Prime

12 ways to make healthcare cheaper

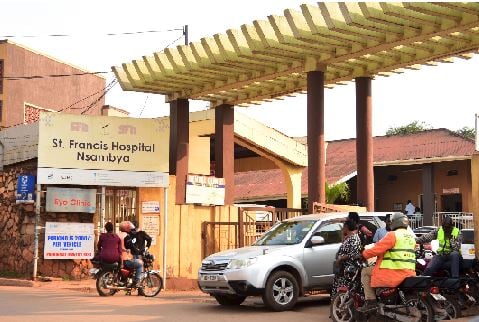

St Francis Hospital Nsambya in Kampala is one of the most sought-after hospitals in the country. Stakeholders are negotiating fair costs of healthcare service delivery in both private and government hospitals. PHOTO | FRANK BAGUMA

What you need to know:

- There are concerns that include inadequate standardisation and regulation of charges, leading to discussions and legal actions aimed at addressing these issues.

The January 16 High Court’s landmark decision has sparked renewed discussions on the feasibility of lowering and regulating the prices of medical services, particularly in private facilities, which many people characterise as exorbitant.

In his ruling, Justice Phillip Odoki directed that the government should, within two years, ensure there is necessary legislation to regulate and standardise levies, rates and pricing of medical services provided by private health facilities to ensure access and affordability.

He warned that if the trend of high charges is unchecked, the “violation of the right to health” of the citizens will continue.

However, the leadership of the Uganda Healthcare Federation (UHF), the umbrella body for players in the private health sector, said regulating the charges is complex and requires a clear understanding of cost drivers.

“…this is an open economy and we live in a landlocked country with hardly any health inputs produced locally,” Ms Grace Ssali Kiwanuka, the UHF executive director, told this publication on Tuesday.

“This said, we are at the mercy of currency fluctuations and levies applied to health inputs from the country of origin to the service point.

“So, if we set aside that to have government regulate prices in health then they will have to not only regulate health but multiple sectors that affect the cost of health service delivery, which includes cost of water, electricity, fuel to run generators and travel to pick and drop inputs, for example, oxygen, medicines among others,” she added.

International Hospital Kampala is also a popular facility. The private sector argues that regulating charges is complex due to multiple factors affecting the cost of health service delivery. PHOTO | FRANK BAGUMA

The discussion about charges in private facilities is important because the establishments constitute more than 40 percent of the health service providers in Uganda, according to government statistics.

Dr Herbert Luswata, the president of the Uganda Medical Association , expressed skepticism about the proposal to regulate medical charges.

“Ministry of Health cannot control prices in the health sector. Has the government controlled bills in law firms, school fees, among others? Doctors in the private sector will not comply,” Dr Luswata said in a brief comment.

The landmark ruling by Justice Odoki followed an application by the Health Equity and Policy Initiative to the High Court, petitioning Health minister Jane Ruth Aceng and the Attorney General, for government’s failure to standardise levies, rates, and pricing of medical services provided by private health facilities.

“The Minister of Health is to ensure that all essential stakeholders are consulted on fair and affordable payment ceilings for all medical treatments provided by private health facilities,” Justice Odoki ordered.

Asked about their next step as the Health ministry, Dr Tom Aliti, the commissioner for partnerships and multi-sectoral coordination, told this publication in a brief comment: “It’s Parliament to regulate.”

Ms Kiwanuka said private health providers struggling to remain operational, which is a huge risk for this country if the private health sector starts to shrink.

“As the Federation, it is at the heart of what we do to explain how the private health sector operates because it is often misunderstood that they only want profits which is incorrect,” she said.

“Fact is, a number of private providers are struggling to break even. The number of private facilities that has closed, is on sale or has been sold over the last 10 years has multiplied at an increasing rate because health care is just not a profitable business,” she added. She, however, did not provide the figures.

Background

This is not the first time the court has ruled about the cost of care in private facilities.

During the peak of Covid-19 pandemic in 2021, the High Court in Kampala also ruled that “the Health minister, Dr Jane Ruth Aceng, and the Attorney General must make regulations for reasonable fees payable to hospitals for management and treatment of Covid-19 patients.”

This followed a case that was filed by Center for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD) and Mr Moses Mulumba, the executive director of Civil Society Organisation, seeking intervention over high medical bills.

By then, many private hospitals in Kampala were charging between Shs2 million and Shs5 million per day to treat a critically ill Covid-19 patient in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and medical bills for the entire treatment duration would go past Shs100 million in some facilities. Many people said they took their patients to private facilities because public facilities were full but some also believe quality of care is higher in private facilities.

