intention of preventing the deceased from helping someone who was in the process of being robbed of a mobile phone. The deceased was stabbed to aid the accomplices of the accused complete the robbery.

Court was also satisfied that the prosecution had established beyond reasonable doubt the ingredient of malice aforethought; that at the time the accused stabbed the deceased, he had formed the intention to either cause death or grievous harm to him. Court rejected the defence of the accused and found him guilty of the offence of murder.