European Union delegates in Kampala in 2022. Activities of DGF are financed by Denmark, Ireland, Austria, UK, Sweden, Norway, and the EU. PHOTO | FILE

During the high-octane 2020 campaigns ahead of the January 14, 2021 poll, the Democratic Governance Facility (DGF) provided a grant worth Shs1 billion to New Vision Publications Limited to undertake investigative journalism stories that require a deeper inquiry to unearth wrong-doing.

A climate of suspicion and fear had already engulfed the partly government-owned legacy media house when the funding was dispatched. Robert Kabushenga, whose termination as the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) had earlier been reversed by the Chief of Defence, Gen Kainerugaba Muhoozi in 2018, was already a marked man. His fate was sealed when a grossly embellished intelligence dossier claimed that he had accepted funds from the basket fund supported by eight European Union (EU) countries meant to ostensibly sway the election of the National Unity Platform (NUP) party’s Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu alias Bobi Wine—a youthful candidate whose red beret revolution swept out the ruling party across its central region stronghold.

After two years of suspension, on June 22, 2022, the President agreed to lift the ban on the condition that the Government of Uganda (GoU) was represented in the DGF’s decision-making structures. The donors, however, declined the offer, and, in October, the Fund was closed.

The Fund, which had adopted a de-politicised approach by providing funding to both state and non-state actors, led to the shutdown of critical programmes that directly uplifted the underclass and provided employment to thousands.

Disinformation

The authors of the dossier upon which Mr Museveni acted, according to sources, elected not to reveal that the DGF financial assistance also funded vital government agencies like the National Environmental Management Authority (Nema) the Justice Law and Order Sector (JLOS), and the Law Development Centre (LDC), among others. In a country with an acute need for legal aid for poor persons, the exit of the DGF facility left a gaping hole in the provision of these legal services.

In 2021, Aaron Besigye, the national coordinator of Justice Centres Uganda (JCU), ominously warned that 7,600 cases in various courts could stall due to the closure. Many of these cases were related to land evictions, domestic violence, administration of estates, and human rights abuses.

“The closure of DGF means that 7,600 cases that are registered in the court system, where we had instructions and representing them as their lawyers, are to be affected. Failure to get alternative funding means it’s the greatest injustice you are going to create, especially for the poor since the rich always get through with what they want at the expense of the poor,” said Mr Besigye.

JCU is a government project of JLOS that was rolled out in December 2009 as part of the legal aid clinic seeking to expand the frontiers of justice at the grassroots. DGF was previously running a three-year project to enhance access to justice in Uganda through providing comprehensive legal aid services and empowering vulnerable people and communities.

With 80 percent of its funding supported by DGF to the tune of Shs40 billion, Mr Besigye revealed that 13 legal aid service centres “could shut down and 73 lawyers could lose their jobs.”

Deportations

The exit of DGF, which contributed billions of shillings in taxes, had a significant economic impact on Uganda’s limping economy—attempting to shake off the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Barely a month after the election results were announced, Finance Minister Matia Kasaija, who was acting on the orders of the President, on February 17, 2021, ordered the suspension of the DGF facility. The president accused DGF of harbouring an imperialistic agenda by financing “activities and organisations designed to subvert government under the guise of improving governance.”

After two years of suspension, on June 22, 2022, the president agreed to lift the ban on the condition that the government of Uganda (GoU) was represented in the DGF’s decision-making structures. The donors, however, declined the offer, and, in October, the Fund was closed.

The Fund, which had adopted a de-politicised approach by providing funding to both state and non-state actors, led to the shutdown of critical programmes that directly uplifted the underclass and provided employment to thousands.

Disinformation

The authors of the dossier upon which Mr Museveni acted, according to sources, elected not to reveal that the DGF financial assistance also funded vital government agencies like the National Environmental Management Authority (Nema) the Justice Law and Order Sector (JLOS), and the Law Development Center (LDC), amongst others. In a country with an acute need for legal aid for poor persons, the exit of the DGF facility left a gaping hole in the provision of these legal services.

In 2021, Aaron Besigye, the National Coordinator Justice Centres Uganda (JCU), ominously warned that 7,600 cases in various courts could stall due to the closure. Most of these cases were related to land evictions, domestic violence, administration of estates, and human rights abuses.

“The closure of DGF means that 7,600 cases that are registered in the court system, where we had instructions and representing them as their lawyers, are to be affected. Failure to get alternative funding means it’s the greatest injustice you are going to create especially for the poor since the rich always get through with what they want at the expense of the poor,” said Mr Besigye.

