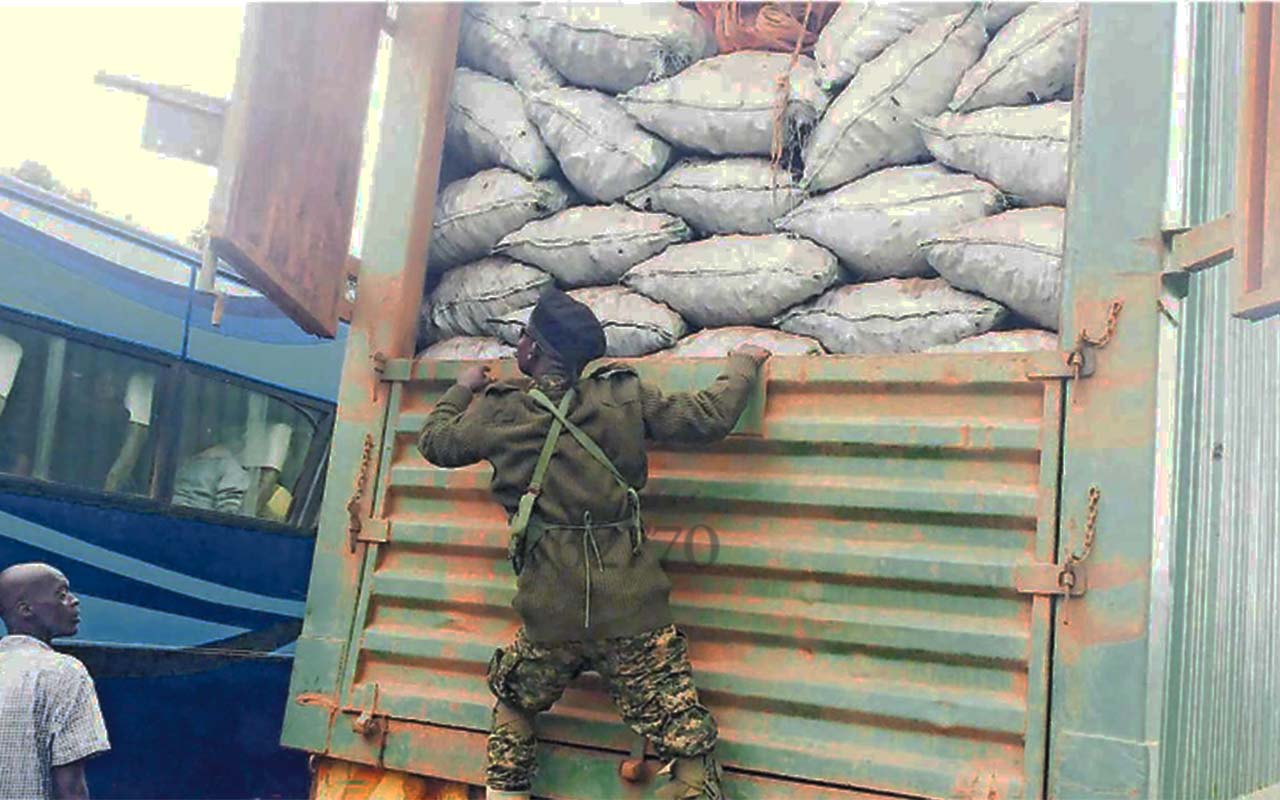

Military men surveil downtown Kampala on July 24, 2024 in the aftermath of the July 23, 2024 March to parliament protests which were managed by security forces with no reports of use of live rounds or teargas to disperse or arrest demonstrators. PHOTO/MICHAEL KAKUMIRIZI

The youth protests witnessed across several African countries are linked to high debt, experts say, reflecting how economic decisions by the ruling elite impact the poor.

Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria are among African countries facing youth revolt over the cost of living, largely blamed on fiscal measures by governments struggling to pay debts to local and foreign lenders.

In July, Kenyan youthful protesters, dubbed Gen-Z, took to the streets protesting against the Finance Bill 2024, which comprised punitive tax measures partly meant to raise funds to repay Kenyan’s debts.

The Kenyan protests have since morphed into general push for good governance in the public sector, even after President William Ruto shelved the contentious draft law and reconstituted the Cabinet.

The new team, meant to reflect the “diversity of the nation,” was sworn in on Thursday morning at State House, Nairobi, on the backdrop of demonstrations called by the youth.

