Prime

Mayanja on how to set up govt to manage the state

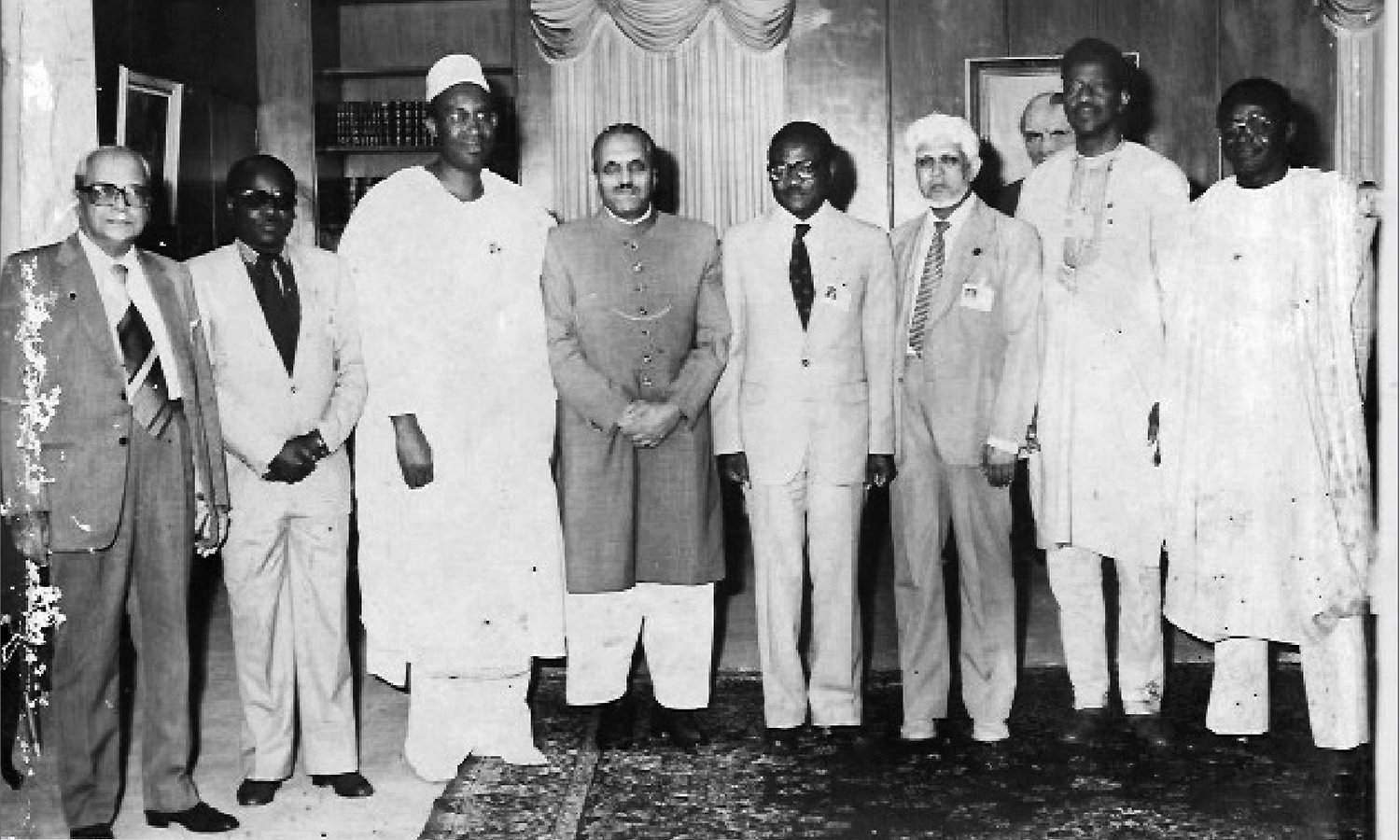

Abu Mayanja and other dignitaries. Photo/Courtesy

What you need to know:

- As a general legal framework for the organisation of a given society, Abu Mayanja argued that a constitution should not be changed or tampered with whenever there is a political problem. In his new book, historian Prof ABK Kasozi shows why Mayanja believed that a constitution is not a cure for every political problem.

Abu Mayanja thought that a constitution does not resolve major political or criminal problems, though having one helps structure laws.

“I want to make this point strongly that we should not change constitutions in the way some men change their shirts. The Constitution should be considered as a document at great sanctity. That is why we call it the fundamental law of the country, we should respect it, we should abide by it,” he offered during a plenary session on July 5, 1967 as the House contemplated the enactment of a new Constitution.

Mayanja started his lengthy speech [on the floor of Parliament] by asking several critical questions, including the following: What were the essential characteristics which every Constitution must have? What were the main issues a Constitution should address? In stating his review of the constitutional proposals and having dismissed the view that a constitution can be used to resolve every political problem, Mayanja went on to say what, according to him, was the primary role of a constitution in a state.

For him, the “…underlying philosophy of our Constitution is that all men are under the law, and no one is above the law.” For him, therefore, a constitution must balance the claims of freedom of the individual and the state’s interests, especially national security. Accordingly, a constitution must provide a government strong enough to govern while at the same time protecting the rights, liberties and freedom of the individual citizen.

As for the underlying principles and philosophical basis upon which a constitution fit for Uganda should be made, he thought that the following issues were critical [for Uganda]: national unity; freedom, loyalty to the state; preserving or creating the African personality; and preparedness to take risks of instability for enhancement of freedom and happiness of citizens.

