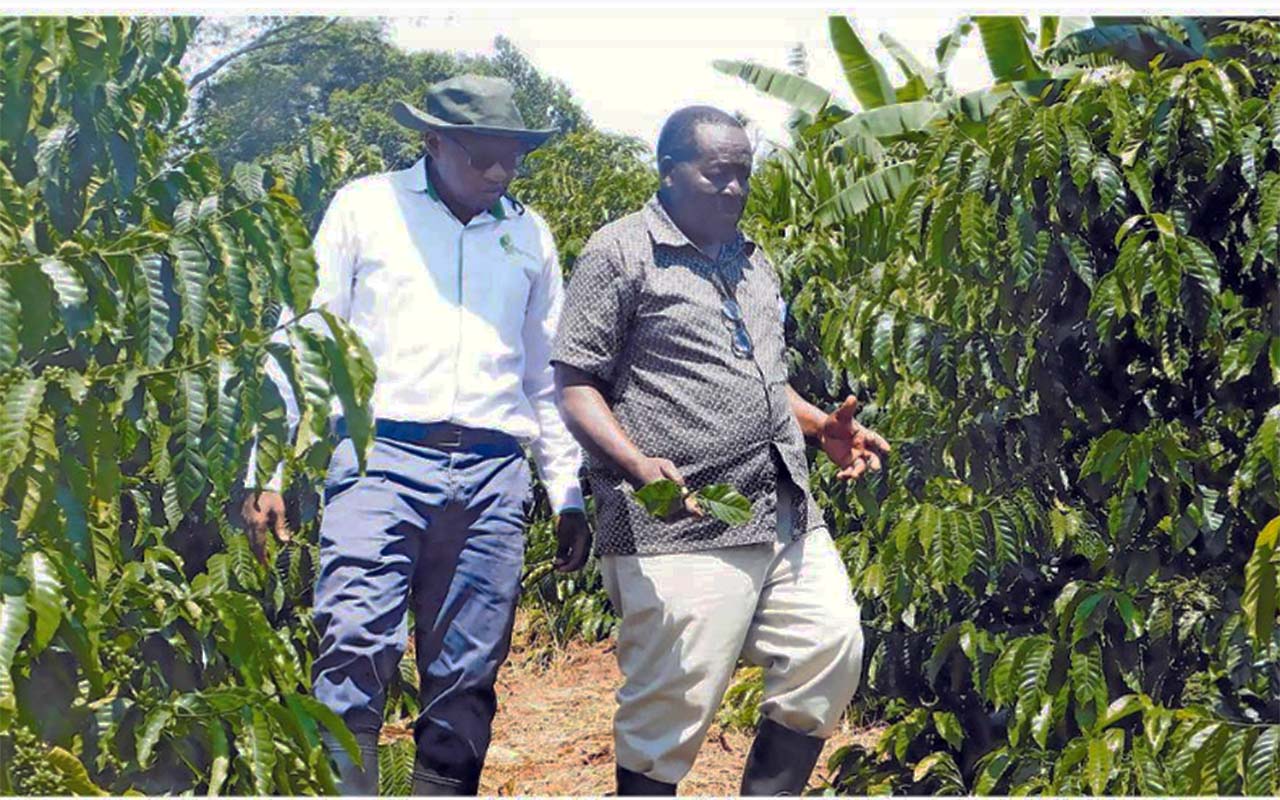

A coffee farmer savours the fruit of his crop. PHOTO/ GEORGE KATONGOLE

The contested 2011 elections results brought with them good news for the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party.

Not only was President Museveni competitive in Kampala but the party’s councillors dominated City Hall, getting in Godfrey Nyakana (Kampala Central) and Ben Kalumba (Nakawa)—two division mayors.

The party also bagged three parliamentary slots in Fred Ruhindi (Nakawa), Muhammad Nsereko (Kampala Central) and John Ssimbwa (Makindye East).

Yet by 2014, Ssimbwa—who had won a constituency that is historically an Opposition bastion—was warning that NRM’s prospects in Buganda were doomed. Ssimbwa located NRM’s troubles in Buganda to rural poverty that isn’t captured in the economic growth statistics cited by Mr Museveni.

Ssimbwa also pointed out that land conflicts slimmed NRM's chances in Buganda. Many people, he warned, had been left homeless following evictions that were carried out on government orders.