Ms Robinah Kaitiritimba, the executive director of Uganda National Health Consumers’ Organisation (UNHCO), said because of the high charges, communities were “being driven into poverty and others were being asked by hospitals to bring land titles.”

“We need a regulation that protects consumers; not just for Covid-19 but for all forms of medical care,” she said.

However, Dr Aceng while appearing before Members of Parliament in July 2021, said what the government was spending on each Covid-19 patient was similar to what private facilities were charging.

“We engaged a consultant to calculate for us the cost of managing a patient in our ICU in Mulago [Hospital]. Incidentally, the costs are not different from that of the private sector. Every patient in the ICU takes about Shs3 million per day in Mulago and those in the High Dependency Unit (HDU) take Shs788,516 per day,” Dr Aceng said then.

That same year, Dr Timothy Musila, the assistant Commissioner for Private Sector Coordination at the ministry, said the ministry was waiting for the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) to negotiate and better regulate the cost of care in the country. The NHIS Bill is yet to be tabled by the government before Parliament for approval.

Hope

However, there remains optimism about implementing price ceilings. Ms Kiwanuka of UHF mentioned ongoing discussions with the government on effective ways to regulate charges. She said the Federation has been advocating for pooled purchasing of health supplies to bring prices down.

“We have been advocating for affordable health financing that’s why we have started supporting private facilities to access equipment and instruments using payment plans so that we ease the pressure on the facilities to pass the high cost of borrowing to access these items.

“The way forward would be to support private providers with solutions to the increasing cost of service delivery. Bring in cost saving initiatives such as strategic purchasing of services by government so that you have a predictable agreed cost of care and if you even provide the inputs you have latitude to set prices not through legislation but through a contract.

“To guide this, we can quantify the cost of service delivery in government facilities to give a baseline and then add the costs incurred by private providers that are not faced by the government,” Ms Kiwanuka added.

There have also been complaints that even Private Not-for-Profit (PNFP) facilities are charging their clients.

Dr Tonny Tumwesigye, the executive director of Uganda Protestant Medical Bureau (UPMB), which controls a chain of PNFP facilities, said they are also engaging the government on controlling the costs.

“Health service delivery is very expensive. There are a lot of old infrastructure and the only way they can get money is through charging fees. One of the things we have been discussing is how we can approach government to increase primary healthcare conditional grant so that we can offset a number of these costs,” Dr Tumwesigye said.

“Of course, these [PNFP] hospitals don’t necessarily charge as the private facilities. Also, there is no dividend, we don’t save money and share. All the money that is generated is reinvested back into hospital operations. If you look at the audited financial accounts of these [PNFP] hospitals, they are actually making losses,” he added.

This reporter couldn’t independently verify this.

The UPMB boss also said the recent salary enhancement for health workers in the public sector has increased pressure on their system. “Infrastructure and human resources are the main drivers because you must have these consultants paid salaries. You know government has increased salaries of health workers in the government facilities,” he said.

A health worker attends to a patient at Mulago hospital in 2021. Photo | File

“And as a result, many of our workers are leaving and so we are faced with a dilemma of trying to keep staff who are already serving and are good. Donors that used to give us resources are no longer there. Most of them are tired,” he added.

He noted that not everyone is supposed to go through the private wing in their PNFP facilities.

“We also have the Samaritan arm. While we try to put up the private section, we also have this arm that caters for those who cannot afford it,” he said.

Sufferings in public facilities

The issues around high medical expenses are not limited to private and PNFP facilities, patients and their families are also experiencing catastrophic expenses in public facilities, according to research reports.

A 2017 study report by Geoffrey Anderson and colleagues, indicated that although it is “Ugandan governmental policy that all surgical care delivered at government hospitals in Uganda is to be provided to patients free of charge,” frequent stock-outs and broken equipment require patients to pay for large portions of their care out of their pocket.

The researchers said they interviewed 295 out of a possible 320 patients in a “large regional referral hospital in rural southwestern Uganda” during the study period -in 2016. They indicated that 46 percent of the patients met the World Bank’s definition of extreme poverty ($1.90/person/day).

“After receiving surgical care an additional 10 patients faced extreme poverty, and five patients were newly impoverished by the World Bank’s definition ($3.10/person/day). Thirty-one percent of patients faced a catastrophic expenditure of more than 10 percent of their estimated total yearly expenses.

“Fifty-three percent of the households in our study had to borrow money to pay for care, 21 percent had to sell possessions, and 17 percent lost a job as a result of the patient’s hospitalization. Only five percent of our patients received some form of charity,” the report reads.