Young men nap the afternoon away at the Railway grounds. Many people who have no jobs tend to idle their time away. Photo by Abubaker Lubowa

Uganda’s economy continues to show signs of resilience. Inflation, at 3.2 percent in the 12 months to May, is one of the lowest in the continent, although the Central Bank expects it to rise and settle at around five percent by the end of next year. The shilling has been relatively stable against the US dollar, helping to keep inflation low.

Some of it is down to competent stewardship; Kenya’s shilling lost about 20 percent of its value against the dollar in 2023 according to Bloomberg, a financial data firm, weighed down by foreign-denominated borrowings. As banks in Nairobi hoarded the green buck, business executives in Kampala had no problem accessing dollars.

Part of it is down to good fortune. Favourable weather and resultant good harvests kept the prices of most food items down. Compare that with Zimbabwe and Egypt, for instance, which saw food inflation of 26 and 18 percent respectively in February 2024.

The oil and gas sector promised a headline $10.2 billion in foreign direct investment in 2022 with the promise of 6,300 jobs, according to a policy brief by Ernst and Young, an audit and business support firm, compared to $2b in Kenya and $1.3b in Tanzania in the same period. This number, however, appears more of a hopeful projection; other data show that FDI, as a share of GDP, has dropped from 6.7 percent in 2007 to 2.3 percent in 2020 as risk-averse money seeks derisked investments elsewhere.