Ssimbwa also said unemployment among the youth, who consequently resorted to betting, was a huge challenge. All programmes targeting youth, he further noted, were not benefiting the intended beneficiaries.

Not done, Ssimbwa described his party's response to challenges facing the country as “reactive,” an approach he said works in favour of its opponents. He told the NRM to adopt “a proactive strategy” and stop waiting for people to vote against it to listen to their concerns.

In the subsequent 2016 elections, Ssimbwa got 7,733 votes as he failed to hold onto his Makindye East seat. He eventually finished distant third, with Ibrahim Kasozi of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) party emerging winner. Despite Ssimbwa’s failure and grim pre-election predictions, the NRM party generally won the rural precincts in Buganda. It took more than five years for Ssimbwa’s apocalyptic forecast to materialise, with a nascent party—the National Unity Platform (NUP)—led by Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, alias Bobi Wine, doing the damage.

Losing Buganda

Museveni had won Buganda ever since presidential elections were reinstated in 1996. Bobi Wine, according to the Electoral Commission’s (EC) official data, won 62.01 percent of the vote in Buganda, while Museveni got a paltry 35 percent.

Whilst Museveni attributed Bobi Wine’s dominant display in Buganda to sectarianism, his then Minister for Presidency, Esther Mbayo, was more direct. She attributed NRM’s loss in Buganda to the Catholic Church and Buganda Kingdom Katikkiro (prime minister) Charles Peter Mayiga. Mr Museveni’s minions said during the campaign, Katikkiro Mayiga used coded language, telling people in Buganda to only vote for ripe coffee. The colour of ripe coffee is red, which also happens to be the official colour of NUP.

A farmer in Bunyangabu spreads out coffee. The smuggling of coffee had intensified in the 1970s. PHOTO/MICHAEL KAKUMIRIZI

Now, a year before Ugandans go to the polls in 2026, with Mr Museveni looking to extend his presidency into a fifth decade, coffee has yet again emerged as a key election issue. At least in Buganda where it has pitted Museveni’s establishment against Mengo's establishment and the Opposition.

Going against the advice of the Buganda Kingdom, Mr Museveni’s NRM used its sheer majority in the House to eliminate the Uganda Coffee Development Authority (UCDA). Katikkiro Mayiga had earlier tried to make a case for saving UCDA by connecting to Buganda’s Emmwanyi Terimba Initiative, which he says was started in 2016 as a means of addressing the poverty “we witnessed during the Ettoffaali Drive (fundraising).”

Katikkiro Mayiga said further UCDA joined the Buganda Kingdom and provided 10 million seedlings and extension services. These, he said, led to improved crop quality and quantity.

“Selling our coffee without value-addition results in lower earnings. However, even wealthier Brazil and Vietnam, which grow more coffee, also sell “kase” because the large European and American markets consume freshly ground coffee at the end consumer outlet,” Mr Mayiga said, adding that UCDA should be funded further and retained to advise on good farming practices; improve quality of the crop on the farm and after harvest; raise the quantities produced; popularise the drinking of coffee; and explore possible bi-products from the coffee bean.

Rationalisation

Mr Museveni has had a different view from that of Mr Mayiga. The President, for starters, says the move to eliminate UCDA is part of the cost-cutting process his government is undertaking. Rationalisation, Mr Museveni says, “means removing the irrationalities in the production process—things that are not reasonable must be done away with. This is what happened in other parts of the world when people were waking up to, for instance, the irrationalities of feudalism and beginning to understand the power inherent in private–sector-led growth, articulated clearly by, for instance, Adam Smith in his very useful book titled The Source of the Wealth of Nations of 1776.”

Museveni went on to entirely dismiss any impact that UCDA had made in the coffee sector, saying the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (Maaif) will now take over the role of the dissolved Authority.

Speaking of Maaif’s competencies, the President rhetorically asked: “Who defeated the cassava mosaic? Who defeated kajuunde (the banana wilt)? Who defeated the coffee wilt? Who has been defeating the livestock diseases like CBPP? It is that ministry. That is how agricultural production has expanded greatly. They have mistakes but they are doing good work and they will be able to improve.”

Couched in politics

Museveni soon made clear the fact that the move was political, accusing UCDA of giving seedlings to only Opposition supporters.

“The other time when we were having our little battle in Parliament over abanyunyusi (parasites) of UCDA. Ababbi abo (those thieves). They have been stealing. Now my MPs say UCDA has been giving Opposition lawmakers seedlings and denying them to the NRM people. That’s why the Opposition was supporting UCDA.”

