An invigilator checks students at Lakeside College Luzira before sitting for their first paper of Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) on April 12, 2021. PHOTO/FILE

The government has abandoned the new proposed A-Level curriculum it developed two years ago, only two months before the Senior Five entrants join.

Highly placed sources in the Ministry of Education said as a stop-gap measure, they are now reviewing all A-Level subjects to create an abridged curriculum for the new S5 students.

The first cohort of students under the new lower secondary curriculum completed their Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) exams last Friday and are to progress to S5 in February next year.

This meant NCDC had a two-year window from 2022 to 2024 to finalise the update of the A-Level curriculum before this group joined S5, but they failed to deliver this on time.

The sources said the government realised it lacked the time and resources to fully overhaul the A-Level curriculum, retool teachers, develop textbooks, and prepare instructional materials for the competence-based students who are set to join S5 in February next year.

Fixing the gap

The sources said the ministry has now involved subject experts in the shortcut review to ensure the new S5 entrants will use a curriculum somewhat aligned to the competence-based principles when they join A-Level next year.

To achieve this, the ministry has now invited an unspecified number of teachers to the National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC) and has started reviewing the subjects.

“The current A-Level curriculum is overloaded, and we want to make it lighter like the O-Level one. NCDC is working with various experts and subject teachers to identify and remove the outdated content,” one of the sources said.

Daily Monitor has seen an October 29 letter inviting teachers to converge at the NCDC offices in Kyambogo, Kampala City, from November 4 to 8 for the exercise. The invitation letter signed by Dr Grace Baguma, the NCDC executive director, indicated that the subject review would be done through a subject panel.

The October 29 letter said: “The Ministry of Education has committed to aligning the existing A-Level curriculum with the lower secondary curriculum to enable a smooth transition to A-Level beginning in 2025.This requires adjusting the objectives in the existing curriculum to learning outcomes, revisiting pedagogy and assessment, and removing overlap and obsolete content.”

But the sources added that the government is open to revisiting the proposed A-Level curriculum overhaul in the future to achieve a complete transition.

The current lot of Senior Four candidates, who completed their UCE exams last Friday, are the first cohort to study under the new lower secondary curriculum launched by the government in 2020. Their transition to S5 has now left the government with only December and January to review the entire A-Level curriculum—a process experts estimate would require about a year for effective implementation.

Minister speaks out

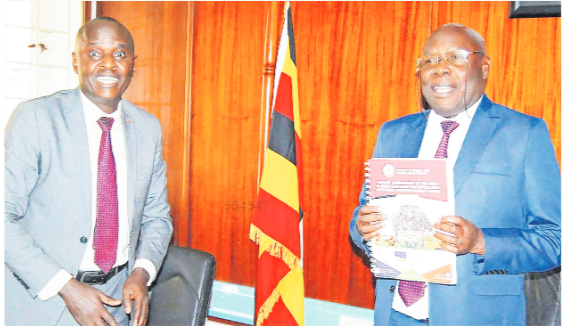

Indeed, Dr John Muyingo, the State minister for Higher Education, confirmed that the remaining time is insufficient for a full overhaul.

He said the stop-gap measure for an abridged version of the current A-Level curriculum would ensure the students have structured material when they start S5.

“We had started the review of the A-Level curriculum, but we noticed it required a lot of money and time. So we resolved that even as the full overhaul process takes place, we will come up with an abridged curriculum for the current A-Level,” Dr Muyingo said. He said the ministry was in control of the situation and urged the public not to panic.

Dr Muyingo said the abridged curriculum will contain some of the content omitted from the lower curriculum and it will also remove outdated content from A-Level.

“The public should not panic. We assure them that there will be a curriculum aligned with what our O-Level students have been studying. We arranged this to avoid subjecting them to the complete old curriculum. We might not change a lot of content for them, but it will be abridged, like we did during the Covid-19 pandemic,” he said.

Dr Muyingo said the ministry would align the teaching methodology of the abridged curriculum with the lower secondary competence-based curriculum to ensure a smooth transition for the learners. He said the abridged curriculum would only be temporary and used for the next two years as NCDC conducts a comprehensive review and overhaul to deliver a well-developed and durable A-Level curriculum for Uganda.

Aspects of suspended A-Level curriculum

The proposed new A-Level curriculum was intended to enable students to complete A’ level education over two o five years. This flexibility aimed to support students who might need additional time, accommodating diverse learning paces and reducing dropout rates.

