Members of the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral Namirembe march in a procession during Palm Sunday prayers at Namirembe Cathedral in Kampala on March 24. PHOTOS | FRANK BAGUMA.

For more than 87 years it has been in existence, the all-male choir of St Paul’s Cathedral Namirembe, has cast itself as the embodiment of Anglican identity in Uganda buttressed by strict ranked procedures and disciplinary code. The choir is so rooted in many families that it has members who have been a permanent fixture at the historical hill for about 50 years.

Mr Edward Ssekabunga, the oldest choir member, has been part of the choir for about 48 years. He started crooning ever since his parents brought him to the hill in the 1970s.

Five months after taking over the reins of Namirembe Diocese from the now retired Bishop Wilberforce Kityo Luwalira, Bishop Moses Banja stunned the Anglican community in Uganda recently when he dissolved a choir steeped in history. He cited indiscipline and impunity.

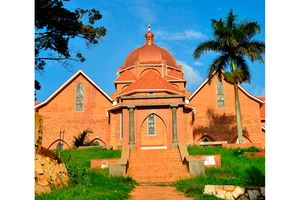

In an unusual tirade, Bishop Banja lectured the cathedral’s principal choir on ministry and evangelism, at least as understood in the Anglican Church tradition. The choir ministers in the striking 20th-Century red-brick minster designed by Prof Sir Arthur Beresford Pite, at least every Sunday morning, starting at 10 O’clock.

“Choral singing in the Church,” charged Banja, “is both a calling and a service to God. It is hardly soaked in theatricals or self-pleasure but rather about spreading the Good News to others, using our talents to exalt God.”

He went on: “Since my ascendancy to the bishopric, I have particularly observed in our cathedral that the choristers have greatly backslid in their service to God, especially in the 10 O’clock service, not least undermining the clergy, chiefly myself, the current bishop.”

Trouble in paradise?

This rebuke, which has since gone viral on social media in the form of an audio recording, seems to have emerged from the recently concluded meeting of the Diocesan Council, the working body of Namirembe’s Synod. A synod is a given diocese’s highest ecclesiastical organ with a legislative mandate. It comprises three houses—bishop(s), clergy, and laity.

Unlike suffragan, co-adjutor, and assistant bishops, Bishop Banja, like other diocesans, enjoys the right and privilege to chair both bodies whenever and wherever they may determine to sit, albeit per the Constitution of the Church of the Province of Uganda, the Canons of the Church of the Province of Uganda, and the Diocesan Constitution. During the aforesaid Diocesan Council meeting, it seems Bishop Banja drew up what looked like a charge sheet that contained four accusations against the choir.

The leaders of the choir have spoken to this writer on condition of anonymity, since they are not allowed to speak publicly. They vehemently denied the accusations and dismissed the bishop as misguided by the Namirembe Diocese Chancellor Fred Mpanga. Bishop Banja’s first accusation against the choir came after its members refused to sing during the requiem service of the Rt Rev Michael Ssenyimba, the former dean of Namirembe Cathedral. Also the former Bishop of Mukono and Vice Chancellor of Ndejje University, Rev Ssenyimba died on March 19.

The choir leaders, who spoke to this writer, confirmed that they didn’t sing but not because of rebellion as Bishop Banja suggested.

“The service happened on a school day. The service has boys and men. None of them is employed by the Church for the men who work. And for the boys, they are in school. It was a working day, but the Dean of the Cathedral sent out a message that they would be sent to send off Bishop Ssenyimba. Under normal circumstances, Bishop Ssenyimba should have been sent- off in Mukono because that’s where he was a bishop but the confirmation that there was to be service in Namirembe came six hours prior,” a senior choir member revealed, adding that the notification that called them said: “To those who can, come please come.”

The choir member told Sunday Monitor they couldn’t mobilise on short notice.

Namirembe Bishop Moses Banja preaches during a service at Namirembe Cathedral in Kampala on Easter Sunday on March 31.

“The choir had to inform parents in good time. And the people who work have to inform their employers. That didn’t happen,” a senior choir member, who has been part of it for more than two decades, said.

Not music to Banja’s ears

In the meeting, Bishop Banja rolled out another accusation, claiming that on Easter Sunday, he told the choir to sing a Luganda hymn titled Yimuka Ojje eri Yesu as a congregational welcome gesture to those responding to his altar call. He was clear about substituting the pre-planned recessional hymn, and for the organist to play the organ voluntary (music played as part of church service). Still, the pleas, the bishop alleged, fell on deaf ears.

