Prime

Why Watoto church stalemate runs deep

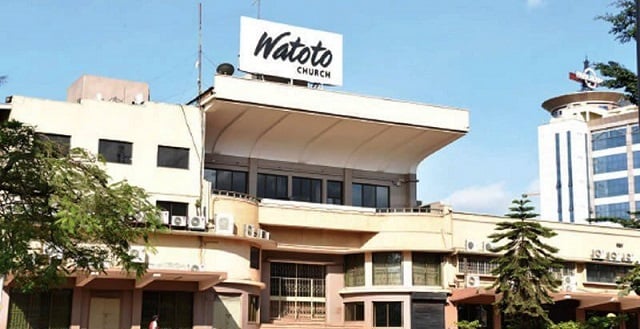

An artistic impression of the proposed new Watoto Church building. Photo/Courtesy of Symbion Uganda Limited/CCFU

What you need to know:

- Historic buildings in Uganda keep finding themselves in a bind. In this explainer, Bamuturaki Musinguzi outlines why it is important for the grip to be loosened.

- While the arts and culture used the building extensively, Odida allowed Pastor Gary Mark Skinner, the founder of Watoto Ministries, to sublet the cinema space for weekend church services, starting with Easter Sunday of 1984.

Why is there so much emotional attachment to the building that houses Watoto Church’s downtown campus?

The building that went up anywhere between the late 1940s and early 1950s housed Uganda’s first-ever cinema hall. An avant-garde architectural gem located in the heart of Kampala City, Norman Cinema was the handiwork of Norman Godinho.

The Goan entrepreneur came to Uganda in 1906, and built a reputation of being something of a property developer. Speke Hotel and Norman Godinho School (now Buganda Road Primary School) have his signature, as does the Norman Cinema building where cinemascope films from India and England were screened during the late colonial period.

Following the expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972, the Norman Cinema building fell into the hands of Hajj Edris Kasule.

He was an avid supporter of Idi Amin, so much so that the building’s ownership changed when Uganda’s third president was toppled in 1979. Francis Odida took over the building through political patronage.

While the arts and culture used the building extensively, Odida allowed Pastor Gary Mark Skinner, the founder of Watoto Ministries, to sublet the cinema space for weekend church services, starting with Easter Sunday of 1984.

Odida later gave the building to the church at no cost.

What makes the Watoto Church building so unique?

Dr Mark R O Olweny, an architect and urban designer, currently a senior lecturer of architecture at the School of Architecture and the Built Environment, University of Lincoln, says: “The value of the former Norman Cinema building is in its detailing, evident in its prominent horizontal sun-shading devices and elegant curves that define the street corner, curving around Kampala Road and up along Kyagwe Road, and finally into Buganda Road.”

He also notes that “the horizontal windows on the upper floors are juxtaposed with the saw tooth canopy, which acknowledges the changing levels along Kyagwe Road.”

Even more priceless per Dr Olweny is “the prominent curved entrance canopy that defines the entrance and invites visitors into the building via a grand staircase.” The building is largely intact with its main foyer oozing elegance and exterior “proudly advertis[ing] its role as a social and cultural hub in early post-colonial Kampala.”

“This is where its value as an architectural gem is derived,” Dr Olweny said of the state of the building, adding that “its prominence at a significant intersection act[s] as an important landmark for all.”

What does Watoto want to do to the building?

The church commissioned Symbion Uganda Limited in 2018 to design what came to be called the Watoto downtown mixed use development plan. This would ultimately see the old building demolished to pave way for a new structure on Plots 89 and 87 Kampala Road and plots 28, 30, 32, 34 and 36 Buganda Road, covering an approximate area of 0.866 hectares.

According to Symbion, a multinational architectural firm, the mixed-use development features a conference centre to seat more than 2,100 people, ample institutional space, youth-related functions space, retail space, and a three-star hotel with all functions for business and recreation.

After conservationists protested the proposed 12-storey building on account that it would upset the unique architectural history of the building, Watoto made a few tweaks.

In 2019, it submitted a redevelopment plan to Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) for approval.

KCCA declined to approve the designs, demanding that the developers submit a plan that caters to the preservation of some aspects of the historical building.

KCCA claims the building is a national heritage site and that the mixed-use plan would destroy a structure that has features of cultural importance.

Watoto was met with the same technical advice when it petitioned the National Physical Planning Board (NPPB). Left with little choice, the church sought legal redress in the High Court in 2022.

In the suit through ALP Advocates, the church contended that KCCA and NPPB refused to approve its proposed building structure yet they submitted revised plans for the same.

