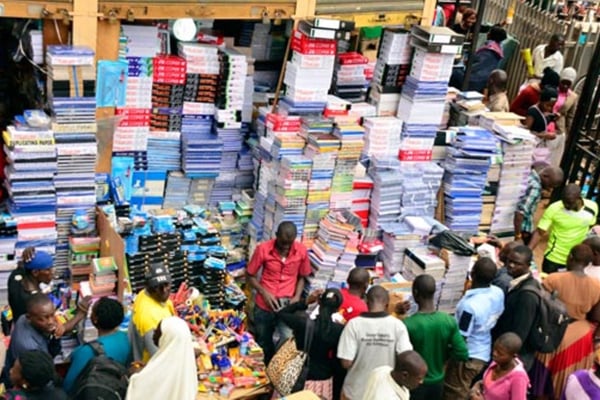

Traders and customers in Kikuubo, Kampala. Local businesses are vulnerable to unfair practices by powerful multinationals.

Photo | File

Knowledge and institutional gaps litter Uganda’s way as it prepares to put into effect its competition law without a statutory regulator, a situation that experts warn will hold the country hostage to multinationals that use their power to outcompete rivals using practices that might also keep local supplier firms stunted.

The fears arise out of a plethora of consumer protection issues and anti-competition practices. These happen mainly because, unlike other East Africa economies, Uganda has only just passed its Competition Act. The law, however, does not provide for an independent authority to regulate the marketplace.

Mr Joel Basoga, the senior associate at H&G Advocates, says Uganda has taken an unconventional approach by designating an executive governmental department as the enforcement authority, instead of creating an independent and dedicated Authority as most competition law regimes do for this purpose.

In Kenya, the Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) performs such a role while Tanzania has the Fair Competition Commission (FCC), and Rwanda with the Rwanda Inspectorate, Competition and Consumer Protection Authority.

Mr Sam Watasa, the executive director of Uganda Consumer Protection Association (UCPA), argues that due to Uganda lacking an independent regulator, small and medium enterprises have often collapsed as they struggle to supply multinationals which use unorthodox competition practices. Experts say this is common in the retail segment, where big supermarket chains and franchises use buyer power to tie-up their suppliers’ operating capital for months, often rendering them incapable of re-injecting proceeds in the business to increase output and supplying more supermarkets.

Anti-trust laws

Indeed, Dr Willard Mwemba, the chief executive officer of Comesa Competition Commission, also argues that companies often engage in unethical and unorthodox competition practices. They do this by often using their market power and dominance to fail rivals in the absence of a competent watchdog.

“Market power by firms is not illegal but use of that power to eliminate competition is wrong,” he said during the launch last month of a training initiative that is intended to give Ugandans the tools to navigate the competition law and consumer protection.

For instance, in December 2023, the CAK hit the local Carrefour supermarket franchise with a $7.1 million fine for abuse of buyer power, forcing suppliers to accept lower prices after the firm was found guilty of abusing its superior bargaining position with two contractors Woodlands Company Ltd and Pwani Oils Limited.

Another Kenyan firm, Orchards Ltd, which supplied yoghurt, also filed a complaint before CAK, which found Carrefour guilty of buyer power abuse and exploitation, which the franchise holder appealed and lost last week.

Mr Watasa says the Kenya Carrefour franchise lesson is instructive for the Ugandan retail sector.

“Abuse of buyer power is happening in Uganda,” he said. “These supermarkets will give you a contract to supply eggs but tell you ‘we will pay you after six months.’ Now imagine what happens to this small poor supplier who doesn’t even have capital to supply for two months.”

Notoriety of franchises

Mr Geoffrey Sserugga Matovu, the marketing manager of Sumz, a food company that produces a variety of packed snacks, says franchise holders are the most notorious customers and abusers of buyer power, who never honour the supply contracts or entertain complaints over outstanding demand notices.

“We are in catch-22,” he says. “We need them for visibility of our products on the shelves because they are big. But they don’t pay in 45 days as per contract, and if you are lucky, they may pay you after 90 days, which is also rare. Foreign supermarkets are the worst abusers.”

Under Uganda’s law, the Trade ministry is the designated administrator of the Competition Act, with the power to investigate anti-competitive practices and to specifically hear and determine complaints in respect to competition and consumer protection matters.

“Practically, this presents a challenge to the ability of the ministry as a part of government, to hear competition complaints against government entities or entities in which the Government of Uganda has a stake,” says Mr Basoga.

He adds that an independent authority allows the harnessing of expertise and enables competition advocacy within a country, but is also a good safeguard to put the government in check, if the state is engaging in acts that impair competition in the economy.

For instance, in April, the government tabled a proposal to invest Shs578.4 billion, which was approved by Parliament, for the construction of a pharmaceutical factory owned by DEI Pharma Limited, a private company in which the state plans to acquire equity. However, as the paperwork for government’s equity in the pharmaceutical company is not yet complete, experts say this is engaging in anti-competition as it stifles competition with players in the same line of business that invest borrowed money.

Without an independent watchdog, the government department meant to regulate competition becomes a co-opted actor in the controversial private businesses into which the state has invested billions of shillings, such as Atiak Sugar Factory and the International Specialised Hospital Lubowa.

Knowledge gaps

Lawyer Pheona Wall says unethical and anti-competition practices continue to happen due to knowledge gaps that exist in the market, among consumers but also among the elite, including Parliament, leading to loss of rights when multinationals acquire local companies.

“As we see regionalisation, and now the African Free Continental Free Trade Area, if we don’t have these institutions [to regulate competition] we will continue to see Western companies coming here and just taking over,” she says.

Competition act

In September 2023, Parliament passed the Competition Act 2023—which the President signed into law in February this year—to regulate anti-competitive practices and agreements, abuse of dominant position, mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures that might have an adverse effect on competition.

Initially, Uganda Parliament passed the Competition Act that proposed the creation of an independent regulator within the law, whose Clause 4 sought to establish the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission, and this resulted in a back and forth exercise between the legislators and the President.

President Museveni declined to sign the law and returned it to Parliament, stating that Clause 4 of the Act as passed, attracts a charge on the consolidated fund, at a time when the government was trying to cut back public expenditure by scaling down the number of taxpayer-funded state agencies.

However, Parliament’s Committee on Trade, which scrutinised and handled the Bill, says the lawmakers benchmarked Kenya, South Africa and Zambia, and their unanimous recommendation was to create an independent authority to regulate competition.

“The only setback was the ongoing rationalisation of agencies,” a member of the Committee said. “We refused and sent it back to the floor, saying that this proposed Authority must be maintained because it can fund itself. But this was not to be.”