Prime

Govt to send protest note to Kenya over maize ban

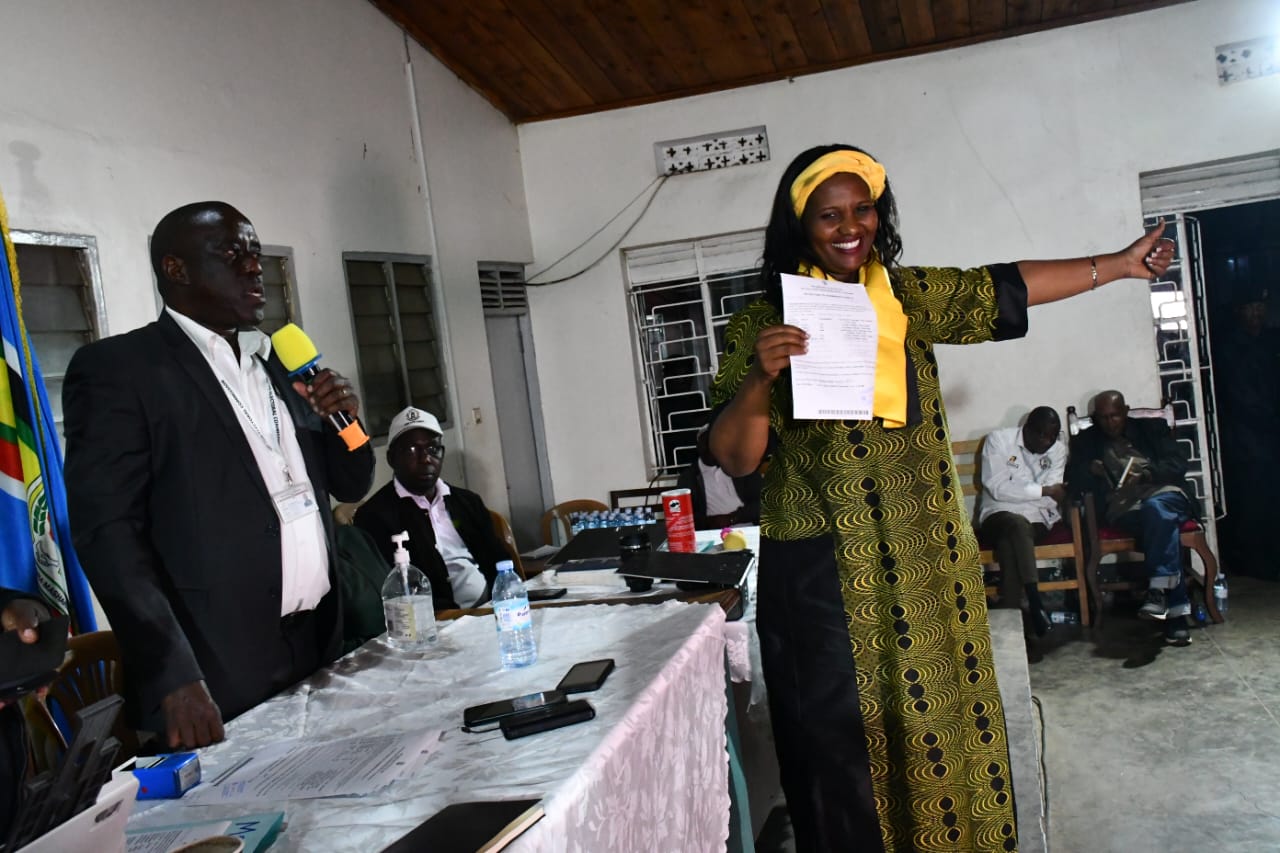

Trade Minister Amelia Kyambadde. PHOTO | FILE

Government has protested the ban imposed on Ugandan maize by Kenya that has left tonnes of grain stuck at the border, and traders staring at losses.

Minister for Trade, Industry and Cooperatives Amelia Kyambadde told journalists in Kampala yesterday that they are to issue a protest note, on grounds that the ban is being implemented on what she termed as rumours, with no scientific explanations to back up their claims.

The Kenyan government, through the department of the Agriculture and Food Authority banned the importation of maize from Uganda and Tanzania, saying the cereal had aflatoxins.

But according to the minister, neither her ministry nor that of East Africa Community (EAC) Affairs received official communication from Kenya regarding the ban.

Government wants Kenya to also produce evidence, including laboratory reports conducted by a certified body to back up claims that the maize does not conform to the EAC standards on aflatoxins.

“The protest note is to complain about the mode of interception or imposition of the ban. They should have given official communication, all these are allegations. We are grappling with all this but we do not know the facts. The ban and interception of vehicles was not subjected to any testing and some of them had already gone as far as Nakuru and they just blocked them and sent them back, without testing,” Ms Kyambadde said.

Ms Kyambadde said Kenya should have issued a warning before imposing the ban.

She was speaking after an inter-ministerial meeting attended by ministers of Agriculture, Finance and Foreign Affairs.

Yesterday, Burundi joined Kenya in imposing a ban on maize products although they did not clarify the affected countries.

The meeting also resolved to pursue dialogue to address the ban. Despite having suffered similar blockades on eggs, sugar, and milk, the minister has ruled out retaliation.

“Dialogue is the key to solve all problems. The issue of reoccurrence of these incidents is a matter for dialogue, we cannot talk about retaliation. We just have to continue dialoguing and consolidating other markets so that we divert from Kenya,” Ms Kyambadde said.

She added: “We are also seeking high level intervention between our two heads of state and a joint meeting which we intend to carry out probably next week.”

But the fate of the tonnes of grain intercepted at the border hangs in the balance. According to the minister, a way forward will only be reached after testing the maize by the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) since Kenya has not provided laboratory reports on the levels of contamination

“If they find that they are contaminated, they have to be disposed of. If free from contamination, we will seek appeal for the release of those,” Ms Kyambadde said.

UNBS executive director David Livingstone Ebiru said it will be impossible to establish when the maize was contaminated since it has been at the border for four days.

Mr Ebiru says they have 23 certified companies to export maize but acknowledged some cross without any testing.

He added that none of the certified companies has complained of being affected by the ban.

Ms Kyambadde also urged traders to shift focus to other markets like the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Africa Continental Free Trade Area.

Farmers’ Federation executive director Kenneth Katungisha said the government needs to set up laboratories at border points to assess the quality of maize and continue to sensitise farmers on good post-harvest handling.

He, however, said the ban is unfair and government should look for an alternative market.

“Aflatoxin and mycotoxins contamination across the East African region is an issue but that does not mean that all the food on the market is contaminated. The solution is for all countries to approach aflatoxins control and prevention as a region,” Mr Sam Watasa, Consumer Protection Association.

Aflatoxins

According to the World Health Organisation, aflatoxins are poisonous substances produced by certain kinds of fungi (moulds) that are found naturally all over the world; they can contaminate food crops and pose a serious health threat to humans and livestock.

Aflatoxins also pose a significant economic burden, causing an estimated 25 per cent or more of the world’s food crops to be destroyed annually.

Under favourable conditions typically found in tropical and subtropical regions, including high temperatures and high humidity, these moulds, normally found on dead and decaying vegetation, can invade food crops both before and after harvesting.