Coffee growing in Buganda dates way back. Richard Reid, in his book titled Political Power in Precolonial Buganda, says by the time British explorer John Speke was in Buganda, Buddu County was already a major coffee producer. Reid further reveals that when Speke arrived in Masaka, the district capital of Buddu, he observed that coffee grew in great profusion all over its land in large bushy trees with the berries sticking on the branches like clusters of holly-berries.

“Indigenous coffee had probably been grown in the region for several centuries. The berry was known locally as Emmwanyi and was classified as Robusta in 1898,” Reid writes, adding that the antiquity of the crop is hinted at, if not with any great accuracy, by the tradition that it was a member of the Enynonyi clan, which originally came with Kintu to be the latter's “coffee cook.”

Reid says before the advent of colonialists, coffee was rarely made into a drink. It was normally chewed after being dried in the sun.

“Throughout the lake region, coffee berries played a ceremonial role, being offered to guests as part of an elaborate process indigenous to Buganda, Tooro, Ankole and Bunyoro. Buddu was probably Buganda's most coffee-rich Ssaza (county), suggesting, as with certain types of plantain, that coffee became even more widely available during the second half of the 18th Century,” Reid writes.

Frederick Lugard, a British colonial administrator, also supported Reid’s claims, saying coffee was cultivated with little care in Buddu and that it was also cultivated on several islands by the 19th Century. Indeed the story of the crop would tell us much about the history of relations between the islands and the mainland.

What the British ended, in 1894, was the casual growing of coffee when they crafted a plan to join and combine the region’s communities, chiefdoms and kingdoms into a single governable state, ultimately leading to the creation of the nation of Uganda.

Mr John Lakony, a farmer in Pamin Yai Sub-county, Nwoya District, in his coffee garden on Monday. Several farmers in Acholi Sub-region have embraced agroecology to avert the adverse impacts of climate change. PHOTO/EMMY DANIEL OJARA

The British commoditised coffee by discouraging the habit of chewing coffee beans. They impressed upon locals the benefits of making the coffee soluble and summarily drinking it. Over time, the indoctrination bore fruits, with coffee transitioning into a cash crop after losing its cultural worth. With that, the colonial government facilitated the establishment of several large-scale Robusta coffee estates in Buganda, and, accordingly, introduced Arabica coffee varieties from Ethiopia and Malawi.

By the time the British rule ended, coffee was a key cog in Uganda’s economy to the extent that it created friction between the Buganda Kingdom and the Obote I administration. The pressure started to pile up within the Mengo establishment when Samuel Ssemakula, a representative from Mawokota County in the Lukiiko (Ganda parliament), came up with a no-vote of confidence motion against Katikkiro Michael Kintu. Inter-alia, Ssemakula accused Katikkiro Kintu of surrendering Buganda’s coffee to the Obote I administration. This, he added, had the effect of watering down Buganda’s federal status.

In his paper titled The Buganda Crisis of 1964, Ian Hancock says Ssemakula and Lukiiko members from at least the end of 1963 had lost confidence in Katikkiro Kintu. They cited Buganda's place within Uganda, and most importantly the low return on coffee. Yet this discontentment was perhaps misdirected since the central government was in charge of fixing coffee prices; not Mengo.

“The Kabaka's government did not fix the coffee grower's price; this was a matter initially for the Coffee Marketing Board, and the Uganda government. Yet in one sense, it did not matter whether Kintu was to blame or not. What did matter was that the Kintu government was held responsible for a host of real and imagined grievances. Kintu himself had become the target for pent-up frustrations and, later in the year, was to be the victim of their release,” Hancock writes, adding: “Kintu's government did not learn a thing from the events of early 1964. The appeal to loyalty had served its purpose and the government acted as if its decisions, and indecisions, had received a resounding vote of confidence. After all, if the government could survive the Ndaiga report, then surely it could survive anything. On the other hand, survival also depended on the loyalty of the Ssaza chiefs and this, in turn, depended on Kintu’s ability to secure what they believed were Buganda's interests.

The chiefs, and the Lukiiko and the Baganda Kingdom as a whole couldn’t be expected to support an administration which had demonstrably failed to protect Buganda’s throne, institutions and territorial integrity. By November 1964, it was clear Kintu had indeed failed. By then, the weakness and incompetence of his administration had become more than most Baganda could tolerate and Kintu was thrown out of office.”