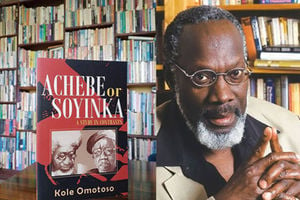

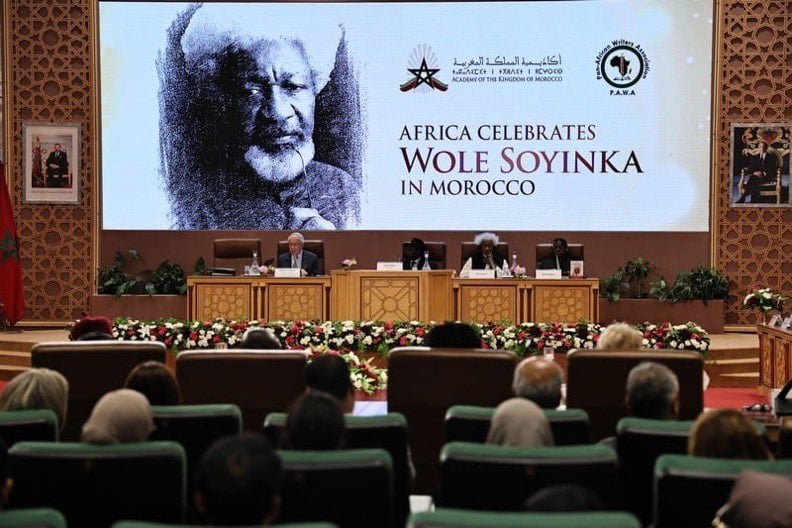

A panel during celebrations of Wole Soyinka’s outstanding achievements in both African and global literature at the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco in Rabat, Morocco, on Tuesday. PHOTO / COURTESY

At 90, Wole Soyinka, a renowned Nigerian playwright, novelist, poet, and essayist, shows no signs of slowing down. During a symposium staged at the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco in Rabat, Soyinka revealed the two motives that drive his creative process.

“I recognised the fact that there is a propelling axis both of history, relationships, vision, productivity, and even the understanding and recognition of other human entities,” he said of his first move, adding: “This is simply what I describe as the axis of power and freedom. In other words, power at one end and the other freedom. No matter what the ideology is, whether secular or theocratic, whether considered progressive or reactionary.”

Still full of energy, vitality and wit, Soyinka’s latest work—the 2021 novel titled Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth—is a satirical take that critiques societal issues and ills. During the symposium held in Rabat four days before his birthday on July 13, Soyinka revealed that he “came to understand quite early before I could articulate it that there is one propelling axis which revolves.” He further noted that “the world itself, humanity itself, revolves around the polarities between freedom and power.” He added that we are “obliged to choose” either. He chose freedom, “and if I can claim credit for any consistency is that I have stuck with the polarity.”

The notable works of the acclaimed writer, such as A Dance of the Forests (1966) and Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), explore themes of tradition, modernity, and the complexities of human existence.

“Nothing that I have experienced either in my own life or read in history or absorbed through creative words in any form, nothing has occurred of sufficient weight of analysis of understanding and even intuition to make me change that polarisation,” he said at the roundtable discussion dubbed “Africa Celebrates Wole Soyinka” in Morocco.

Soyinka, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, has long been revered for his poignant and powerful works, which often explore themes of oppression, justice, and human dignity. The second motive for his creative works, he told an attentive audience, that cultural figures, academics, and diplomats, occurred nearly two decades ago when something unusual was discovered in his native Nigeria.

The commemorative event, organised by the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco in collaboration with the Pan African Writers Association (PAWA), celebrated the Nigerian writer’s outstanding achievements in both African and global literature.

The Permanent Secretary of the Royal Academy, Abdeljalil Lahjomri presented Soyinka with the shield of the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco.

Lahjomri lauded Soyinka’s unwavering dedication to portraying African realities in an interview with the local press.

He described Soyinka as a “defender of African cultures” and a keen observer of the continent’s complexities.

Lahjomri stated that Soyinka’s refusal to align with the Negritude movement, emphasizing his ongoing battle against all types of domination.

“Unusual, I use that ironically because for me, there was absolutely nothing unusual of the discovery or the encounter more accurately of any other human beings. What happened in the Middle Belt of Nigeria was that a ‘tribe’ was discovered, which somehow had escaped, do we say, the modernisation ‘progressive’ advance of society. I forget the name now,” he noted.

Adding of the community he referenced in his latest prose work, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, thus: “That rudimentary society, for me, produced its own forms of existence and continued to survive, despite everything going around that isolated portion of the Middle Belt of Nigeria. They remained and retained one thing that tied them to the rest of society wherever on the globe and that is their humanity.”

Commonality of humans

At the symposium, Soyinka’s steadfast dedication to social justice and his unwavering commitment and distinctive advocacy for African cultures was celebrated. When he spoke, it was easy to see why.