The choir members interviewed insisted that Bishop Banja’s version isn’t accurate.

“That service is on YouTube. When you watch and listen carefully, you will realise that he didn’t invite the choir to sing. He began singing the song. When you begin to sing, musicians would want to wait for organists to give a proper key and some priests aren’t musical; they don’t give a proper key at the start of the songs,” a choir member said. “He didn’t invite the choir to sing. He began the song and when you listen to it properly by the second verse, the congregation joined in and sang.”

When this Easter service was ending, Bishop Banja said the choir refused to sing as the norm is in the Anglican Church, but the choir members still insisted it was far from the truth.

“Anglican tradition worship after the benediction, no one invites the organists to play the organ voluntary as the leadership and the choir exists,” a choir member said, adding that the true account was that the Rev Samuel Muwonge, the Namirembe Diocese Mission Secretary, right after benediction, stopped the cathedral’s veteran organist, Paul Lugya, from playing the organ voluntary on grounds that he had a communication to make.

Our source further revealed: “For a disciplined musician, it would be very hard to repeat this piece of music you would have been preparing for weeks. So out of anger, Paul didn’t play again. Now that’s an individual problem. It’s for Paul.”

Late arrivals

Still in his charge sheet against the choir, Bishop Banja referred to two separate marriage services on May 9 and 10. He said he was disturbed to witness the respective couples marching up the cathedral aisle without any accompaniment. In the first event, Bishop Banja said, Lugya, the organist, arrived mid-way through the vows, while in the next, there were only six choristers. The affected couples had already paid the requisite fees for such facilities.

In response to this charge, the choir members admit that on those particular days, some of their colleagues didn’t keep time. They, however, insisted that the bishop read much into it.

“That behaviour is not a pattern. It was a one-off. It was not a sign of disobedience,” the choir members told this writer.

We also understand that although the bishop says on the 10th the organist refused to play, the couple came with its music on a flash disk.

“The couple had chosen special music and decided to give it to the cathedral personnel. So, two songs were played and there was no need for the organs to play but because the bishop is being told the choir is undermining him, he just takes it the way it is,” we were told.

Unhealed wound

To many observers of Namirembe Cathedral, the tensions between the choir and Bishop Banja are the continuation of the questions being posed on the process that led to Bishop Banja replacing Bishop Luwalira. Many at the cathedral had concluded that one of their own, Rev Canon Moses Kayiimba, was the heir apparent of Bishop Luwalira.

Yet, after months in which allegations of fraud were levelled against those in charge of the process led to the appointment of Bishop Banja, it appears an old wound is still festering. Those who support Banja say his unexpected rise to the bishopric of Namirembe is perhaps his greatest ‘sin’. Ordained deacon in 1996 and priested two years later by then Namirembe Bishop Samuel Balagadde Ssekkadde, his service in Namirembe is interspersed with long periods of study leaves within and outside Uganda and ‘political exile’ in the neighbouring Diocese of Mukono.

As such many at the Namirembe Cathedral look at him as a ‘foreigner’ notwithstanding his roots at St Paul Cathedral Namirembe and in the Namirembe Diocese. Before being ordained as bishop, Banja had served as an assistant vicar at the cathedral before he went to serve as the archdeacon of Luzira Archdeaconry found in Namirembe Diocese.

This, according to sources, wasn’t enough to improve their perception of him among many churchgoers who were used to Bishop Luwalira being seen as the “son of the hill” and preferred Kayiimba to replace him.

The questionable process leading to Bishop Banja’s election to the episcopacy in which he edged out nine other candidates hasn’t done him any favour as his legitimacy is always questioned at the cathedral by those who didn’t support his candidature.

Banja’s opponents say under the stewardship of Mpanga, who is also dismissed as a foreigner on the Namirembe Hill—owing to the tenure he served as chancellor of Mukono Diocese—the process that catapulted Bishop Banja to the coveted seat was blighted by opaqueness, politicking, intrigue, accusations and counter-accusations, gagging, manipulation, and all manner of uncouth things.

Then Namirembe Bishop-elect Moses Banja (centre) is joined by members of St Stephen’s Church of Uganda, Luzira, in a march to celebrate his appointment, in Luzira, Kampala on November 20, 2023.

Mpanga denied these accusations, asking for proof. In the Anglican Church, a chancellor is a legal adviser appointed by the diocesan bishop. His roles include advising the bishop and diocese on secular and canonical laws.

