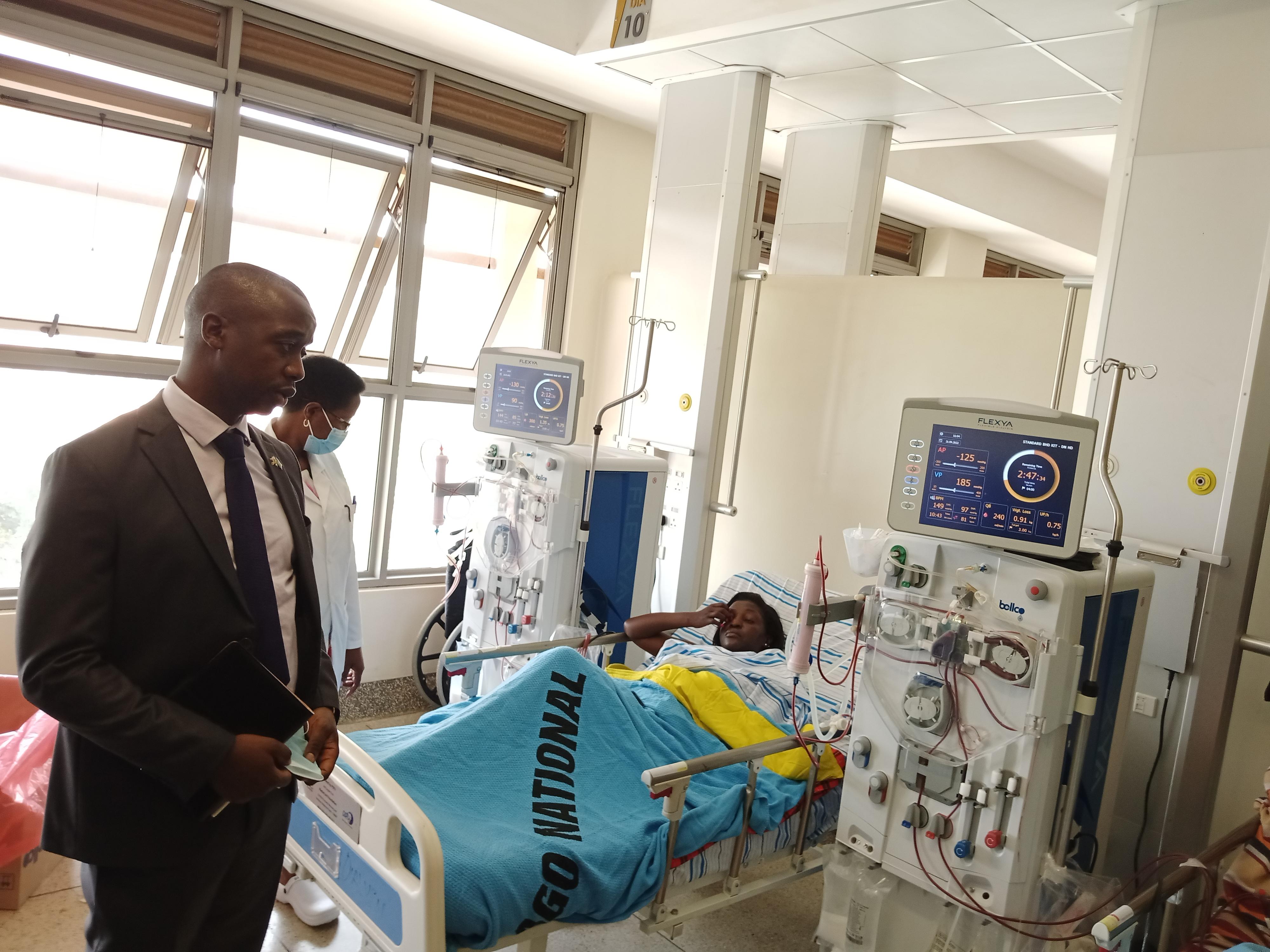

The chairperson of Parliament’s Health Committee, Dr Charles Ayume, and the director of Mulago Hospital, Dr Rosemary Byanyima, chat with a female patient at the dialysis unit on September 21, 2022. Photo | Tonny Abet

Irene Nerima, 30, a resident of Kampala, is one of the patients with end-stage kidney disease, who had hopes of getting a transplant at Mulago National Referral Hospital.

The successful kidney transplant in December 2023 at the facility raised hopes for Ms Nerima that she was likely to be a beneficiary of the complicated, life-saving procedure.

Other patients in her state have had to muster a minimum Shs80m and take a plane ride to Nairobi, the capital of the neighbouring Kenya, to have a kidney transplant.

It costs much higher, Shs200m, in India – a popular medical tourism destination for Ugandans with means.