National unity, freedom

He thought that national unity was vital for the country to define a shared vision. However, for him, unity did not imply total integration into one mega tribe. He preferred unity in diversity where each social group could retain its identity but willingly cooperate with others without loss of distinctiveness.

“The first necessity that we have to provide for is, of course, national unity; we must see that our Constitution guarantees for the people of Uganda, that they shall continue to exist as a nation in unity, and that any disruptive tendencies, secessionist movements or tendencies towards a Biafraism or’ any centrifugal forces are defeated,” he told the House.

For him, the constitution should provide for freedom, liberty and guarantee human rights because a nation of slaves cannot be a happy state.

“But, Mr Speaker, a nation of slaves cannot be happy, proud, prosperous, or progressive. Consequently, in our quests for national unity, we must never forget that it is the unity of free men that we are seeking,” he told a plenary session on July 5, 1967, adding, “We must never, in the attempt to achieve national unity, destroy the very objectives for which we want the unity, that is to say, to build up a nation of free men, proud men, happy men and women.”

Loyalty to the state

While he thought loyalty to the state was essential to the development of the Uganda postcolonial state, he realised two schools of thought about unity and integration of Uganda. These were (a) those who thought a Ugandan had to pay complete and exclusive loyalty to the state without mixing it with loyalties to other entities and (b) those who viewed loyalty in spreading out circles, including the Uganda nation, the tribes, religion and family.

He preferred the second category as the most practical one, given the country’s ethnic diversity. He thought loyalty to the nation was not mutually exclusive of loyalties to tribes, religion, family or local unions. In other speeches in Parliament, Mayanja developed the latter view by saying true unity does not require uniformity or sameness. The reality of Uganda is that different entities, ancient states and social groups existed before Uganda was packaged as a state for colonial administrative convenience starting from 1894.

He believed that most of the cultural heritage Africans have accumulated are the results of efforts of tribal political or social formations. For him, it was on those formations that the features of the African personality could be erected.

“There is one school which appears to say that in order to achieve true national unity, there must be one and only one loyalty in the country i.e. loyalty to the state of Uganda, or to the Republic of Uganda, as it shall be called after the passing of this constitution,” he offered, adding, “The second school of thought, Mr Speaker, is of those who conceive of loyalty in the series of expanding or spreading out circles.”

More than any other person, Mayanja recognised the political implications of forcing diversities of social groups into one boiling pot. Recent studies indicate that incidences of conflicts in Africa are exacerbated by the failure of post-colonial rulers to manage diversity.

Preserving the African personality

Most independent African nations would have liked to create the “image of the African personality.” Mayanja warned members of the dilemma of negating all aspects of tribalism, including the positive ones. He thought that in building the “African personality”, the new African state had few choices to choose from except looking at past achievements of Africans, which were mainly obtainable through looking at what pre-colonial African societies achieved as tribal organisations. These organisations or states were the custodians of African heritage. Short of that, African governments might create cultures that were imitations of Western or Eastern nations.

Mayanja warned his colleagues that states must not build dictatorial structures for fear of risks and instability. He felt that it was essential to accept that a state must face risks of instability to provide its citizens with a better life during its life.

Mayanja then went on to comment on those proposals that he thought fell short of expectations. He first listed the purported aims of the proposals and started some of his longest speeches in the Parliament of Uganda. He noted that according to what the President said, the purposes of the proposals were that they would provide for:

a) A broad-based structure of administration and political relationship understandable by all,

b) A democratic government,

c) A Government by consent,

d) The people as the source of power,

e) The equality of the citizens of Uganda and the elimination of privileges,

f) Equal sacrifices to be borne by the people of Uganda for our progress,

g) A responsible government that is responsive to the needs of the people and

h) A republican form of government.

Having narrated the above points, Mayanja pointed out in many words what he was later to summarise in the Transition magazine article that “Now I have very anxiously considered these proposals, I have gone over them, I have slept on them, I have turned them over in my mind and my considered conclusion is that in very many respects they fall short of the realisation of the above-mentioned objectives. And that is why I said that there was a dichotomy or chasm between what the President said as the government objectives in framing these proposals and the proposals themselves.”

Objections

Mayanja objected to the following areas: The inability of the Supreme Court to pronounce itself on the constitution; the number of MPs required for changing or altering the constitution (he thought 50 percent of the members were sufficient); distinctions amongst citizens by birth and registration; deprivation of citizenship; detention without trial; violation of the rights of citizens during periods of war or national emergencies; giving the state ability to acquire property for the public good; publishing names of detainees in the Gazette; the proposed increase of appearance of a detainee to the Tribunal from one to two months; the five-day period between the declaration of emergency and calling Parliament; the vagueness surrounding the term of the President contained in the proposals; among others.

The cover of Prof ABK Kasozi’s new book on Abu Mayanja. PHOTO/COURTESY

The book

The book breaks new ground in how Uganda and Africa have been viewed by academic and popular opinion. Mayanja’s life sheds light on the last days of colonialism and the early postcolonial history of Uganda and other African countries.

First, although Africa, particularly Uganda, is viewed by popular imagination through the images of dictatorial and corrupt African leaders like Amin, Obote, Mubotu, Bokassa, Bongo and others, there were, and still are, voices of reason who advocated for the advantages of good governance.