Heir apparent that never was

Banja’s namesake and toughest ‘rival’, the Rev Canon Kayiimba, was, according to sources, not only a favourite of many at the cathedral but also senior choir members. It is not that Kayiimba has always been on Namirembe Hill. But unlike Bishop Banja, Kayiimba’s official release from Namirembe by Luwalira to West Buganda Diocese, formed in 1960, in 2020 to serve as ‘missionary’ diocesan secretary, appeared to be a political scheme aimed at preparing him to take over at Namirembe.

Sources familiar with Namirembe politics say Kayiimba’s installation as canon of St Paul’s Cathedral Kako, three years later, just a few months before the Namirembe ‘race’, was the ultimate unmasking of that plan.

Though things didn’t go according to plan, Kayiimba’s meteoric rise through the Church ranks had strengthened the hopes of his supporters; only to be cut short at the nomination stage. Since then, his supporters have insisted that this was also Mpanga’s scheme.

Although he had thrown in his hat for the Mukono bishop race a couple of months earlier, once Kayiimba was mysteriously locked out, Bishop Banja’s road was now clear.

The other candidate in the race, Rev Abraham Muyinda, the dean of Namirembe Cathedral, was no match for Banja. Kayiimba’s supporters insisted that Muyinda’s name was forwarded by Mpanga to the House of Bishops to make it easy for Banja to win.

“They knew Muyinda was too weak. That’s why his name was included. If they had included Kayiimba, he was going to beat Banja. Everyone knows that,” an elder at the Church told this writer on condition of anonymity.

Bishop Banja’s messy election and swift installation last year, making him the de facto dean of the cathedral, sealed the fate of his relations with some powerful sections of the choir and some congregants who don’t think of him very highly.

“You and I know it was never an election. The fraudulent process that brought him forth got him to question his esteem and reveal that he has not got many friends in the diocese,” a church elder said. “Most of the things he is doing aren’t of his making, but they are those of Mpanga. When you look at the charges against the choir, they have Mpanga written all over them.”

Turbulent past

Namirembe Cathedral has had a turbulent history. Since Bishop Leslie Brown, the rest of the native bishops have been Baganda, Uganda’s largest ethnic group, on whom politics beyond Church and the State are hinged. Yet Banja, the sixth bishop of the diocese, wouldn’t be the first bishop to have a run in with the choir. Bishop Misaeri Kitemaggwa Kauma (1985-94) and Luwalira, his protégé, had run-ins with this choir, but they never took radical steps to dissolve it altogether.

Counting from at least 1893, the choir, which got affiliated with the Royal School of Church Music in the UK in 1937, has certainly cemented its place in leading worship in the cathedral’s occasions of varied liturgical formats. These include Sunday services, evensongs, Thanksgivings, baptisms, weddings, ordinances, consecrations, installations, festivals (as based on the church calendar), requiems, memorials, inductions, and the famed special Advent Service of Carols by Candlelight in its 25th year, now—to mention but a few.

“No definite date,” writes John Musoke Ssekibaala in his book titled A Brief History of the Choir and Organ of Namirembe Cathedral, “can be ascertained for the founding of the choir, but apparently, the choir was a culmination of the continuous teachings of the Christian missionaries [like Alexander Mackay], whose routine work involved teaching European hymn tunes to their converts.”

By 1913, Ssekibaala says Namirembe (taking its name from the Ganda traditional deity for peace and tranquillity in the kingdom) had already overtaken the initial missionary station at Nateete, wrecked in 1888, as the main site of activity for Protestants in Buganda and beyond.

Namirembe Cathedral

“Although evidence exists of a group of native singers mobilised into a choir between 1897 and 1904,” writes Ssekibaala, “particular attention and emphasis on training a choir gained serious ground in 1905 [...] a development largely credited to C.W. Hattersley, an educationist C.M.S. staff with sufficient musical skills.”

“The all-male choir,” states the 2018 Order of Service of Carols by Candlelight: Nine Lessons and Carols, “leads the main service at 10am every Sunday throughout the year, which is conducted in the local language, Luganda.”

The choir maintains a tradition where members join at an early age and remain members for a lifetime. Little wonder, parents were shocked that the bishop dissolved the choir, albeit for 60 days.

“This week, we find that our parenting skills have to take care of mental health concerns seriously. We all have to be careful about the performance of the boys at the school in the coming term. This choir suspension decision is going to have far-reaching consequences,” a parent, who has sons in the choir, said.

Bishop Banja’s tenure will end in 2028, but this could be a long time for many Namirembe cathedral-goers.

“He will only be here five years, but we can’t wait for him to go,” one of the regular churchgoers told Sunday Monitor.