JCU is a government project of JLOS that was rolled out in December 2009 as part of the legal aid clinic seeking to expand the frontiers of justice at the grassroots. DGF was previously running a three-year project to enhance access to justice in Uganda through providing comprehensive legal aid services and empowering vulnerable people and communities.

With 80 percent of its funding supported by DGF to the tune of Shs40 billion, Mr Besigye revealed that 13 legal aid service centres “could shut down and 73 lawyers could lose their jobs.”

Deportations

The exit of DGF, which contributed billions of shillings in taxes, had a significant economic impact on Uganda’s limping economy—attempting to shake off the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In attempting to reset the rules of engagement with Western-led non-profit organisations ahead of the general election, the government expelled high-profile EU diplomats in November of 2020. The diplomats were directly responsible for finances to enhance civic education and election-related activities. Among those deported was Simon Osborn, an influential figure in the diplomatic community who served as the advisor for the EU on elections in Uganda. Osborn was carted off by security personnel to the airport and his colleague Marco Deswart, who was the DGF head of election programmes, was told by the Dutch immigration department that he was persona non-grata shortly before he could board the plane at Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport to Entebbe at the end of his leave.

Lightning strikes twice

The authors of the recent intelligence reports, which accuse NGOs of financing street protests appear to be relying on the playbook. This debate has set off a firestorm and fed the misinformation and disinformation eco-chamber in the post-truth era where governments wage propaganda wars, elites, and corporations vie to dominate news coverage. The foreign funding accusations ignite the broader debate on accountability and transparency of the NRM government, NGOs, and the Opposition.

Agora Discourse, a non-profit organisation whose activities have exposed graft in the upper echelons of power, has recently been thrust into the crosshairs. Much of the criticism on social media platforms, including X, has largely been peppered with falsehoods such as claims that the non-profit’s leaders have used the funding to finance street protests and purchase palatial homes in Kampala.

Agather Atuhaire, the non-profit’s team leader who is a bold voice against graft, told Sunday Monitor thus: “I have said before on my Twitter [X] handle that corruption and impunity and self-seeking fight back. Agora has stepped on so many toes. And these are [the] toes of powerful people with resources to pay some desperate Ugandans to attack and try to discredit us.”

She added: “The purpose is to erode the trust and confidence the public has in Agora, but the plan has failed miserably. For others, it is a fight for the limelight. One of the individuals spreading these false accusations said we are ‘gatekeeping’ online activism […] that we have become ‘demigods’, but this is the same person who has accused us of being lazy activists who think online activism can change anything.”

‘Smoking gun’

One of the smear campaign tactics falsely labelled as the ‘smoking gun’ revealed that Agora received $200,000, the equivalent of Shs743m, from the US Agency on International Development (USAID).

“They wanted to claim that the funding Agora got from USAID was for funding protests. But we applied for this from USAID in May last year. We received it in November and it has been supporting the work we articulated in our application. The work that many Ugandans acknowledge and appreciate. How is it connected to protests that happened a year later?”

However, the funding was not a new revelation, which was already published on the Agora website. “We should be putting these people to task to produce evidence so that we avoid regurgitating baseless and damaging allegations. I have heard this. At first it was claimed that the EU gave me money to pay protestors, they eventually dropped this because they couldn’t prove it and many Ugandans saw through their propaganda. In fact, the protestors, when they were released, set the record straight that no one paid them,” Atuhaire told Monitor.

The Agora annual budget pales in comparison to the expenditure of the Inspectorate of Government, whose budget estimate for the year 2024/2025 stood at Shs90 billion. Despite efforts to torpedo its activism, Agora Discourse has spent its modest budget to outperform government-led watchdog agencies that are better funded and have the support of other government departments, including the Police and the Directorate of Public Prosecution, (DPP).