Ms Nerima is not in the league of financially stable citizens. As such, the possibility of the procedure being conducted at Mulago hospital sounded more feasible for its closeness to home and comparably lower costs.

Then after three months of waiting and being upbeat, the bad news struck like a thunderbolt in dry skies: the government had applied brakes on kidney transplants at the national referral hospital, pending institution of a regulator and compliance with a litany of other technical requirements.

“I heard they [Mulago hospital] has suspended the transplant [services]. I am planning to go to the Aga Khan Hospital in Kenya for the transplant,” Ms Nerima told this publication.

She added: “The one (patient) they [transplanted] at Mulago was successful, I even saw the person. But I can’t keep waiting because time will reach when I will even fail to get money for dialysis and the more the toxin will build in the body [worsening the condition].”

Ms Nerima is part of the growing list of more than 30 patients who doctors at Mulago hospital said had expressed interest in undergoing kidney transplant at the facility. There are more than 1,000 people with end-stage kidney disease at the moment undergoing dialysis, according to government figures.

She said she had planned to get a transplant at Mulago hospital because the proposed cost of around Shs50 million would be lower than what is charged in Kenya, Turkey or India. She said before the suspension of the procedure which Uganda successfully trialed four months ago, doctors at Mulago had told her to prepare around Shs55 million.

“They told me in Kenya, I need around Shs80 million. While in India, a person who went there for a transplant told us that we need around Shs200 million for the transplant service,” she added.

Dr Simon Peter Eyoku, the head of Kidney Unit at Mulago hospital, told this newspaper that the suspension of the transplant is to allow the Health ministry reorganise and streamline the regulation of the transplant.

“Many people need the transplant. The budgeting process should go on, let us prepare our foundation. We have taken off, we have shown that we are able. So, we are now going to fix a few things that our eyes are open to. That is what the ministry is doing; having in place the authorisation committee, train them, put a proper system in place so that when we take off again, we are not going to look back,” he said.

Dr Jane Ruth Aceng, the Health minister, said they halted all Human Organ Transplant activities because they don’t have the Shs5 billion for the operationalisation of the Human Organ Transplant Council, the body that is supposed to regulate the activities.

She told Members of Parliament on March 27 that her ministry would spend Shs3.6 billion on training and benchmarking from other nations, whereas Shs1.4 billion would bankroll activities of the Council.

“We have halted all transplant activities because we need a Council in place. Yesterday, as you [MPs] were touring the surgical exhibition, you saw the ready facilities. They can’t operate unless we have a Council, and the Council has to be trained because it is virgin land in Uganda,” Dr Aceng said.

Section 13 of the Uganda Human Organ Donation and Transplant Act, 2023, which President Museveni signed into law in March 2023, provides for 15 functions of the Council. These, among others, include regulating, organising, and supervising the national organ, tissue, and cell donation and transplant; regulating designated transplant centres and approved banks; enforcing standards; regulating the allocation of organs; and, overseeing the national waiting list.

Private sector stuck

The announcement of the suspension also came after doctors in private sector complained that the absence of the regulator was rendering their investment in transplant field meaningless as they needed accreditation from the Council to start operating.

Dr Michael Okello, a liver transplant surgeon at Rubaga Hospital, said their facility is ready to start doing transplants, but they are stuck on accreditation.

“Most of us who the President sent, in 2017, to India for training, were in high-volume transplant centres. When we came back, there was no law but now that we have the law, we don’t have the transplant Council,” Dr Okello narrated.

He continued: “What our president [of the Association of Surgeons, Dr Frank Asiimwe] went through to have that [first] transplant done, people don’t know. But he had to run around, get approval –-- right now you can only get the approval from the minister [of Health, who is also responsible for appointing the transplant Council]. But for sustainability and continuity, we ask the Ministry of Health to at least have the transplant Council appointed so that other members can come on board.”

“Rubaga [Hospital] invested more than Shs1 billion to establish a state-of-the-art hospital based on our knowledge and guidance from what we saw in India. But to our dismay, our theatre is redundant waiting for the transplant Council to be appointed,” he added.

Commenting on the anomalies around organ transplant activities, Dr Charles Ayume, the head of Parliament’s Health committee, said they would support the ministry in ensuring the Council is up and running.

“We made the provision for the organ transplant Council and we put some money there. As a committee, we want to ensure we defend that budgetary allocation for the organ transplant Council. We have come a long way. We did the Bill, we did the first transplant in December and we need to functionalise it [the Council] because we don’t want to be taken to court,” Dr Ayume said.

He added: “In the Act, it is stated that no transplant will be conducted without the authority of the organ transplant Council. We really tried to ring-fence that law to make it a law of excellence in this region and when we set the bar high, it also encourages people to come here for medical tourism. We don’t want things done in a shambolic way.”