Proposed curriculum changes included replacing the General Paper with practical “contemporary studies” to cover essential skills, such as generic skills, ICT, research techniques, financial literacy, climate awareness, and functional statistics, reflecting the need for adaptable skills in today’s workforce.

Another significant reform was the introduction of a modular assessment approach, allowing students to retake only the subjects they failed in the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) exams instead of retaking the entire exams.

School-based assessments would account for 20 percent of the final grade, similar to the assessment structure of the new lower secondary curriculum, which would help assess students’ competencies beyond standardised exams.

Subject combinations in the proposed curriculum would be more targeted, requiring students to select two essential subjects, one vocational subject, and one from contemporary studies, thus giving them a robust foundation in their chosen fields.

For instance, a student pursuing economics would study Economics and Mathematics as essential subjects, and choose a vocational subject like ICT or Nutrition, and include a contemporary studies component.

What experts say

Education experts have faulted the government for delays in the review of the A-Level curriculum. Teachers argue that the government had four years to change the A-Level curriculum, ensuring readiness by the time the pioneers of the new lower secondary curriculum join S5.

Mr Filbert Baguma, the secretary general of the Uganda National Teachers Union (Unatu),said the abridged curriculum comes too late, though it provides some relief for the anxious S4 candidates.

“These are now four years since implementing the O-Level curriculum. Why should we struggle with the A-Level curriculum, yet we knew students would finish O-Level and transition to A-Level? Why should we have a different curriculum in primary, a new one in O-Level, and an abridged version in A-Level? They are completely different,” Mr Baguma said.

He warned that if the government fails to allocate funds to train teachers on delivering the abridged curriculum, confusion similar to what occurred during the implementation of the O-Level curriculum might recur.

When the O-Level curriculum was implemented, about 40 percent of teachers were trained, but some schools continued teaching the old curriculum for one to two years due to lack of guidance.

Mr Aron Mugaiga, the Secretary General of the Professional Science Teachers Union (UPSTU), urged the government to learn from past mistakes and deliver an improved curriculum.

“There were delays in training teachers for the previous O-Level curriculum, and several teachers had to learn on the job. This time, they should prepare the teachers early enough,” Mr Mugaiga said.

However, he opposed the review of only individual subjects, rather than the entire curriculum, arguing that a complete overhaul of A-Level content would yield better results for the lower secondary curriculum.

Mr Hasadu Kirabira, the chairperson of the National Private Education Institution Association (NPEIA), said they plan to write to the Ministry of Education within two weeks after the Third Term closes, demanding that the abridged curriculum be released on time to avoid confusion.

“NCDC should have already informed the public on how things will be done. As teachers, we are ready to deliver the curriculum, but the managers seem unready. We are nearing the end of the term, yet they remain silent,” Mr Kirabira said.

He added: “We don’t only need to prepare teachers, but students and parents as well. The ministry is waiting to call us a week before schools reopen to confuse us again.

The gaps in the new lower secondary curriculum cited by the Auditor General in 2023

• Many teachers were not fully trained before the curriculum rollout, and those trained struggled with aspects like continuous assessment.

•Over half of the trained teachers reported the training as ineffective due to short durations (4-7 days) and high content volume.

• Limited frequency of sessions and lack of an ongoing training plan hindered teachers’ ability to master the curriculum.

•Textbooks and guides were delayed by two years, with initial implementation beginning without essential resources.

•Limited textbooks resulted in high student-to-textbook ratios (e.g.,1:294 in some cases), while some elective subjects had no textbooks

at all.

•Many government-aided schools lacked classrooms, desks, libraries, ICT facilities, and laboratories, making it difficult to accommodate

large numbers of students and implement the CBC effectively.

• High enrollment rates in government schools led to overcrowded classrooms, with student-desk ratios as high as 1:5 against the ideal

1:3.

• Shortage of computers, projectors, and internet-limited ICT integration, crucial for the learner-centered, research-focused CBC.

•Teachers were not trained to use ICT in lesson preparation, resulting in continued use of traditional methods.

• Schools struggled with the high cost of the internet, averaging Shs1,999,773 per term, affecting students’ research opportunities.

• Inadequate instructional materials for students with disabilities (e.g., lack of assistive devices) and unsuitable ICT equipment for visually impaired students hindered effective learning.

•Schools lacked standard verification of assessments by UNEB and used varied assessment criteria without a reliable system to relay

continuous assessment results.

• NCDC had not established a robust monitoring and evaluation system with tools and frameworks for regular data collection and reporting on curriculum implementation.