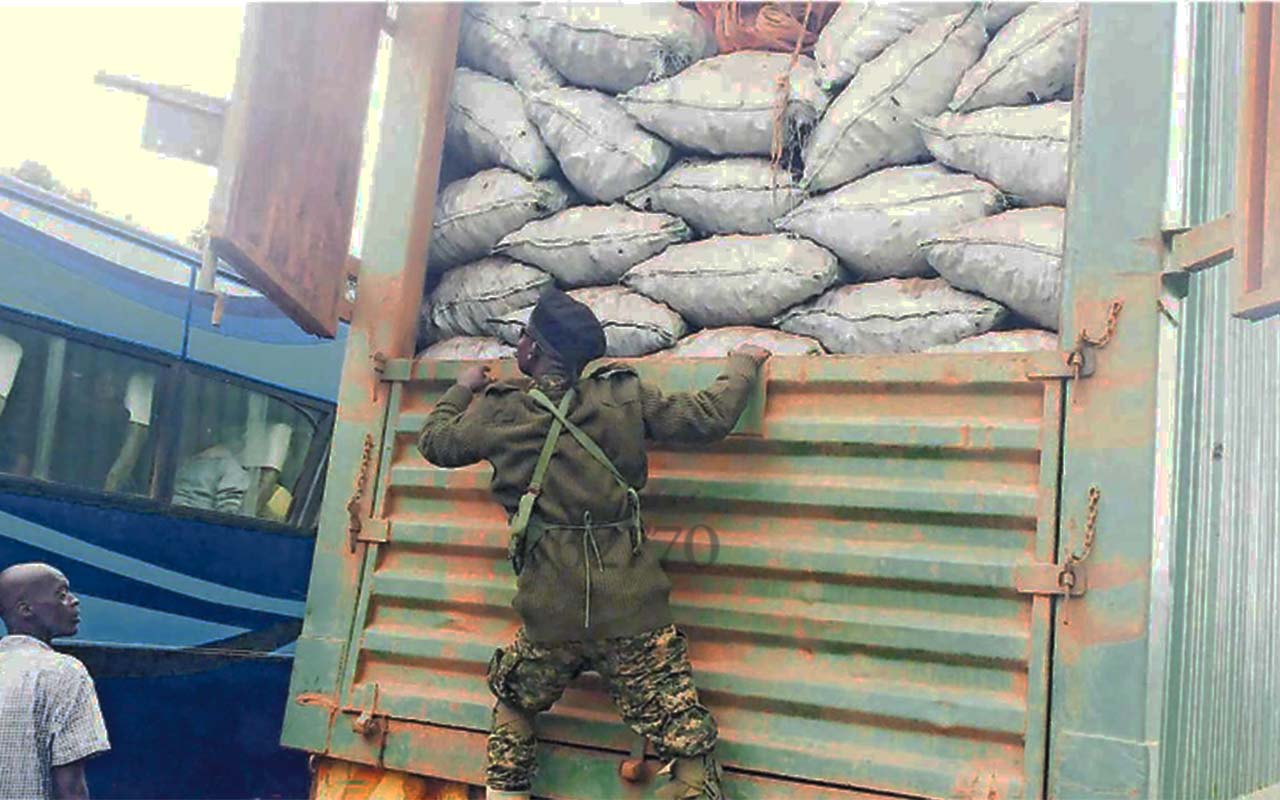

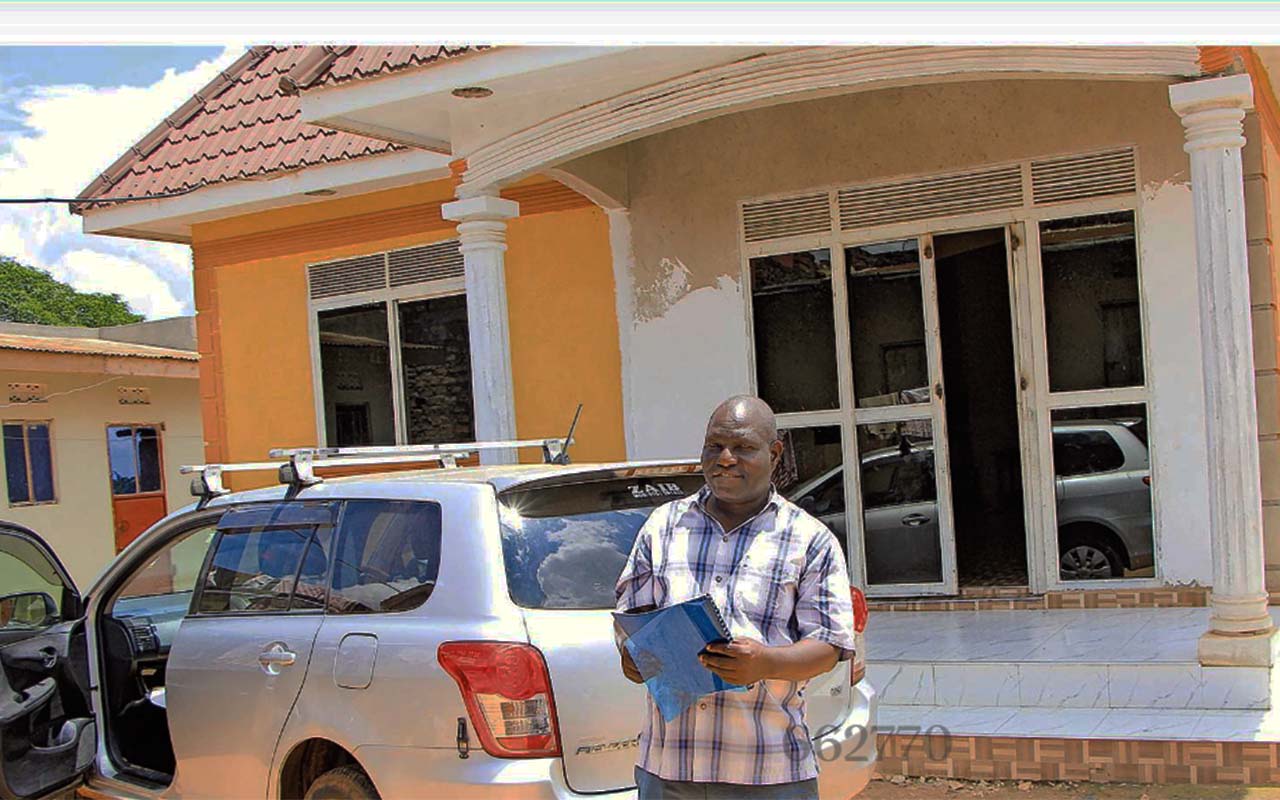

Whereas Agora’s image remains intact, to an extent, the NGO space in which it operates is not squeaky clean. Largely a mirror of society, some NGO honchos have misappropriated donor funds by forging invoices or stealing their employees’ salaries to construct houses, apartments, and shopping malls. Observers say there is a need to impose a higher threshold of accountability for Opposition parties that receive foreign funding as one who comes to equity must come with clean hands.

GoU a beneficiary

Beyond the NGO sector, foreign funding that governments receive is largely influenced by their geo-political posture. Uganda remains a major recipient of US military aid in Africa, 22 years after the deadly terror attacks at the World Trade Center in New York—an event that reshaped the East African geo-political contours.

As a result of the attack, Uganda became a major proxy of the West in the fight against terror in the Horn of Africa enclave. Mr Museveni, whose government in the late 1980s embraced neoliberal orthodoxy, was anointed the point-man of the West in the volatile Great Lakes.

According to recently de-classified data from the US State Department, from 2019 to 2021, Uganda was amongst the five highest recipients of US military aid in Africa. Uganda trailed Nigeria and Chad afflicted by the Boko-Haram insurgency and political instability; Kenya, which faces the threat of Al-Shabaab insurgents from neighbouring Somalia; and Niger convulsed by terror activities in the Sahel.