The church claimed that the decisions by KCCA and NPPB were irrational, illegal and unfair.

The church sought a court order to quash the decision by KCCA and NPPB and compel them to approve its plan. It also sought general damages for inconvenience and costs of the suit.

The current Watoto Church building. Photo/Courtesy of Symbion Uganda Limited/CCFU

What was the verdict?

On July 7, Justice Douglas Singiza of the Civil Division ordered KCCA to consider the church’s mixed-use development plan.

“The decision to reject the plan of Watoto Church and Kampala Playhouse by KCCA and the National Planning Authority Board is reviewed and set aside on account that the decision was procedurally illegal and improper,” Justice Singiza ruled before ordering KCCA officials to fulfil their mandate of approving the building plan within three months from the date the ruling was delivered.

He added: “In complying with this order, the respondents are at liberty to consider the existing KCCA physical development planning regulations and guidelines. In future, should KCCA wish to declare any property within its geographical limits a national heritage, a by-law should first be enacted to give it effect.”

Justice Singiza also ruled that KCCA should enact a by-law within three years to list all properties in Kampala that deserve protection as national heritage sites if it wishes to declare any property as such.

Will a statutory instrument right a number of wrongs as Justice Singiza suggests?

Mr Fredrick Nsibambi, the deputy executive director of the Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda (CCFU), agrees that the lack of specific statutory instruments and by-laws complicates “efforts to safeguard our important historical buildings, especially in urban areas.”

Monitor has learnt that the Attorney General’s (AG) office is finalising the statutory instrument that will operationalise the Museums and Monuments Act, 2023, which President Museveni assented to on April 27. The new law repelled the Historical Monuments Act, Cap. 46 and for related matters.

The Museums and Monuments Act, 2023, seeks to protect cultural and natural heritage resources and the environment, strengthen and provide institutional structure for effective management of the museums and monuments, prohibit illicit trafficking of protected objects, and promote local content of cultural and natural heritage.

The statutory instrument will operationalise Sections 93 (Application of the Mining and Minerals Act, 2022), and 95 (Regulations) of the Museums and Monuments Act, 2023.

A list of historical sites (including historic buildings) and monuments that will be protected, preserved and managed at a national level under the new law is also being finalised.

“The office of the AG is drafting the statutory instrument, hopefully in the next two weeks, they will complete and we shall invite stakeholders to give their suggestions,” Ms Jackline Nyiracyiza Besigye, the acting commissioner for museums and monuments in the Department of Museums and Monuments at the Tourism ministry, said.

She added: “The statutory instrument is not only for historical buildings, but for selected sites with national significance. Others include archaeological, paleontological, burial sites, to mention but a few. The list verified so far has about 250 sites. After gazetting the statutory instrument, we shall continue sensitising the owners of the sites, especially the historical buildings, on the significance and benefits they can get from these sites if preserved. For instance, we applaud Semei Kakungulu’s family, and Sir Apollo Kaggwa’s family, who have preserved their grandparents’ heritage (buildings) for posterity.”

What is the importance of preserving historic buildings?

Dr Mark R O Olweny, an architect and urban designer, currently a senior lecturer of architecture at the School of Architecture and the Built Environment, University of Lincoln, says historic buildings are part of a country’s cultural archive.

They are, he adds, an accumulation of artefacts that define “who and what we are as a society.” The need to protect, conserve, or preserve historic buildings is, therefore, derived from the understanding that these buildings provide tangible evidence of history, and of all the achievements of previous generations.

“We recall the Independence Arch at the entrance to the Uganda Parliament Building, a reminder of Uganda’s independence in 1962, or the Uganda International Conference Centre (now the Serena Conference Centre) built to host the Organisation of African Unity Heads of State meeting in 1971, a technically complex project completed in six months by Energoprojekt of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, or the grand Kasubi Tombs, the best-known example of traditional architecture in Uganda,” Dr Olweny opines.

He adds: “While monetary gain is something we all strive for, a key question we can ask is whether it should be achieved at the expense of what we regard as significant to our society. I use an analogy of the home. Would we be comfortable destroying all our parents’ and grandparents’ heirlooms simply because we have new crockery, cutlery, and furniture? However, we are happy to demolish the collective heirlooms of Uganda and East Africa, erasing what defines us as a society and the elements that drive tourism—heritage.”

Dr Olweny says a mindset change engineered and buttressed by education is of the essence.

“History [in schools] is presented as a series of stories without any real backdrop to the sites, monuments and architecture that form the tangible evidence of these stories,” he reasons, adding, “The lack of tangibility in our appreciation of what makes our society becomes a major threat to the conservation of historic buildings.”