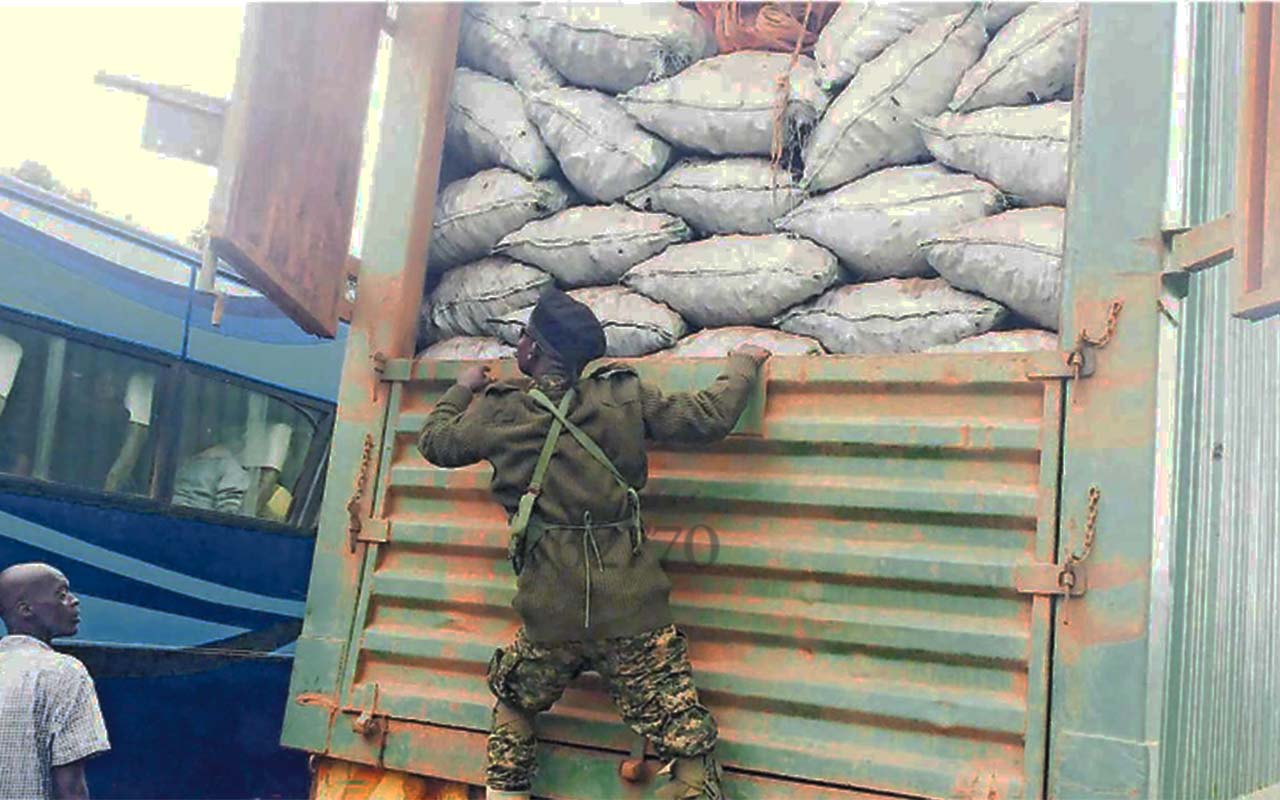

UPDF soldiers during Operation Shujaa in the DRC. In January 2023, then Defence Minister Vincent Ssempijja, told Parliament’s Defence Committee that his ministry urgently needed Shs21.5b for the mission. PHOTO/FILE.

The M23 rebels continue to seize large swathes of territory across the North Kivu theatre, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), after a renewed phase of fighting reawakened the spectre of a regional war.

Viewed as Africa’s sick man, the current cycle of violence in the DRC is a confluence of the lasting vestiges of colonialism—the role of brigand militias across the local and transboundary landscape; mercenary cut-throats seeking a slice of the vast mineral wealth and an unmoored United Nations Stabilisation Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO).