According to the author Helen Epstein, in her book entitled Another Fine Mess: America, Uganda and the War on Terror, shortly after the 9/11 attacks, Mr Museveni hired Rosa Whitaker, “a shrewd Bible-quoting African-American lobbyist and former assistant trade representative in the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations” to promote his image in Washington as an expert on the Somalia situation.

In 2003, Ms Whitaker arranged Mr Museveni’s White House visit and sent letters reminding State Department officials that Museveni was “strongly supporting the US in the global war against terrorism.” Soon presidents Bush and Museveni were speaking frequently by telephone.

$1b investments

According to the United States embassy website in Kampala “through 13 government agencies, the United States invests almost $1 billion annually in Ugandan communities to promote economic growth and employability, to improve health and education, to uphold democratic values, and to strengthen security.”

It is not only the NRM government, which has received generous funding from the West. Opposition parties, including the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), whose leadership in the past, according to highly-placed sources, enjoyed close ties with the United Kingdom’s Conservative Party during David Cameron’s reign between 2010 and 2016, was a recipient of funds from the West. Ditto the National Unity Platform (NUP), which has close ties to liberal-leaning organisations in Europe and the United States.

Is there plausible evidence to back the claims that the Opposition and non-profit organisations have received funding from the West to finance a street insurrection against the government or are these 'fabricated intelligence dossiers' part of the neo-colonial agenda tropes? For now, this remains a my-word-against-yours deadlock.