“Between that ‘primitive’ or shall we say an advanced citizen of that little community […] and the most sophisticated, most celebrated astronaut or rocket scientist, to use the commonest expression, there is absolutely no difference,” he said of the community in the Middle Belt of Nigeria, adding: “They are bound together by that common factor, that essence that we call humanity. And that, for me, is the basis of community, of society, of state anywhere in the world. And that it is almost blasphemous to consider one superior to the other simply because of certain advances either in what we call the humanities or more sophisticated architecture, painting, music, etcetera.”

To round things up, Soyinka said while he admires astronauts so dearly, it is not lost upon him that “the guiding philosophy, or shall we say enabling principle of my existence and my creativity, [is] a recognition of the commonality of all human beings wherever and at whatever age.” Soyinka, therefore, argues that if you pluck an individual from that so-called primitive society environment and you put them in the company of astronauts, the aptitude of the former will always be tangible.

“This, for me, has always been my interpretation of historical events, and so-called technological advancements. And it runs parallel to that understanding of the polarity between power and freedom. In other words, we live in a world where there is always a tendency towards domination using whatever excuses that happen to be available,” he said, adding that this could be “because one side follows a spiritual construct that we consider advanced over other spiritual constructs, which enables us to look down on religions which we are encountering for the first time, however, ancient.”

Celebrated

Before defining what he colourfully called “the scaffolding of my work whether as playwright, as poet, as essayist, satirist, and even as failed musician, failed architect, and failed astronaut”, Soyinka was celebrated in every sense of the word. Ali Benmakhlouf, a member of the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco, said literature and life are intricately woven in the very structure of Soyinka’s writings, of his life, the life of African people. Benmakhlouf noted that Soyinka rejects the fallacy of misplaced struggle and pays attention to history, to the dreadful affinity between new independent governments and colonialists.

Soyinka’s theatre claimed for justice in the open spaces. He was creating a public space with his plays; not just creating plays in a public space, Benmakhlouf reasoned.

Theatre, unlike other fields of literature, gives its audience not only words to listen to, but also images, songs, different idioms, actions. So the stage is a “social vehicle” and theatre is “a tactile process” that impacts most people quite easily.

You, yourself feel, alive when your printed words are brought out on stage,” he said, adding: “Through an African’s eye and mind, Wole Soyinka describes more than the African life. He describes and encourages the sources of self-regard in all human beings. Chronicles of the Happiest People on Earth was a novel he wrote for meeting an ‘internal demand.’ He wanted to expunge something that was coming to a collective boil, that is to say, to tell the truth in a harsh way about the Nigerian society, about all the wrongs done to people, about all these people separated from others because of their rich position, and thinking they can be okay with that.”

A new poetry collection titled Wole Soyinka: A Bilingual Collection of Poems and Essays, edited by Prof Bill F Ndi, was launched at the event. The anthology of 74 poems in English and 12 poems in French, by poets from Africa and beyond, is dissimilar in commissioning and processing, yet similar in profundity.

The poems profile Soyinka’s biography in limitless space and time vortex. Herein, Soyinka’s shape shifts into spaces between galaxies and time zones in thought and spirit. The 90 years of Soyinka’s existence on earth are considered by the 86 poems as gestation and labour of millennia of human existence beyond its endometrium.

Who is Soyinka?

Soyinka is considered by some to be Africa’s finest playwright. He studied in Nigerian schools and the University of Ibadan before going to Leeds, England.

He gained professional experience as a playwright at the Royal Court Theatre in London.

After returning to Nigeria in 1960, he led attempts to develop Nigerian theatre while studying and researching at the universities of Ife and Ibadan until he was imprisoned after the outbreak of the Nigerian Civil War. He described his experiences in his novel, The Man Is Dead.

His plays have been performed in Africa, Europe and America, including The Road, and The Lion and the Jewel.

He has also published four collections of poetry. His second novel was published in 1973. He currently teaches at the American University in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Soyinka wrote his first plays during his time in London, The Swamp Dweller, and The Lion and the Jewel that were both published in 1963.

Others are The Trial of Brother Jero (1963) with its sequel, Jero’s Metamorphosis (1973), A Dance of the Forests (1963), Kongi’s Harvest (1967), Madmen and Specialists (1971), The Strong Breed (1963), The Road (1965), Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), Opera Wonyosi (1981), A Play of Giants (1984), and Requiem for a Futurologist (1985), among others.

His other two novels are The Interpreters (1965), and Season of Anomy (1973). Purely autobiographical are The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972) and the account of his childhood, Aké (1981).

Soyinka’s poems are collected in Idanre, and Other Poems (1967), Poems from Prison (1969), A Shuttle in the Crypt (1972), the long poem Ogun Abibiman (1976) and Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988).

His literary essays are collected in, among others, Myth, Literature and the African World (1975).

In conferring the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986 to Soyinka, the Swedish Academy said: “who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.”

“…Soyinka writes in English, but his works are rooted in his native Nigeria and the Yoruba culture, with its legends, tales, and traditions. His writing also includes influences from Western traditions—from classical tragedies to modernist drama,” the Swedish Academy added.

Soyinka was twice jailed in Nigeria for his criticism of the Nigerian government, and he destroyed his US Green Card in 2016 when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States.