Dr Diana Atwine, the permanent secretary in the Health Ministry, said they would do everything possible to have the Council in place soon.

She said they need funds from government to “operationalise this Council as a matter of priority, a matter of urgency and a matter of national strategy”.

“[Members of] Parliament are part of us, they argue, ask for money but in the end when the final decision is made, they will tell you this is the money you have; so, sort yourself within the budget,” she said, “In this case, we will have to suppress some activities deliberately, and we find money to operationalise the Council so that these people [doctors] are motivated to continue working.”

She added: “Because they [doctors] have already demonstrated that they are able, they have built the skills, have the will, all they need is just us to facilitate them – put the right equipment, staff. But how do you do this without resources?”

Burden of disease

Health minister Aceng said “13 percent of the total population in Uganda” suffer from kidney problems, ranging from mild to severe. She noted that the mild stage can be managed by specialists, while the severe stage requires dialysis and eventually transplant.

“In Uganda, about two percent of the population have end-stage kidney disease and many of you are aware that non-communicable diseases are on the rise, 25 percent of the population are hypertensive. Similarly, diabetes and many other cancers are on the rise,” she said.

Mulago and Kiruddu hospitals provide the most dialysis sessions --- roughly 2,600 per month --- in addition to sessions at regional public referral and private hospitals.

In an earlier interview, Ms Nerima, who said she is awaiting kidney transplant in Kenya following the pause in the procedure at Mulago hospital, said she pays Shs150,000 per dialysis session (one a week) at the facility. That is significantly lower than the average Shs500,000 charged per session at some private hospitals.

Mulago hospital management said they charge for dialysis to allow for sustaining the services and servicing of the equipment as government doesn’t give them enough money for operations.

Dr Eyoku said contrary to the practice in Uganda, a patient with end-stage disease who is fit for transplant shouldn’t be on dialysis for years.

He said most people on dialysis are weak and may not be productive and yet a transplant, although expensive, can restore a person to health status which is close to that they had before the disease.

“Around 30 percent have acute kidney failure, which is likely to reverse and they can go off dialysis. But majority, 70 percent, have chronic kidney disease and they need dialysis for the rest of their lives. Again more than a third of these 70 percent are youthful patients below 60 years who can go for transplant,” he said.

“It should be government’s business to transplant in the shortest time possible where the patient contributes part of the money and the government gives the rest. If the person insists on continuing with dialysis, then they shouldn’t be given subsidised rate by government [currently at around Shs150,000 compared to Shs500,000 in private facilities],” he added.

Cause and prevention

Dr Robert Kalyesubula, the president of Uganda Kidney Foundation, said the major drivers of kidney diseases are non-communicable diseases like “diabetes, hypertension, chronic use of drugs such as anti-retroviral therapy, infections, and then sometimes cancers”.

“So, prevention relies on taking a personal interest. One, looking at our lifestyles, we should be able to do exercise. We should watch what we eat, particularly we need to eat a healthy diet, which is full of vegetables,” he adds.

The kidney specialist advises people to avoid taking raw salt in food, avoid excessive consumption of alcohol and go for regular kidney checks because some may not have symptoms.

“Just take, say, a urine test or a blood test and you know what your kidneys status is. If you have any of the above chronic diseases, you ask your doctor if you have these problems [of kidney disease],” he says.

Dr Kalyesubula advises particularly those most at risk not to smoke, drink alcohol or eat fried foods.

“These are key drivers of kidney disease,” he said, “We should also make sure we take enough water, eat enough fruits and we do exercise regularly.”

Kidney disease signs to watch out for

According to information from scientists, a person with chronic kidney disease (CKD) may not feel ill or notice any symptoms until the disease has advanced, hence the need for wellness checks.

The symptoms, according to specialists, can include foamy urine, urinating more frequently, itchy or dry skin, nausea, loss of appetite and weight loss.

For more advanced CKD, one may experience numbness or swelling in the legs, arms and feet, achy muscle cramping, shortness of breath, which can be life-threatening, vomiting, trouble sleeping and concentrating.

The head of Kidney Unit at Mulago Hospital, Dr Simon Peter Eyoku, advises Ugandans to always go for wellness checks.

“It is expensive to do a wellness checkup, but it is saving a lot of money in other countries. But in Uganda, finding someone who wants to be checked from head to toe, every end of year, is hard,” he said.

Our survey shows that an initial full checkup costs Shs1.5 million, while the charge for subsequent annual follow ups at the same facility is about Shs300,000.

“It is very reasonable but this is not the outlook that many Ugandans have,” Dr Eyoku said, “Many [kidney patients] come to us crawling [when very sick and] after trying all the herbal medicines and going to nearby clinics. We need to emphasise prevention.”