Ishasha, a town that lies on the Uganda-DRC border, fell into the hands of the largely Tutsi ethnic militia this week, without much resistance after the ragtag DRC government soldiers fled.

Uganda currently has thousands of troops in the restive eastern DRC under a bilateral treaty with Kinshasa to flush out the Ugandan-bred Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), which has committed massacres in the DRC and is seeking to build a cordon-sanitaire to prevent attacks from the neighbouring country.

In January 2023, then Defence Minister Vincent Ssempijja, told Parliament’s Defence Committee that his ministry urgently needed Shs108.2 billion to facilitate the deployment of 2,000 Ugandan troops to eastern DRC under the auspices of the Eastern African Standby Force. Another Shs21.5 billion, Mr Ssempijja revealed then, was needed for Operation Shujaa.

Almost a year after the deployment, in December 2023, the regional force, which included troops from Kenya and South Sudan, began its withdrawal from the DRC after Kinshasa deemed the deployment ineffective and refused to renew its mandate.

M23 was in 2012 hatched in the belly of a ruthless counter-insurgency campaign in eastern DRC with the support of allies in the Great Lakes to reportedly protect minority groups facing the spectre of ethnic cleansing. A recent UN report accused Rwanda and Uganda of supporting the rebel group, which both countries denied. It specifically fingered Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda, as Kampala’s major interlocutor who has been keen to “scout diplomatic support for the rebellion.” But Mwenda says his role in attempting to find a lasting solution to the conflict was not secretive and Kinshasa was aware of his meetings.

The latest fighting, however, threatens to turn the eastern DRC into an ethnic tinderbox, pitting ultra-conservative groups in the country against minority ethnic groups. Afflicted by the paradox of plenty, the DRC’s mineral wealth hidden in the bloodstained bowels of its earth continues to power the global engines of the fifth industrial revolution.

Dark past

The country remains captive to its colonial past after the royal decree on May 29, 1885 passed by King Leopold II, named the Congo Free State, a Belgian colony. The DRC is yet to heal from the scars of Leopold’s scorched earth tactics and snider rifle, which resulted in the deaths of thousands and the plunder of resources, including ivory and rubber through the reliance on state officials and their African auxiliaries.

A journalist, Joseph Conrad, captured Leopold’s brutality, which was one of the darkest chapters of colonialism, in his novel titled Heart of Darkness where he depicted an ivory procurement agent, Kurtz, a swashbuckling officer, who had a penchant for displaying a row of severed African heads around his garden. In the book titled King Leopold’s Ghost, the author, Adam Hochschild, writes: “College professors who have discussed this book, Heart of Darkness by Conrad, the genocidal scale of killings of the natives in thousands of classrooms over the years tend to do so in terms of Freud, Jung, and Nietzsche; of classical myth, Victorian innocence, and original sin; of post-modernism, postcolonialism, and post-structuralism.”

Leopold proclaimed: “In dealing with a race composed of cannibals for thousands of years, it is necessary to use methods, which will best shake their idleness and make them realise the sanctity of work.”

This slaughter continued in the post-colonial era during the reign of Mobutu Sese Seko’s kleptocracy—a cold-war stooge of the West, who left the country in dystopian ruin after the death of Patrice Lumumba, the charismatic first post-independence prime minister killed in 1961 through a suspected CIA-Belgian covert operation; during the Mbadaka massacres in the eastern DRC under the command of the Allied Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) rebellion led by Laurent Kabila and his erstwhile Banyamulenge allies—later assassinated by Banyamulenge Kadogos (child soldiers) and during the intractable regional conflict, which sucked in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zimbabwe, Angola and Chad, among others.

Laying down the gauntlet

As the DRC’s President Felix Tshisekedi prepares for a large offensive against the M23 rebels next month, the latest round of fighting could evoke the bitter memories of Africa’s ‘first world war’ between 1996 and 2001, which led to the death of millions of Congolese, lying in desolate graveyards across the green jungle of Africa. Faced with an election and a wave of national jingoism, Tshisekedi, in December last year, made a bellicose statement against Kigali at the rostrum. “If you re-elect me, and if Rwanda persists with its aggression, I will request Parliament and Congress to authorise a declaration of war. We will march on Kigali. Tell Kagame, those days of playing games with Congolese leaders are over. I will not tolerate these provocations.”