Jason Braganza, executive director at African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (Afrodad), said the protests across the continent are partly because of the level of debt.

“This is because of the amount of borrowing that the governments are doing,” he said. “At the national level borrowing is a default tax, because, at some point in the future, the government is going to use taxation to raise revenues in order to pay that debt.”

It is tax proposals in the unpopular bill that sowed the protest seed. The Ruto administration argued at the time that it was trying to avoid defaulting on its loans and the new measures arose after it agreed to conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) before Kenya could get help to improve financial probity and reform its taxation regime.

A Kenya Police Officer fires a teargas canister during anti-government protests in Nairobi on July 19, 2023. PHOTO/AFP

Kenya’s public and publicly guaranteed debt stood at Ksh10.3 trillion ($79.3 billion) at the end of March, representing 67 percent of GDP, well above the World Bank and IMF’s recommended maximum of 55 percent.

The government had planned to raise additional revenue of Ksh346 billion ($2.68 billion), or three per cent of GDP, through the measures of the fallen bill. After it was rejected by the public, the government moved to cut spending on projects to cover for the lost revenue opportunity. Still, neither cutting spending nor taxing more are popular among Kenyans.

Most of Kenya's debt is owed to international lenders, while its biggest bilateral creditor is China, owed $5.7 billion.

Braganza notes that the Kenya government took very unpopular decisions around taxation because it preferred to continue borrowing to service debt and moved that burden to citizens and the citizens said enough is enough.

“There are issues of transparency, accountability and governance on how debt is utilised. It is important that, at the national level, we have systems that do not jeopardise the sovereignty and the rights of citizens when countries are deciding to take on debt,” he said.

“There is so much about debt. The commitment around debt is not helping much around the socioeconomic development of Africa,” said Faides Tembatemba, Action Aid Country Director for Zambia.

“Why is Africa borrowing when we have so much resource? What kind of negotiations are going on? There is so much injustice and inequality going on. This is fuelling the current protests by the young generation,” she added.

In Uganda, youth protesters recently staged rallies outside parliament against alleged corruption and human rights abuses by leaders.

Police and UPDF soldiers arrest more protestors in Kampala as Ugandans began a March to Parliament youth led anti-graft protest on July 23, 2024. PHOTO/ABUBAKER LUBOWA

Uganda's public debt has risen to unprecedented levels, reaching Ush96.1 trillion ($25.3 billion or 52 percent of GDP) as of June 2023, according to an Auditor-General's report released recently.

In Nigeria, protests kicked off on August 1, promoted online with hashtags such as #EndBadGovernanceinNigeria and #EndBadGovernance2024. The protests are aimed at holding President Bola Tinubu’s government accountable for economic mismanagement, corruption and other governance issues.

Apart from debt, the majority of African countries are facing governance, corruption and leadership issues.

At both the national and county levels, public officials allocate themselves funding for luxury vehicles, jet-setting lifestyles, new high-end housing and furniture or major facelifts for existing housing facilities including eight official residences for the President.

Prof James Gathii, Wing-Tat Lee Chair in International Law and professor of Law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, observes that lack of transparency when borrowing is partly to blame for the current protests in Africa.

“The reason we are likely to see this in other places is precisely the same: Huge debt burdens, which are unaccounted for in terms of real achievements on the ground,” Prof Gathii said.

“For instance, one of the Eurobonds (in Kenya) was never accounted for. There is a lack of transparency in how the debt was procured; it did not involve the citizens. This is also happening in other African countries where lack of transparency, poor governance, and corruption is the order of the day.”

In April, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said around 40 percent of the world’s population lives in countries that spend more on interest payments than health or education caused by a “raging bonfire of debt.”

“Look at the global financial system’s handling of debt. Many developing countries are being crushed under a steamroller of debt. Four out of every 10 people worldwide live in countries where governments spend more on interest payments than on education or health,” Mr Guterres said.

Annual debt service payments in the world’s poorest countries are 50 percent higher than they were just three years ago.

In sub-Saharan Africa, debt servicing consumed nearly half of all government revenue in 2023.

“Unless we take decisive action on debt and liquidity challenges, we risk another ‘lost decade' for many developing countries, putting the achievement of the SDGs by the 2030 deadline definitively out of reach,” Mr Guterres said.

*Originally published by the East African