Celine Nalwanga, mother of two sticklers. PHOTO/DOROTHY NAGITTA

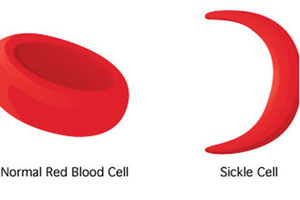

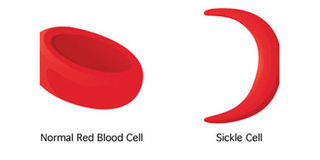

Fifty-year-old Celine Nalwanga, a resident of Kayunga Village, in Wakiso Town Council, is one of many parents grappling with the challenges of raising children with sickle cell anemia. At 28, she gave birth to a healthy baby girl. However, by the age of seven, her daughter began showing symptoms of sickle cell anemia, a genetic disorder affecting red blood cells.

“One time, she had yellow eyes. A sickle cell test was carried out at Kayunga [Regional Referral] Hospital. The results were positive. At the time, the words ‘sickle cell’ were disheartening. At first, my husband did not believe the diagnosis but we later began getting medication at Mulago [National Referral] Hospital,” she says.

Ms Nalwanga says it was a challenging time because the child needed attention and treatment, which is quite expensive.

“A fever affected her legs and she couldn’t walk. The doctors advised us to give her crutches, which I did not support. Instead, I made sure she exercised daily. With time, she recovered. You have to have Shs100,000 set aside everyday for emergency medical bills. For someone who earns very little, the financial distress can be overwhelming,” she says.

Due to the extensive care needed for their first child, the couple delayed having another baby. In 2011, they welcomed a second child, who was also diagnosed with sickle cell anaemia

“I remember my husband saying, ‘All the children we are producing are useless.’ This statement hit me hard. He stopped supporting the family. My husband and I have the same blood group O, but I suspect the disease is on my husband’s side because some of his relatives have it. He later abandoned us,” she narrates.

Statistics

World Health Organisation (WHO) data indicates approximately five percent of the world’s population carries trait genes for hemoglobin disorders, mainly, sickle cell disease and thalassemia.

Worldwide, more than 300,000 babies with severe hemoglobin disorders are born annually globally.

According to the Ministry of Health about 250,000 people are living with the disease and 20,000 babies are born with it annually, of which at least 50 percent die before reaching the age of five.

Dr Phillip Kasirye, the head of Mulago Sickle Cell Clinic, highlights the clinic’s efforts since its inception in 1968.

“On average, we have an annual active population of about 5,000, while the daily population ranges from 100 to 200 patients. The sickle-shaped cells cannot deliver oxygen to parts of the body and this causes sudden attacks of severe pain in the legs, fingers, hands and other body parts. These pain crises can occur without warning,” he says.

Although Mulago Sickle Cell Clinic provides access to most recommended medicines, including the folic acid, painkillers, and hydroxyurea, Dr Kasirye admits more needs to be done.

“We do not yet have the adequate services to meet the ever-growing population of sickle cell sufferers, but, at least, they are privileged (to have what we can offer). There are facilities, especially the lower-level facilities, which are not identified to receive some of these key medicines yet. However, we have more than 80 sickle cell clinics across the country, mainly at the referral and district hospitals,” he says.

Due to the expenses incurred in managing the disease, the paediatrician advises couples to take a sickle cell test before entering into a relationship.

As a single mother, Ms Nalwanga dealt with stigma in the community and at the schools she enrolled her daughters.

“Some people used to tell me that paying school fees for my children was like investing in a business that is going to collapse anytime. They had been told children suffering from sickle cell disease die young. But, my first child graduated this year with a Law degree. I had to set up my own school for two reasons; one, to provide stable employment for me since I used to take many days off to take care of the girls. Secondly, I needed to provide employment for my daughters when they grew up, so they wouldn’t face stigma in the workplace,” she says.

Similarly, 34-year-old Ashraf Ssebandeke, a sickle cell advocate, finds it challenging to find a partner.

“People don’t understand that we can have relationships. Families often discourage their daughters from marrying someone with sickle cell disease,” he says.

Ashraf Ssebandeke, the founder of Action Against Sickle Cell, shares his story with our reporter Dorothy Nagitta,

Mr Ssebandeke, who has spent 19 years raising awareness about the disease, was motivated by the harsh stigma he faced in high school.

“One time, when I had just returned from sick leave, the Fine Art teacher gave me an assignment. I could not perform it because of the pain in my fingers. He did not listen to me; instead, he punched me on the head and confiscated my sandals, which I was wearing because of the pain in my toes. Unfortunately, some teachers thought I was faking the pain,” he says.

In 2017, with this sad memory, Ssebandeke established a foundation, Action Against Sickle Cells, to help children and students who face stigma.

A call to action

Today, as the world commemorates sickle cell day, Dr Kasirye urges communities and NGOs to join the sickle cell awareness campaign.

Mr Ssebandeke emphasises the need for more medical personnel and resources to handle sickle cell patients. “I advocate for pre-marital counselling policies to ensure couples undergo screening and counselling. Despite our community screenings, consistency is lacking,” he says.

Mr Ssebandeke says despite his organisation’s relentless efforts against the disease, challenges such as inadequate medical personnel to handle sickle cell patients in hospitals and limited resources, are still a burden.

“I advocate for pre-marital counselling policies, so intending couples can undergo screening and counselling. Despite our community screenings, consistency is lacking as people continue to marry and procreate daily,” he says.

In the same way, Ms Nalwanga requests the government to increase provision of sickle cell medicines as well as laboratory equipment such as complete blood count (CBC) equipment for sickle patients in their clinics.

She adds that the government should hire sickle cell counsellors in schools; in the same way it hires HIV and albinism counsellors.