Whereas relations between Kigali and Kampala have recently thawed, in 2022, Uganda was ordered to pay $325 million as part of reparations to the DRC after it was found guilty of war crimes and plunder, among others in the Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo filed at the Hague-based International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Earlier in May 2001, the Justice David Porter-led Judicial Commission of Inquiry found a few high-ranking government officials, including the president’s brother, Gen Salim Saleh, his wife Jovia Akandwanaho, and the late Army Commander, Maj Gen James Kazini, guilty of some accusations levelled against them by the UN panel of experts, which had earlier on probed the plunder of DRC resources and fingered the trio as part of a tangled web that was part of an elite network in the areas controlled by Uganda, which was meant to exercise monopolistic control over the area’s natural resources.

Pillaging the DRC

The UN report alleged that this cartel relied on the transnational criminal group led by the Russian arms trafficker, Victor Bout. For nearly two decades, Bout grew infamous as the merchant of death—his nom de guerre for the black-market weapons deals for which in 2011, he was convicted in a US federal court and sentenced to serve 25 years in jail. In December 2022, Bout was freed in a prisoner swap with a US female basketball star, Brittney Griner.

Bout, according to the UN Panel of Experts report, purchased the Uganda-based non-operational airline company Okapi Air. The purchase of the company allowed Bout to use Okapi’s licences. The company was subsequently renamed Odessa. The Panel claimed that it had a list of outbound flights from 1998 to the beginning of 2002 from Entebbe International Airport, which confirms the operational activities of Bout’s aircraft from Ugandan territory.

The others, including Internal Affairs Minister, Maj Gen Kahinda Otafiire and the late Brig Noble Mayombo, then Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence boss, were exonerated by the Porter’s inquiry.

Uganda paid the first instalment of these reparations worth $65 million to the DRC in September 2022.

Positives

On a brighter note, DRC is now part of the East African Community (EAC) bringing on board a market of 109 million persons and opening another frontier for the region across the Atlantic Ocean.

In January, Uganda registered the highest trade surplus with the DRC amounting to $53.07 million (Shs197 billion) in January, according to the Ministry of Finance Performance of the Economy report.

The report, which highlights the monthly performance of different sectors of the economy, noted that the DRC received more exports from Uganda than any other East Africa Community (EAC) member state, followed by South Sudan at $41.68m (Shs154b), Rwanda $23.1m (Shs86b) and Burundi at $5.25m (Shs19b).

Uganda, however, reported deficits with Tanzania of $88.41m (Shs328b), and Kenya of $12.39m (Shs46b). The Government of Uganda doled out $335m (Shs1.2 trillion) to a private road construction firm, Dott Services Ltd, to build 223km of tarmac roads which could prop up cross-border trade in the neighbouring country that is littered with deep-rutted highways and has a tarmacked network of a paltry 3,000 kilometres.

Zoonotic diseases

A child with mpox. PHOTO/FILE

As thousands of civilians continue to flee the war-wrecked eastern DRC into Uganda, including ‘pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers and young children’ the fluid nature of the border makes the spread of diseases, including Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Ebola hemorrhagic fever and mpox, easy.

Uganda recently announced the detection of two cases of mpox in the western district of Kasese. The cases were among six suspected infections in Mpondwe and Bwera, towns bordering the DRC, according to Henry Mwebesa, the director general of Health Services at Uganda’s Ministry of Health, in a statement issued in Kampala. He said samples from a 37-year-old Ugandan woman married to a Congolese national, and a 22-year-old Congolese female, tested positive for the viral disease.

During the last Ebola outbreak in October 2022, Health minister Jane Ruth Aceng told journalists barely after a closed-door meeting with several donors and officials from the World Health Organisation (WHO) that Shs68b, which the ministry was seeking to combat the spread of Ebola, was less of the required financial war-chest.