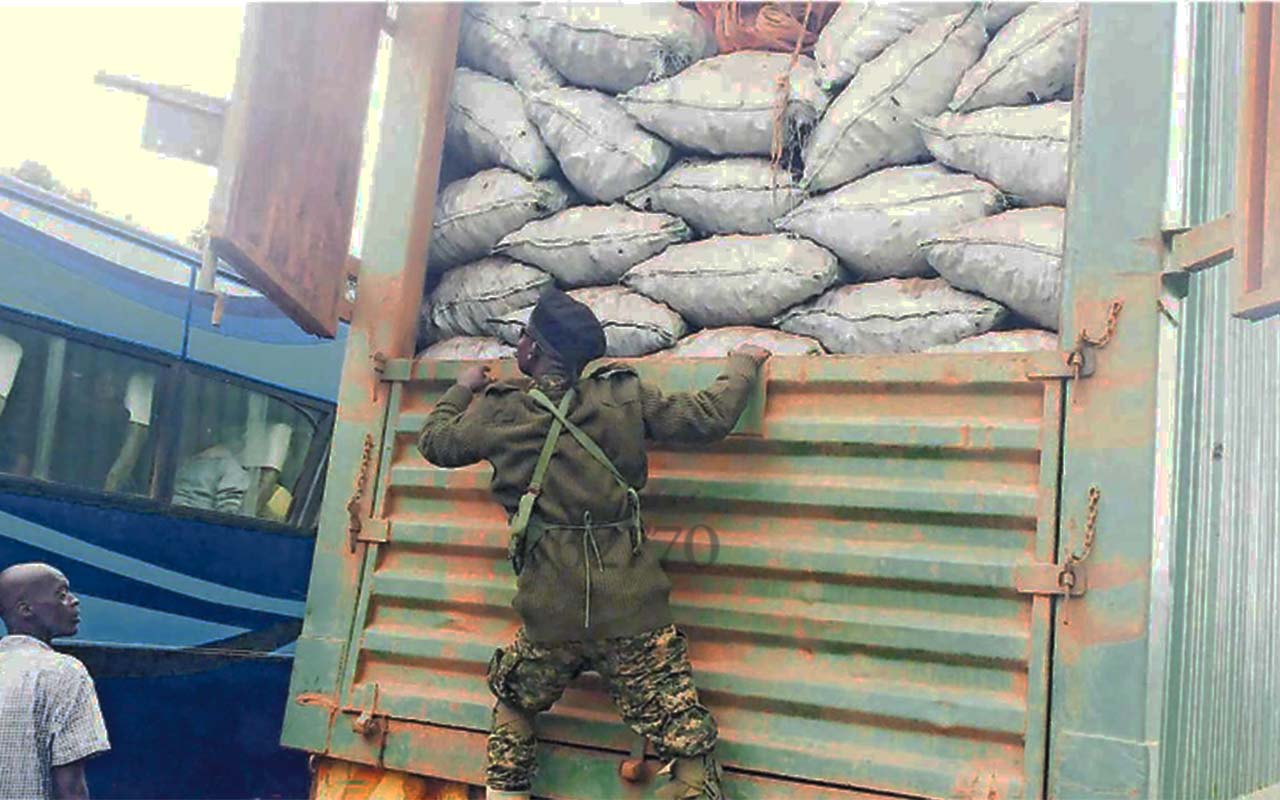

Look closely and you can see the tears in the fabric. Uganda’s merchandise exports increased slightly to $634m in March 2024, according to the latest figures from the Ministry of Finance, but the leading exports – coffee, gold, tobacco, simsim, hides and skins – have low value added to them.

Merchandise imports grew faster over the same period to just over a billion dollars, as the country continued to import vegetable products, beverages, plastics, rubber and related products, and other manufactures. As a result, Uganda’s trade deficit with the rest of the world expanded by almost half to $403m in March, from $277m in the previous month.

Other indicators show the stress points. At Shs2.2 trillion, total revenues and grants in April fell short of the target by almost Shs400b. Tax and non-tax revenues fell short by Shs252b, adding pressure to a fiscus already suffering from funding cuts due to a falling out with traditional development partners.

Despite the shrinking of the cloth, the government continued to make oversized coats, spending Shs471b above budget in the same month on recurrent expenditure. By spending money it had not collected, the government ran a fiscal deficit of Shs1.3 trillion in April, against a target of Shs405b. Public debt has risen sharply over the past decade as the country appears to spend some of its oil and gas revenues before they materialise.

While month-on-month and year-on-year figures are interesting, they are not illustrative. To see the bigger picture and the tears in the tapestry of the Ugandan economy, one needs to zoom out for a wider and more long-term view.

Comparison is the thief of joy, and historical juxtapositions of countries say 50 years ago and where they are today can often miss important idiosyncrasies like outbreaks of political instability or fortunate discoveries of natural resources. Yet they are hard to avoid and could be a useful way to show the impact of bad economic policies and political choices.

The countries that have made giant social-economic transformations over the past four decades – think China, South Korea, and Vietnam, for example – were able to double their GDP, a measure of the goods and services produced in an economy in a year, every 16 years.

In 1995, when Uganda’s economy grew at 8.5 percent, there was a sense that it, too, could follow these Asian Tigers. However, GDP growth slowed to 7.6 percent in 2006 and 6.3 percent in 2011. That now appears to have been an inflection point and Uganda’s economy has since lagged behind neighbours like Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Asian Tigers long disappeared into the distance.

A stubbornly high population growth rate, propped up by a combination of public pronouncements encouraging large families and lukewarm support for family planning initiatives, has locked the country in a vicious cycle of poverty. The population poverty rate dropped from 24 percent in 1989 to 7.3 percent in 2019 – but the number of Ugandans living below the poverty line increased from 10 to 18 million over the same period. There are eight million more poor Ugandans today than 30 years ago.

Uganda is falling behind on many social-economic indicators such as education and health. With the deadline for the Sustainable Development Goals only six years away, only 26.2 percent of the targets are on track or have been met; there is only limited progress on more than half; and we are getting worse on about 20 percent of them.

This is the state of the nation. Several government initiatives have been launched in the name of “poverty eradication”, “prosperity” or “wealth creation” but the results do not reflect the energy. Two-thirds of respondents to an Afrobarometer survey in January 2022 said the economy was “fairly bad” or “very bad”, up 20 percent from 2019. In the same survey, six out of every 10 respondents said their personal living conditions were “fairly bad” or “very bad”, up 17 percent from 2019.

Increasingly, many young people are questioning the ability of the current programmes to deliver social-economic transformation. Afrobarometer pollsters found that only 48 percent of youthful respondents aged between 18 and 30 believe that the country is headed in the right direction.

Resilience is not growth. For Uganda to meet its full potential and that of its citizens, it will have to think and do things differently, a lot faster, and a lot better. The economy is a good place to start.